‘Don’t Worry Darling,’ at least there’s Florence Pugh

Pugh steals screen throughout storytelling mess

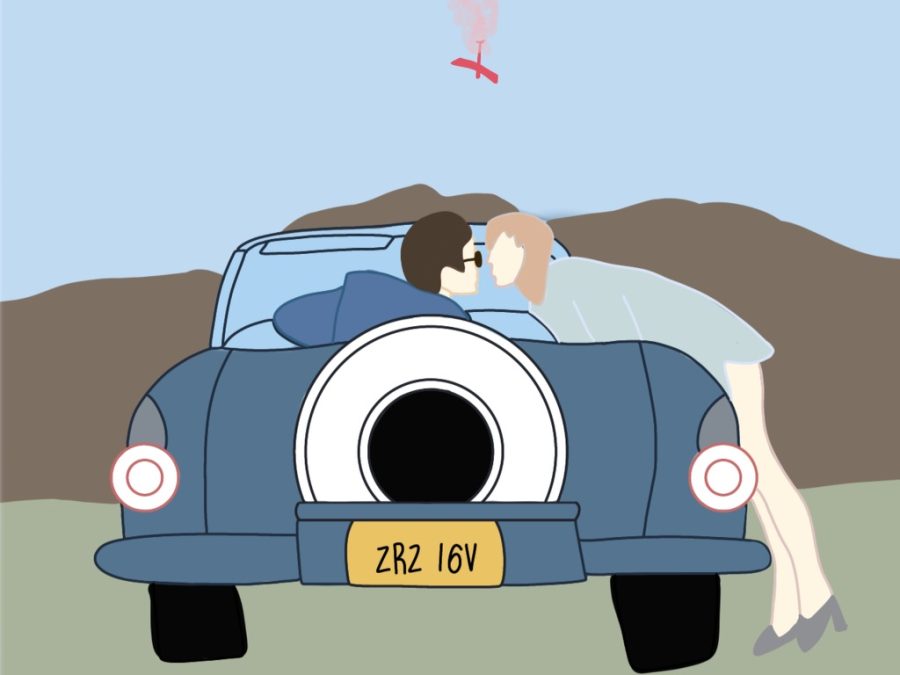

Alice Chambers (Florence Pugh) kisses her husband Jack (Harry Styles) goodbye as he heads for work at the Victory Project.

Warner Bros. UK & Ireland Youtube Channel

November 26, 2022

Alice Chambers and her husband Jack (Florence Pugh and Harry Styles) live in the idyllic suburban community of Victory filled with glossy mid-century modern homes and young, distractingly attractive families. Every morning, Alice waves her husband goodbye as he and the other men of the neighborhood make an ominously synchronized exit in their procession of pristine cars and head for work at the Victory Project, run by a charismatic cult-leader type person named Frank (Chris Pine), where they claim to be developing “progressive materials.” Alice’s days are filled with shopping, gossiping, household chores such as making dinner for her doting husband, the clink of martini glasses at lavish cocktail parties and steamy sex with Jack before he’s even taken a bite of her homemade roast.

The introduction of Margaret (Kiki Layne), a woman who Alice’s neighbors deem as having gone insane and who she eventually witnesses jump off her roof, provides her with an early clue (or can it even really be called a clue?) that something sinister lies under Victory’s carefully constructed facade of bliss. Alice increasingly begins to lose her grip on reality as she’s gaslit at every turn for her suspicions by her husband and the town’s menacing doctor (Timothy Simons). In this way, the film’s themes of the oppression of women by the patriarchy’s tyranny aren’t exactly original, evoking “The Stepford Wives” and even “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

Recurring imagery includes Alice seeing flashes of black-and-white dancers in the vein of Busby Berkeley and close-up shots of blue eyeballs. Wilde uses these visuals so frequently that they end up being distracting and repetitive rather than threatening for the audience, to the point where they’re probably thinking “We get it.” A scene where the walls literally start to close in on Pugh as she’s cleaning a window has a similar effect. John Powell’s meddlesome score that practically starts off every scene also seeks to manipulate the emotions of the viewer, constantly telling them how to feel about Victory’s glamorous exterior instead of letting the film naturally guide them to those conclusions.

She’s the film’s center of gravity, taking each insane plot twist the film throws at her and grounding it in realism and emotional authenticity.

Pugh, an actress who has quickly established herself as one of the best of her generation through giving one visceral performance after another in films such as “Midsommar” and “Little Women,” is simply astonishing in a performance that goes for broke. She’s the film’s center of gravity, taking each insane plot twist it throws at her and grounding it in realism and emotional authenticity. It’s because of this that in his role, Harry Styles comes across as a deer in the headlights as he drifts through the movie’s underdeveloped plotline. This is never more true than in his character’s more emotionally raw scenes with Pugh, where Styles fails to mine the emotional depths or internal conflict of a character that already lacks personality. The other actors that round out the film’s cast, among them Olivia Wilde as Alice’s best friend Bunny and Gemma Chan as Frank’s icy wife Shelley, give performances that could merely be called effective.

The only other actor that comes close to matching her is Chris Pine, who is deliciously creepy as the cult-leader-like Frank. In a dinner scene where Alice confronts Frank about the disturbing happenings in Victory, Pugh and Pine are absolutely electric. Their characters verbally wound each other with stunning precision and mercilessness. It’s in this moment that the movie truly comes alive, crackling with intensity and tension. Ultimately, this one scene serves as a distillation of what the film could have been and should have been but unfortunately wasn’t.

The candy-colored, sun-kissed cinematography from Matthew Libatique and production design from Katie Byron is visually stunning.

It’s past this point that the film begins to falter as it fractures into a mess of dropped plot points and perplexing narrative choices, ultimately presenting a glaring disconnect between the clues that were given and the solution to its central mystery. By the end of the film, the questions of what happened to Margaret, why Alice sees a plane crash near Victory headquarters and the cause of her vivid hallucinations still haven’t been answered. The viewer doesn’t get the satisfying click in their brain that comes with realizing how all the film’s intricate details connect to its conclusion, nor do they feel emotionally fulfilled by the ending for Alice as a character.

Aside from Pugh, “Don’t Worry Darling” does have its merits. The candy-colored, sun-kissed cinematography from Matthew Libatique and production design from Katie Byron is visually stunning, all dreamy pastels and golden hues that manage to illuminate the frame even in darkness. Arianne Phillips’ gorgeous costumes also lend Victory the ’50s-era atmosphere that every other element of the film lacks. It’s unfortunate that all of this is ultimately overshadowed by the laughable twist that brings “Don’t Worry Darling” to a close.

Dominick • Dec 2, 2022 at 1:52 pm

I would say some of the pages are really interesting like overdose and theaters. I wish the World Cup was in The Shield. The newspaper could include surveys and games to ask what country will win.