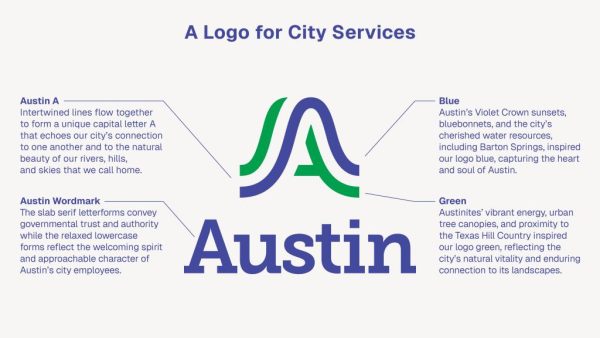

Hidden in plain sight

City leaders mislead Austinites about climate-related bills, which often make city more dense, worsen environmental impacts instead of alleviating emissions

Austin’s Net Zero plan seeks to create renewable energy solutions and eliminate carbon emissions through new infrastructure, but in reality these policies push for more urbanization and grant developers tax breaks.

Austin’s growth is inevitable.

Over the past decade it has consistently been ranked by publications such as U.S. News and World Report as one of the “best places to live.” It is home to many of the largest tech companies in the world, and it has enjoyed a booming economy that has seen a minimal impact to the current housing market’s downturn.

As a result, Austin is also one of the fastest-growing cities in the country. According to The Austin Business Journal, it averages 184 new residents a day.

But what shouldn’t be inevitable is the negative environmental impact that comes with this growth. More people means more buildings, more electricity usage and more trash.

Austin has attempted to combat this negative impact with Net Zero. This is an initiative that seeks to minimize carbon emissions by replacing current buildings with new more energy-efficient ones. These new buildings would use primarily renewable energy sources and would have updated accessories, such as faucets and heaters, that would allow them to minimize their energy expenditure. According to the city, Net Zero would completely eliminate Austin’s CO2 emissions by the year 2040.

But this plan is flawed. Building new infrastructure at the capacity and pace that the city claims is necessary to meet its goals would actually hurt, not help, the environment.

One of Net Zero’s first stages, nicknamed “CodeNEXT,” attempted to rewrite Austin’s land development code. If it had successfully gone through, CodeNEXT would have allowed skyrises and condos to be built within blocks of residential homes.

The initiative was scrapped in 2022 after a group of homeowners successfully sued the city on the grounds that they were not informed of the changes. Despite this, CodeNEXT poked a significant hole in the Net Zero plan.

For one thing, it showed the city’s true intentions.

The idea behind CodeNEXT was that it would provide developers with fewer restrictions when building housing and mixed-use developments if they were considered “energy efficient” by the city. But the very creation of these buildings would have done just the opposite.

According to a study conducted by Architecture 2030, 23% of global CO2 emissions come from the production and use of concrete, steel and aluminum, which also happen to be the three most common materials used in construction. Furthermore, according to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, demolition and construction account for 25% of the waste that ends up in U.S. landfills each year.

In other words, despite the city of Austin’s claim that Net Zero is intended to help the planet, in actuality, its first stages, would dramatically increase overall waste production and CO2 emissions.

That’s because Net Zero isn’t about the environment. It’s instead being used to hide policies such as CodeNEXT that will make the city denser and more populous, expanding the metropolitan area.

Texas doesn’t have a state income tax, the City of Austin gets the majority of its revenue from property taxes. More houses, especially new more expensive ones, would go a long way towards increasing the city’s financial coffers. City officials felt the need to hide these proposed land code use laws because the city’s current residents are the very ones who will be most affected by these changes.

CodeNEXT would have allowed houses that back up to commercial real estate, to have 85-foot buildings towering in their backyards.

This would not only drive out the residents in these homes but also outprice them.

The city justifies the creation of these new buildings with the claim that they provide “affordable housing,” a claim that is only somewhat true. Most cities have an anti-displacement plan, which is meant to prevent current residents from being outpriced of their homes. Austin’s anti-displacement plan, called “Project Connect,” focuses on creating a new metro system and developing its surrounding areas. It also includes an allocated $300 million in funds to create “more affordable housing.” The city plans to use this money to subsidize developers who build along the metro and put a certain percentage of the units aside for affordable housing.

The actual impact of this affordable housing, however, is negligible. In some cases, developers are granted significant tax breaks by setting aside as little as 10% of new units. Previous Austin land developments such as Mueller were created with similar subsidies. And while roughly 28% or 1,288 of their units are technically affordable housing, it’s set for families who make less than 60% of the Median Family Income (MFI). While this does provide some aid, it’s not to the extent to which the city needs it—currently, 52% of the current population makes less than 60% of the MFI.

Austin is a progressive city, and the legislature is well aware of this. That’s why they won’t hesitate to disguise their selfish agendas, as in the case of CodeNEXT, which was disguised as part of Net Zero, to appear as the forward-thinking initiatives that Austin voters want.

Austin, and its citizens, can make an impact on the environment for the better. The city needs to focus less on creating new infrastructure and more on upgrading, or “recycling” the buildings in place. This could look like adding solar panels, insulation or even new faucets to older homes.

In addition, Austin citizens need to be aware of the laws they are voting on. Without critical and independent thinking, the city’s environmental impact is going to continue to grow, and in the process displace a decent portion of the population.

Your donation will support the student journalists of McCallum High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.