Austin isn’t what it used to be, and even as high schoolers we have seen beloved places such as Dart Bowl, I Luv Video and Nau’s Drug Store go under. Austinites who have lived in Austin since the ’80s or ’90s have seen Austin nearly double in size. They have seen businesses come and leave, historical landmarks vanish, demographics change and average housing prices increase by nearly half a million dollars. For some, losing pieces of the city you love means your favorite coffee shop doesn’t exist anymore or the trail you used to walk your dog on is now an apartment complex, but others face a much more serious issue: gentrification and being driven out of their neighborhoods. The “Old Austin” we love was created largely by Black and Brown communities who are now being driven out of the city by increased rent and taxes on their already-owned homes.

Before delving into gentrification in Austin it’s important to acknowledge the role that many McCallum students and their families often play in causing (or being affected by) gentrification. The Urban Displacement Project characterizes the Brentwood neighborhood just north of McCallum as experiencing “continued loss gentrification.” Residents are not always aware that they play a role in pushing out minority communities when they support businesses that are gentrifying areas, thinking that they are just “hip new spots.” People who have moved into gentrified areas need to acknowledge their contributions to gentrification and their own privileges.

The eastern crescent is a geographical and demographic pattern forming a C and encircling central Austin. It begins north of downtown and follows U.S. Highway 183 toward south downtown. In the past 30 years, disadvantaged families in the eastern crescent have been displaced because of Austin’s rapid growth.

Currently in Austin, according to Bloomberg, 55% of people rent their homes, which is similar to the percentages found in other large cities. What is disproportionate is that 52% of white households own homes whereas only 29% of Black households and 35% of Hispanic households own their homes. This trend is something that’s seen in big cities across the nation. Owning a home means although your property taxes can rise with a changing city, you otherwise have a fixed monthly mortgage. Renting in a city with rising property rates means residents can be driven out of Austin quickly when rent costs spiral upward.

According to a study done by the University of Texas, out of the 200 Austin neighborhoods, 58 are affected by gentrification. Twenty-three of those neighborhoods are in the susceptible area meaning there are vulnerable populations, and the surrounding areas have rising property costs. Type 1 gentrification occurs when housing costs are beginning to rise, and 13 Austin neighborhoods are affected by this. Type 2, known as dynamic gentrification, involves rising housing costs but also changing demographics, and 12 neighborhoods are in this phase of more drastic gentrification. Finally, there are four neighborhoods in late stages of gentrification, and six categorized as a continued loss.

The “right to return” law was approved in 2018, allowing the city to sell property at a lower rate to long-term low-income residents who have been affected by gentrification. The law was delayed by the pandemic but was enacted in 2021. As of 2022, the city had 24 houses to sell, and application processes were complicated, with applicants needing to prove they had been affected by gentrification.

A private solution similar to this government solution is a community land trust where a non-profit owns a piece of land and uses it to provide affordable housing to those in need.

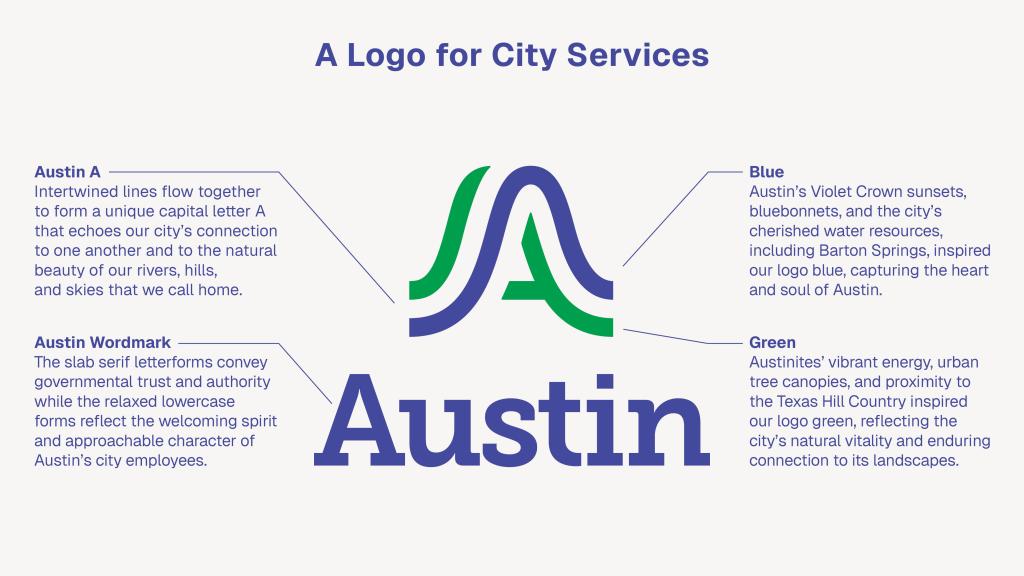

In the Austin mayoral race, both top candidates Celia Israel and Kirk Watson had housing plans to provide low-income housing for those affected by gentrification. Mayor Watson’s plan included developing many acres of land into a Mueller-like development for low-income housing. To preserve the city, it is crucial to support candidates who won’t sell out Austin in favor of development projects.

Although all of these policies are a good start, reopening minority-owned businesses and preventing further gentrification are also essential steps the city must take.

The neighborhoods affected by gentrification surround downtown and the UT campus. Family-run, Black and Brown-owned businesses have been run out of downtown because of gentrification, so when people say “Austin isn’t what it used to be” or “I miss the old Austin,” gentrification is to blame and Austin leadership needs to take drastic action to save the “Old Austin” before it’s too late.

Amaris Martinez • May 12, 2023 at 10:03 am

I like your article because it shows that Austin has changed so much, I am really ashamed that many stores have been closed or remolded into something diffrent its a very big deal do know its changed so much.

Evelyn Jenkins • Apr 16, 2023 at 6:56 pm

It’s really a shame that beloved Austin stores and businesses are being replaced. Even in my neighborhood cute one-story houses are being destroyed and replaced with three-story mini-mansions.

darby roldan • Apr 16, 2023 at 10:30 am

i like your article, because it showed me the effects of us as students, and i did not realize how much austin had changed, the real details until reading this. it is an eye opener but a very interesting topic since it is very relatable.

Eh • Apr 10, 2023 at 12:06 pm

I would love to go to Dart Bowl.

Eh • Apr 10, 2023 at 12:04 pm

I would love to go to Dart Bowl.