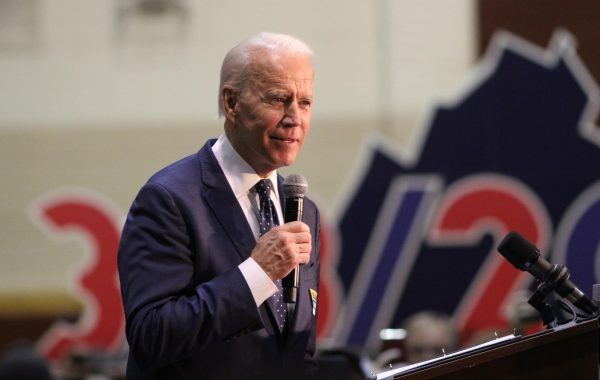

Dr. Leonard Moore: Studying Black history an excellent way for students to increase their cultural intelligence

Veteran UT history professor gives Knights a taste of his popular course, ‘Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow’

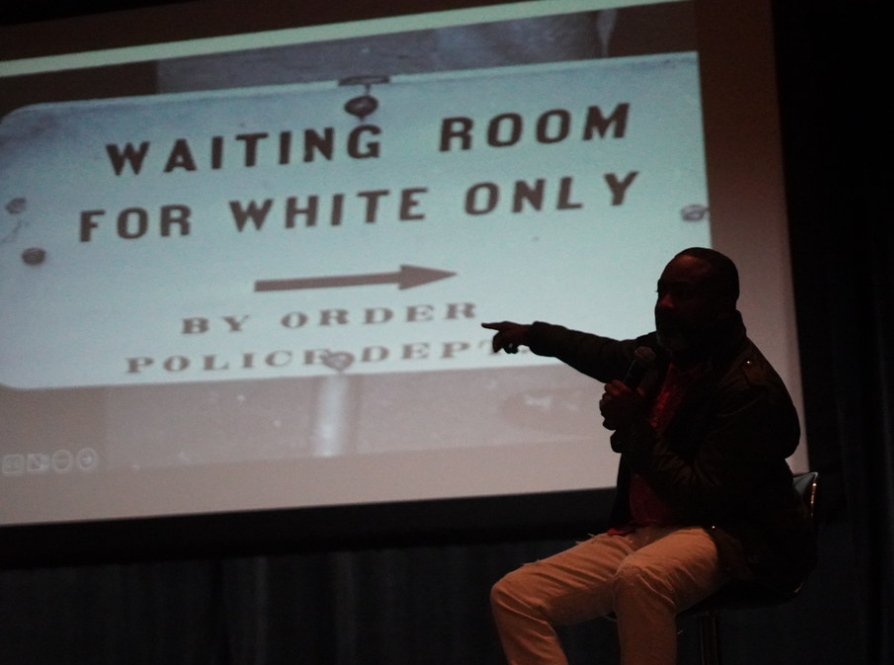

In one memorable portion of his presentation, UT history professor Dr. Leonard Moore likened the economic legacy of this discrimination to a messed up version of Monopoly where he (representing a Black southerner) plays a board game with white neighbors in which he was not allowed to buy anything until after going around the board 20 times.

March 1, 2023

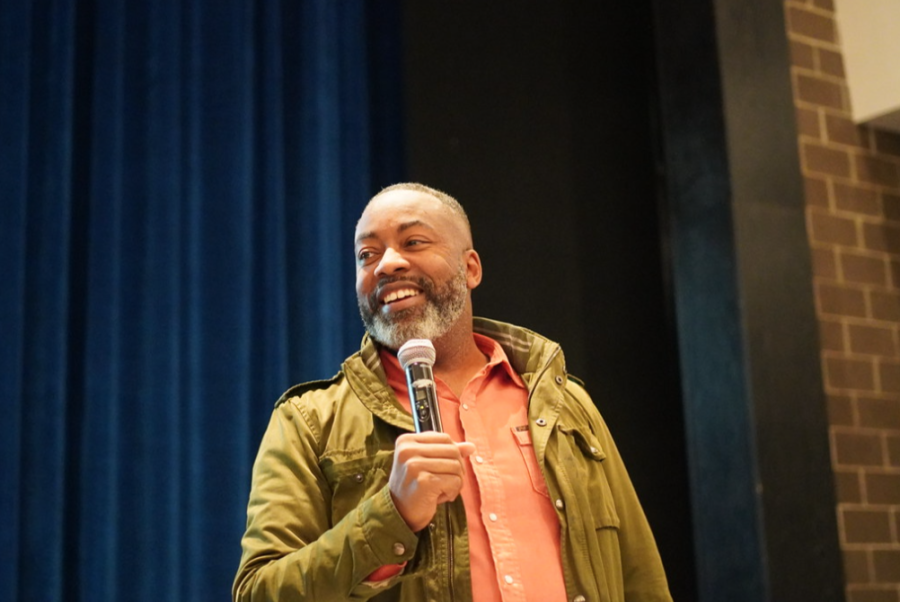

As he has for many years, UT professor Dr. Leonard Moore helped McCallum commemorate Black History Month on Monday Feb. 13 with three lectures in the MAC that gave the students in attendance a taste of what UT students learn in Moore’s popular American history course, “Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow.”

In a presentation that he gave to students during first, second and fourth periods, Moore connected the past and the present and stressed above all the importance of increasing one’s cultural intelligence by learning about the perspectives and experiences of people from different backgrounds.

Black history’s essential. It’s essential. I don’t think you can function without knowing it.

— Dr. Leonard Moore, UT history professor

“I think that Black history’s essential. It’s essential,” Moore told MacJournalism after his first-period lecture. “I don’t think you can function without knowing it.”

He said that the more than 300 white students taking his UT course understand this and sign up for the course so that they are equipped to thrive in a diverse, modern workplace.

“I love teaching white kids Black history,” said Moore, who is in his 16th year as a professor at UT after nine before that at LSU. “They love it, they eat it up. I just wish moms and dads of younger kids would see the value in getting their kids exposed to Black history at a younger age.”

Before he began his lesson about the Black southern experience in the post-Civil War south, he asked the students if they wanted to hear the collegiate version or the high school version of the presentation. After the group responded that they wanted the collegiate experience, he spoke at length about the past and the present and how they are inextricably connected.

“The past is never the past,” he told the students. “The present is the product of what happened before.”

Moore said that the southern Black response to earning their freedom in the wake of the Civil War reveals that Black people valued innovation, entrepreneurism, family and education. After earning their freedom, Black southerners left the plantation, changed their names, reunited their families, purchased property, started their first public schools in the South and created their own churches. In response to these initiatives, the white southern power structure enacted Jim Crow segregation and disenfranchised Black voters through a mix of direct violence, poll taxes and grandfather clauses.

In one memorable portion of his presentation, Moore likened the economic legacy of this discrimination to a messed up version of Monopoly where he (representing a Black southerner) plays a board game with white neighbors in which he was not allowed to buy anything until after going around the board 20 times. By then he said, he would not be able to buy any property because the white players would have bought everything on the board before he was allowed to play equally.

To extend the analogy, Moore encouraged the students to imagine the parents leaving the house and their children coming downstairs to continue the game they inherited from their parents. Taking his place at the board, Moore’s daughter would have no property and no money because he would have nothing to leave to her, and the other players would have the resources they inherited from their parents. The analogy, he said, describes what happened to the generations of Black families who lacked resources to use to build wealth across several generations.

The Black woman is the most disrespected person on the face of the Earth.

— Dr. Moore

While Moore argued that the present is inextricably affected by the past, he also offered some of his strongest criticism for current American culture, specifically Black male hip-hop artists who he said degrade Black women in their lyrics.

“The Black woman,” Moore said, “is the most disrespected person on the face of the Earth.”

He summed up his lecture by congratulating all of the students in attendance for increasing their cultural intelligence.

The Monday sessions were part of the MAC BACKS BLACK Black History Month celebration activities. Those events continued with lunchtime Movie Knights in the library where attendees watched episodes of the Golden Globe and NAACP-award winning series, “Blackish.”

There was also a cornrows and box braid demonstration during lunch in the center hallway on Feb. 17.

The following week, Mac celebrated HBCU Day. Students and teachers were encouraged to wear clothing to represent a historically Black college or university or any college or university. On Thursday of this week, there will be a student teen panel presentation in the MAC and the winner of the Black Girl Magic contest will be announced.

View this post on Instagram

![With the AISD rank and GPA discrepancies, some students had significant changes to their stats. College and career counselor Camille Nix worked with students to appeal their college decisions if they got rejected from schools depending on their previous stats before getting updated. Students worked with Nix to update schools on their new stats in order to fully get their appropriate decisions. “Those who already were accepted [won’t be affected], but it could factor in if a student appeals their initial decision,” Principal Andy Baxa said.](https://macshieldonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/53674616658_18d367e00f_o-600x338.jpg)

Ruby Magee • Apr 17, 2023 at 10:39 am

I liked this article because I attended this lecture and I think it was summarized very accurately and did a good job talking about the main points Dr. Leonard made.

Charlotte Cross • Mar 7, 2023 at 2:30 pm

I like how Dr. Leonard Moore said “The past is never the past, The present is the product of what happened before.” I’ve never heard someone say that before and hes completely right. I went to one of his presentations and his points were incredible. I thought i was going to hear stuff i have heard before but he gave me so many more perspectives and ideas about Black History. I love the pulled quotes in this story, well chosen.