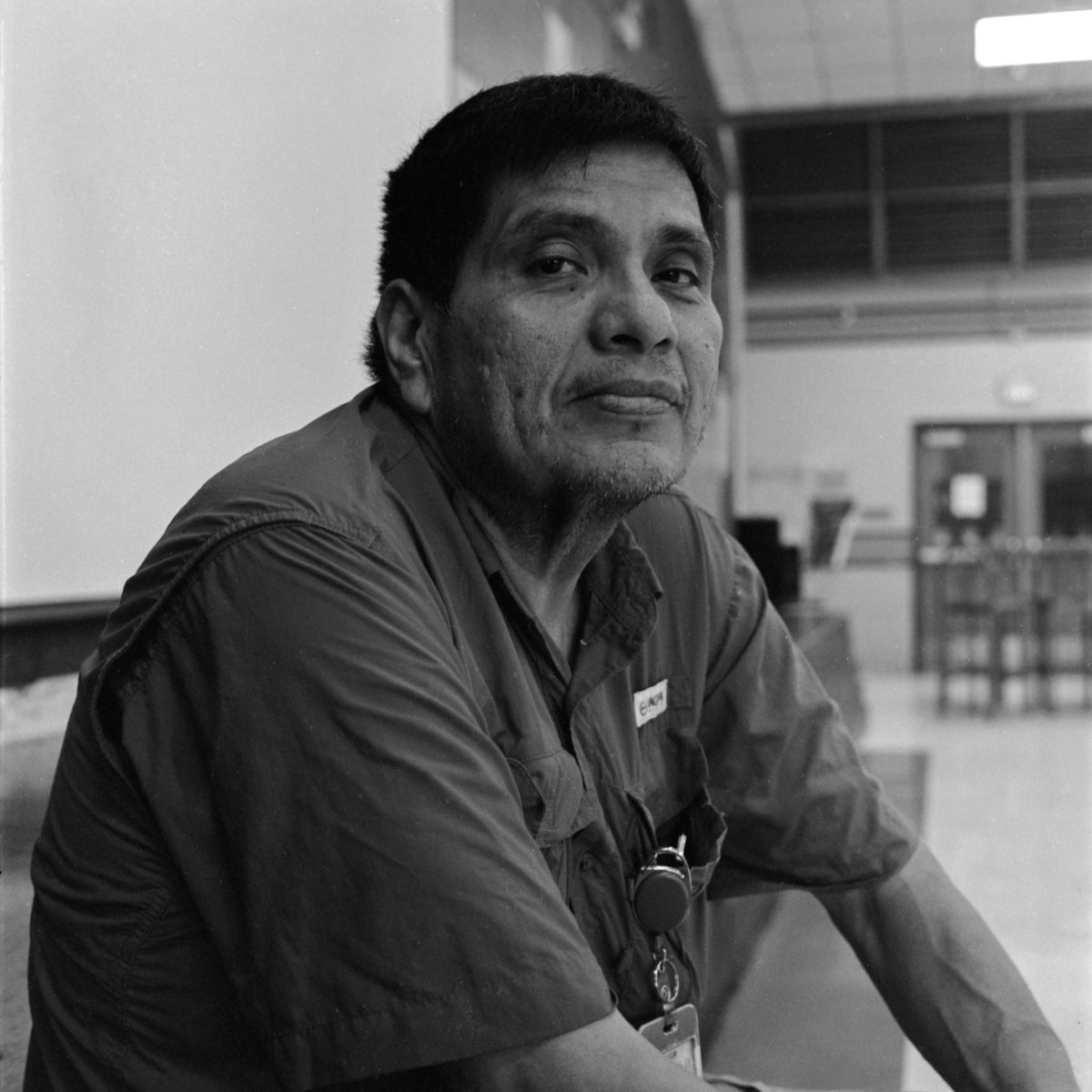

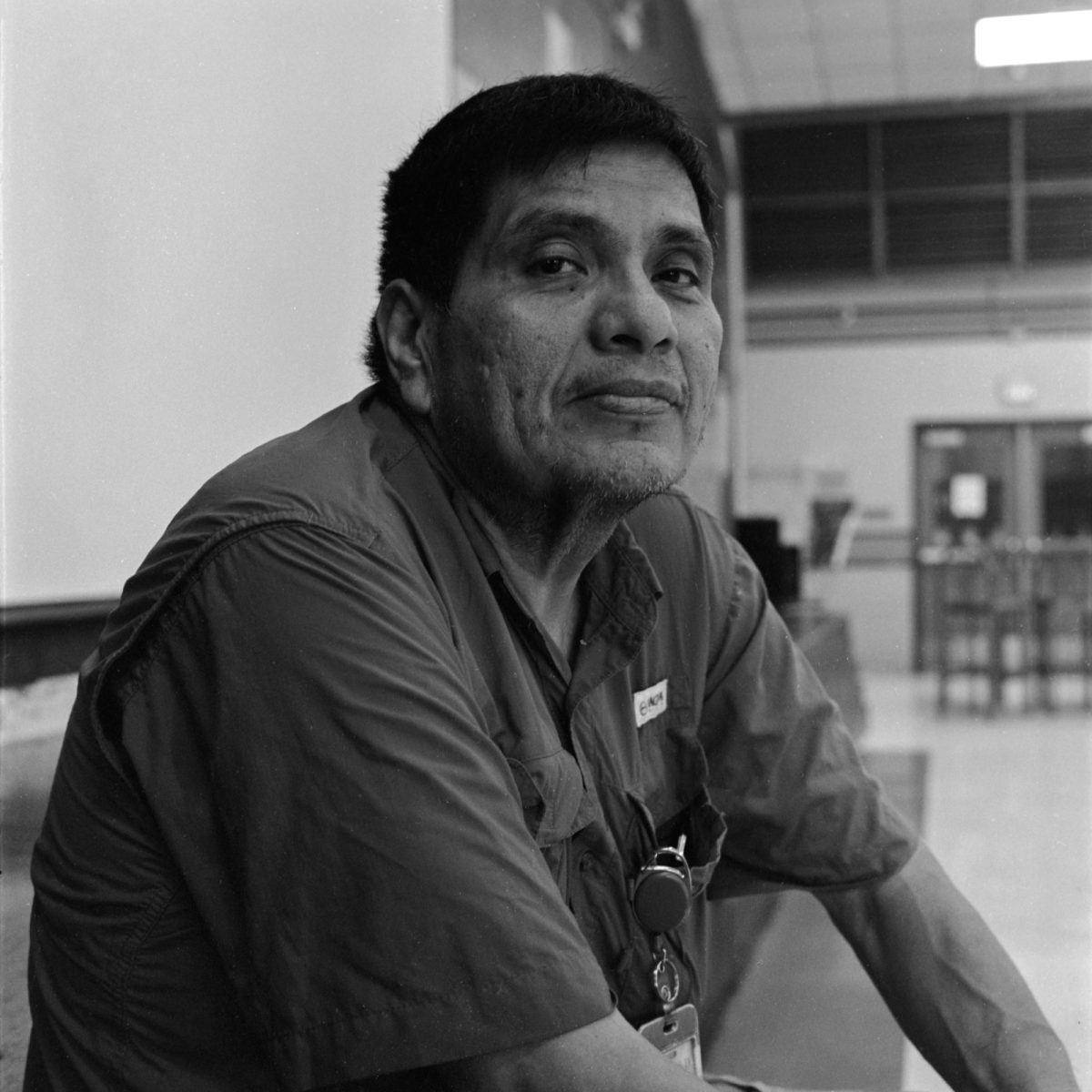

QUEENS, New York—Among the plethora of fusion restaurants and food trucks ranging from South Asian to Latin American, 25-year-old Colombian immigrant Alisson Morelis resides beneath a white pavilion on the streets of Jackson Heights cooking arepas on a portable stove top—wishing customers a good day.

“I love my arepas. I love making my arepas and the way I can sell my arepas and not just sell my arepas,” Morelis said.

Jackson Heights is the most diverse immigrant community in New York, a vibrant enclave of cultural immersion where 167 languages are spoken and 60% of its residents are immigrants. The street food vendors of this neighborhood in northern Queens emanate the quintessential diversity that is unique to this area.

As immigrants struggle to find employment in the US, many of these diverse communities turn =to the street food vending industry to earn a living by sharing traditional food from their country.

But prosperity in that industry is hard to come by in part because New York holds rigid restrictions on street vendors making it increasingly difficult for these entrepreneurial immigrant-led businesses to succeed. It has been very difficult for Morelis and others like her as many vendors face fines, red tape, and even arrests over minor violations of New York City regulations.

On May 25, Mayor Adams instituted recommendations made by the Street Vending Advisory Board in hopes of better supporting the street vending communities by reforming vendor regulations. These reforms were constructed to give vendors more government resources concerning their business and ease some restrictions. Some recommendations included forming business support for street vendors at New York City’s Department of Small Business Services, increasing access to fresh produce for New York City Housing Authority residents by bettering New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s Green Cart program, and revitalizing the Street Vendor Review Panel to be more active.

Mayor Adams announced in a May 25 press release, “Together, we can balance the needs of street vendors, brick-and-mortar businesses, and residents. These recommendations do just that by cutting red tape, creating new opportunities for street vendors to operate legally, and improving access to healthy food throughout the five boroughs.”

Despite these reforms, street food vendors’ challenges are far from over.

One main issue for vendors in New York City is the license cap which limits the number of permits that can be issued to street food vendors. The NYC Department of Consumer and Worker Protection caps the General Vendor licenses at 853 for non-veteran applicants. Limitations such as these make it difficult for vendors to simply attain a license to operate legally. If business owners don’t comply with regulations they can face heavy fines ranging from hundreds to thousands of dollars.

Morelis feels that the city’s limitations on distributions of licenses are unreasonable because the waiting list for permits is either impenetrable or it takes such a long time that people are denied legal entry into the marketplace. “We’re supposed to have a license to vendor the food but the city doesn’t have the license,” she said. “We have to wait a lot of time, years and years.”

Morelis believes that the success of these immigrant-led businesses is very hard to achieve in these conditions. She said that many vendors face major fines for minor violations from the police because of the rigid and harsh restrictions on their businesses. She worries that many vendors cannot afford to pay for these tickets, and that these regulations threaten not only the businesses themselves but the immigrant families that rely upon the income to survive.

The Street Vendor Project is a part of the Urban Justice Center, a non-profit organization that works to represent marginalized communities in New York. The project advocates for street vending rights in New York and is a prominent leader in the vendors’ movement. Their current campaigns include Lift the Caps, which pushes for the city to approve more vendor licenses and permits and The Pushcart Fund which is working to raise money for street vendors who need loans to grow and preserve their businesses.

Morelis believes her profession is vital to Jackson Heights because food vendors don’t just sell food. They represent the many cultures concentrated in the community, including her own.

“It’s been a beautiful experience because you know a lot of people in this neighborhood, there are different cultures,” she said. “I’m selling something very traditional from my country–Colombia. The way that you can know things about the other cultures–I really like it.”

Morelis feels that her and other street vendors’ roles in the community in Jackson Heights go beyond strictly what they are selling. Despite the stress and challenges of this business, Morelis persists because she believes that working on the street is about community connection, extending support and sharing culture.

“In this country, people are too alone,” she said. “A lot of people don’t have another person to talk to about things so I’m here to talk to people and say have a good day and have empathy for people. I love that.”

Collier wrote this article originally as a participant in a School of the New York Times summer course entitled, “The Foreign Correspondent: Global Reporting.”