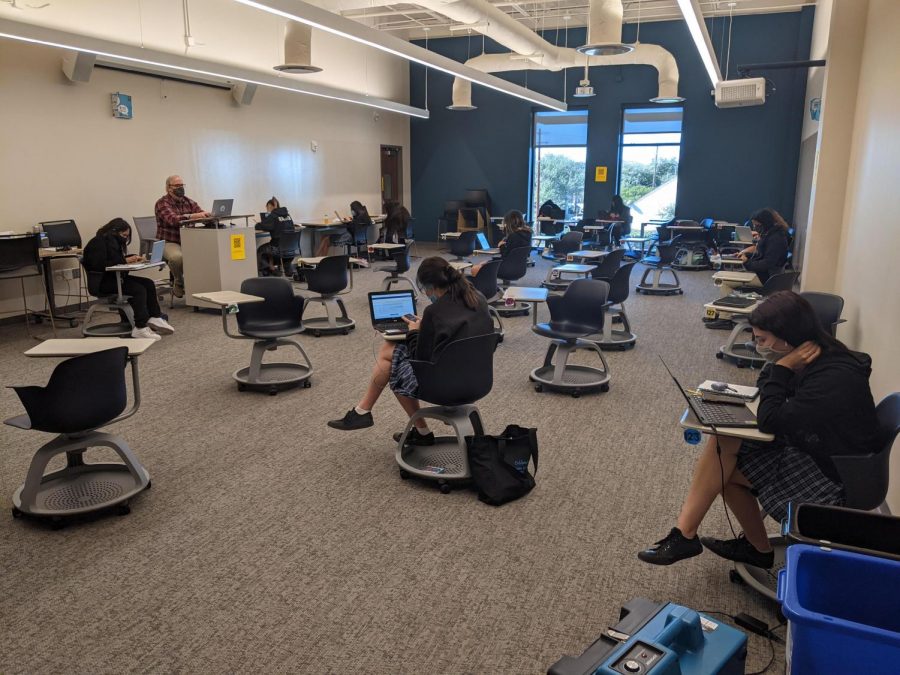

A new program is changing the way schools ensure the safety of students and teachers on campus. The program, a partnership between the teachers union Education Austin and AISD, was created with the intention of giving teachers and students control over health provisions and accommodations on campus, rather than leaving those decisions to district officials alone. The program started at the beginning of the spring semester at five schools in AISD: Bowie High, Ann Richards School for Young Women Leaders, Burnet Middle, Padron Elementary and Cunningham Elementary. The program has potential to expand to other schools in the future.

Education Austin has been working since last summer to have this program implemented in order to allow more flexibility on campuses regarding staffing and the way classes are taught. At Ann Richards, implementation of the program means a reduction in the number of teachers on campus at a time, empty classrooms while teachers are conducting Zoom classes and extended accommodations for teachers whose accommodations from last semester were denied this semester. Ann Richards math teacher Albert Marino was part of the planning committee to set this into motion.

“When it became official that we are one of the schools that is going to be a part of the pilot program, our principal, Kristina Waugh, asked for volunteers to be part of this committee that would come up with our rotations plan or whatever plan we came up with,” Marino said. “We had a few ideas kicking around, and what we ended up deciding was that, if we were in Stage 5, then one member from each department would be on campus only.”

Marino explained that there is also a plan in place to allow for teachers to be in a classroom by themselves while conducting Zoom classes.

“What would happen is all the students would go into what we call forums, which is basically a very large space, and on their conference period, each person from each department would monitor those students,” Marino said, “And during their regular classes they would be in their classroom by themselves doing all the remote teaching.”

Marino explained the reason for this new teaching plan and the difference between the class structure this semester and last semester.

“Right before the break … students would come in and go to their classes like regular, and all the teachers were expected to be on campus,” Marino said. “What the issue was, was that—Ann Richards is 6-12—well, most of the students that were coming in were younger, so the high school teachers would teach to a class of one or two people, which seemed ridiculous, and it seemed unsafe, because it’s not that person-to-person interaction isn’t great, but it’s not necessary for one student.”

Marino emphasized the importance of collectivization for teachers to have their voices heard by the schools for whom they work.

“I think a lot of teachers and a lot of workers in general, in Texas and in the South, don’t understand how powerful collective voice can be,” Marino said. “So I think this whole experience has really empowered teachers to speak out and to understand that they’re not putting their jobs at risk: they’re actually reminding administration that they don’t do the teaching, they don’t run the schools.”

At Bowie High School, the pilot program has allowed for teachers to extend their accommodations that were initially denied by the district, and for students to be in classrooms with subject-area teachers rather than in holding areas, among other things.

Bowie High School English teacher Bree Rolfe explained the process that took place on campus to allow some teachers to stay home with additional accommodations.

“What we did is we handled it within departments, and we had teachers volunteer to host additional students—with social distancing, like they put the number that they were comfortable with, and we’re not going to max out that number—and then we sort of moved students into host teacher classrooms,” Rolfe said. “And that allowed the people who were out in the fall to remain out. We also were able to extend accommodations for certain teachers who were denied.”

Rolfe said that teachers working together to create change is an effective way to improve the situation at school during a pandemic.

“I think that decisions are made at a top level, and then oftentimes, we don’t know how they will affect teachers,” Rolfe said. “I think that it’s really important, especially now, that we kind of band together to show that, ‘Hey, this is a widespread issue,’ and it’s going to affect education in a way that’s bigger than maybe people thought of initially.’ … Systemic change doesn’t happen without grassroots collective action and teachers organizing to solve problems.”

Bowie English teacher Jake Morgan agrees that the voices of the teachers are important in this process.

“I think the spirit of the plan was just like, ‘Let’s allow the people on the ground to make decisions that we think are best,’” Morgan said. “It’s kind of allowing the people who are sort of in the middle of everything, who can see and observe and understand everything, to make the decisions that work best for them. It’s less authoritarian and more democratic.”

Morgan explained that teachers are the people in education who have the closest eye on the classroom situation, and that their perspective will reveal the shortcomings of a pandemic learning environment and what solutions work best.

“I think we try to pretend that the conditions for learning are the same as they always have been, and really, that’s not the case,” Morgan said. “And I think that we all have our different risk factors and our different comfort levels, and as a parent, I wouldn’t want my child in a room with a teacher who was at that level of fear and worry. It’s better to … listen to teachers, listen to the people who are in the classroom with your student every day.”

Rolfe said that the implementation of the pilot program at Bowie is doing more than just benefiting teachers; it is benefiting students as well.

“Sometimes, in these programs, when we talk about teachers being able to work remotely, or have flexibility in working during the pandemic, what people miss is that the students will ultimately be impacted by losing their teachers, the ones that have to go on leave,” Rolfe said. “Also, our pilot program moved kids out of, like, kind of mass holding areas for remote teachers, and back into classrooms with content area teachers. So, not only were we able to solve the problem of teachers being denied medical accommodations and save their jobs, but also we found a plan that was better for students, by all working together.”

Moving students out of these “mass holding” areas and into appropriate classrooms has had a positive impact on Rolfe’s students.

“I will say that I just had class in my second period,” he said, “and one of my students who was in the library and didn’t talk because she was in the library, spoke and shared in class today because I think it’s a little less intimidating—like it’s super intimidating if you’re the only kid in the library, on Zoom to talk to me, it’s embarrassing. I have a kid in creative writing that goes, and he is real talkative, really engaged in class always, and then on the days when he was at school, because he’s hybrid, he was dead silent, and had to type into the chat. So I think the kids that I have, who were in the library who are now in a classroom, are speaking.”