Virtual education is best bad option

Despite how badly we want to be back on campus, resuming in-person schooling would be a mistake because it would spread a still-raging pandemic

McCallum senior Molly Gardner attends the class of 2020 drive-by graduation parade on May 28. The parade has been one of the few on-campus events that have taken place since COVID-19 prompted the closure of the campus on March 13. Photo by Evelyn Griffin.

August 16, 2020

Normally, 16th birthdays are defined by family, friends, and that ceremonial first drive with a newly minted driver’s license—a celebration akin to Molly Ringwald’s ride in Jake Ryan’s cherry-red Porsche and a cake adorned with 16 candles in the iconic ’80s film. But for so many Austin students (including us), the ongoing quarantine has rendered those birthday aspirations impossible to achieve. Instead, we’ve replaced such milestone moments of our youth with solitary serenades over Zoom, drive-by graduation parades, and FaceTime celebrations of the last day of school. From the look of it, experiencing high school, and life in general, through a computer screen is a reality we seem destined for in the coming months. But with the COVID-19 pandemic bearing down on our city and on our campuses, it’s the only choice we’ve got.

Thursday, March 12, was the last time we stepped on campus—our last chance to wave at friends in the halls, kill time at nearby Thunderbird Coffee, and congregate with the Shield staff. We spent the day preparing to cover upcoming events, including an important choir contest and a high-stakes baseball tournament. While that day stands out as the last remnant of normalcy in our lives, we believe digital distance learning is the only way to protect our families, our campuses, and our communities.

When we first learned that school was canceled the following morning, we had no idea what we were in for. With spring break slated to begin, the ensuing weeks felt like an unexpected gift: extra time to relax away from our busy schedules. Little did we know that our final day of school had come and gone unnoticed. After the district-mandated three-week sabbatical from classes, we began our journey into the strange new world of online learning.

Unsurprisingly, digital education provided its fair share of highs and lows. Because of how quickly our online programming was put together, teachers were often left to their own devices, which made workload and structure vary wildly from class to class. For example, some instructors required consistent completion of weekly assignments; others were uncommunicative online and rarely required work to be completed at all. There was even one class where we were only asked to finish two assignments by semester’s end to receive a passing grade. Other courses—complete with lecture videos, optional activities to improve proficiency, and one-on-one help through Zoom—provided a near-seamless transition to virtual learning. Regardless of our educators’ level of preparation, though, their efforts to adjust on the fly in the middle of a world-altering crisis was nothing short of admirable.

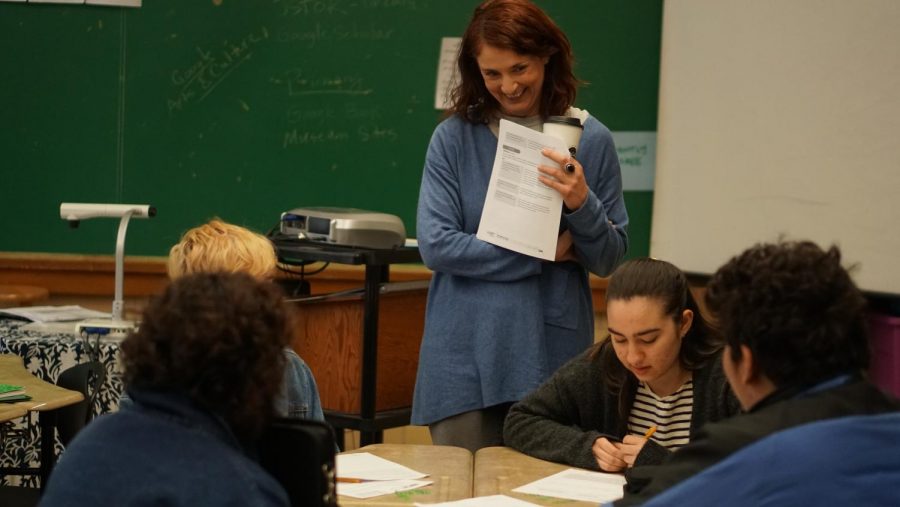

We’re hardly alone in this thinking. English teacher Nikki Northcutt says online learning last semester was an especially difficult venture for instructors because of how little time they had to prepare. “Since distance learning last semester was a stopgap measure, it was very rudimentary and stripped-down,” Northcutt told us. “I would describe my experience last spring as generally depressing. Everything I love about the classroom—group interaction, spontaneity, the momentary interplay between students and myself—was all stripped away… I just felt a massive drop in student engagement.”

Despite the at-times lackluster quality of education that online learning afforded us in the spring, it’s not the only reason we want to get back to our school. We long to return to eating lunch with friends next to the choir building and seeing what wacky meals our classmates will bring to English every day (we’re looking at you, Johan)—we even miss the not-so-fun stuff, like struggling through chemistry and stressing with friends over which Chinese dynasty did what in AP World History. The high school experience is about so much more than, well, school. It’s a chance to grow as a person—to learn valuable lessons and have unforgettable experiences that we will cherish for years to come. While we’ll dearly miss these things in the coming months, the safety and health of Austin’s students, faculty, and staff have to be the district’s top priority.

With that in mind, we simply can’t agree with the state and federal leaders who are pushing to open campuses up to start the school year. Over the past several months, President Trump and Education Secretary Betsy Devos have been especially eager to reopen schools for on-campus learning, even as coronavirus cases have spiked in cities across the country, including Austin. In a July 10 tweet, Trump even threatened to revoke federal funding from schools that don’t return to campus in the fall. Despite advocating for such drastic reopening efforts, the president (who only recently donned a face mask for the first time) has refused to support vital public health measures, including a mask mandate.

With such a bad example coming from the nationwide stage, it’s no wonder that Texas is so behind the curve on preventing COVID-19 transmission. Gov. Abbott, who has cultivated a close relationship with the president, followed suit by avoiding obvious safeguards like mandating masks and limiting business operations until Texas became the COVID-19 hotspot in America last month. This indifference has proven deadly for our state. Within two weeks of kickstarting the governor’s May 1 effort to reopen Texas, the state’s new cases per day skyrocketed from 593 to 1,843, according to Texas Health and Human Services.

Even as nearly 500,000 Texans have contracted COVID-19 and close to 8,000 have died, Abbott has remained staunchly committed to reopening the state as quickly as possible. “We have abundant supplies that we will be able to continue to provide PPE [protective personal equipment] to schools, to hospitals, to nursing homes, to testing sites, to any operation within the state of Texas that’s going to need PPE in response to the pandemic,” Abbott recently told reporters.

At Trump and Abbott’s recommendations, many schools across the country are currently planning to return to campus this month, at least in a partial capacity. The Texas Education Agency made this decision clear on July 7, when it announced its guidelines for the 2020-2021 school year that allow for either 100 percent in-person instruction, or 100 percent virtual classes. But with the fall semester rapidly approaching, many school districts (including AISD, which announced last week that classes won’t start until Sept. 8 and could remain online-only for weeks to come) have wisely issued delays of in-person instruction—a move that was bolstered by the Austin/Travis County Health Authority’s July 14 order requiring public and private schools to push back in-person instruction until after Sept. 7. (The order also banned extracurricular activities and sports from taking place until campuses reopen for in-person instruction.)

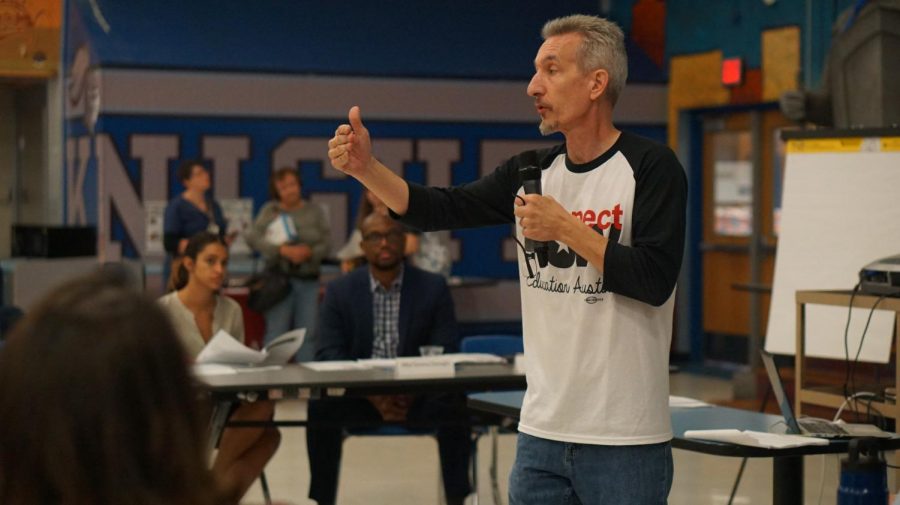

Pushing back the school year was the right move, but a far longer delay is needed to ensure the safety of students and staff alike. To that point, Education Austin, an AISD teacher’s union, is demanding that a nine-week virtual delay take place before the district returns to in-person instruction—and that’s only if COVID-19 case trends indicate that it’s safe to do so. We support these demands as students who are concerned about the health of ourselves, our peers, and our teachers. “If they wanted us to go back to school in the fall as if nothing was wrong, then maybe we should have implemented strict mask and social distancing guidelines in March,” says Robert Bucher, a McCallum history teacher and the school’s representative for Education Austin. “Truly, I want nothing more than to get back in the classroom, but I don’t want to see one colleague or student have their life ruined by this virus. Not one. Because for me, there is no acceptable amount.”

Local health experts agree. In July, Austin Public Health Interim Health Authority Dr. Mark Escott told KXAN that a return to campuses before a vaccine is available and schools have time to prepare to host students and staff would endanger the lives of everyone involved. Rushing a return wouldn’t just lead to up to 1,370 student deaths in Austin, Escott said: It could also kill faculty and staff at a rate of two to 10 times higher than kids. These numbers are jarring, and they underscore the fact that in-person instruction simply can’t take precedence over the lives of our city’s students, staff, and their families.

Sadly, without a vaccine and without the necessary time to ensure the social distancing and sanitation measures are established, these grave possibilities will become reality in Texas schools. What if one of these deaths happens at McCallum? Is it inevitable that the swift return to on-campus learning that AISD has planned will result in coronavirus infections at our school? If an especially vulnerable student catches the virus at school and dies, will our leaders care, or will that student become just another statistic? These aren’t questions 16-year-olds should have to ask themselves.

America’s youth deserves better than this. We aren’t pawns in a political game; We’re the future of this country. Now more than ever, we need our leaders to guide and protect us—because, right now, that future has never seemed more precarious.

This article originally appeared on the Austin Monthly website on Aug. 11.

![Education Austin president Ken Zarifis, shown here speaking during the AISD budget stabilization task force meeting on Nov. 7, 2018, demanded on Wednesday that TEA and Austin ISD offer wholly online classes at least for the first nine weeks of the 2020-2021 school year. “We have heard too much from the commissioner [and] from the governor that would lead us down the wrong path,” Zarifis said. “We believe that they do not have the interests of workers, of students and their families in mind as they make the decisions that seem to be more guided by fiscal realities than human realities.” Photo by Bella Russo.](https://macshieldonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/46478948361_91ce2d2f96_o-2-300x168.jpg)