The story of a scout

In working to complete her Eagle project, senior Beatrix Jackman is going where almost no woman has gone before

ONE OF A KIND: Senior Beatrix Jackman will be one of the first girls to attempt, and soon, complete an Eagle project under Scouts BSA. Photo by Bella Russo.

“On my honor I will do my best

To do my duty to God and my country

and to obey the Scout Law;

To help other people at all times;

To keep myself physically strong,

mentally awake, and morally straight.”

If the Scout Oath expresses the guidelines for being an ideal Scout, it also seems a good place to start to describe the character of one Scout: senior Beatrix Jackman. She’s strong, both physically and emotionally; resilient and committed to paving the way for those who might come after her. Despite her interest and commitment to scouting, until recently, she was forbidden from earning the highest rank in the scouting program, the Eagle Scout rank, due to her gender identity as a transgender woman.

As a woman, Jackman was not eligible to continue as a Boy scout until Feb. 1 of this year when the organization formerly known at Boys Scouts of America changed its name and allowed girls to join the Boy Scouts. Allowing girls ages 11 to 17 to join BSA completed a transition for the organization that was first announced in 2017. Girl members have been able to join Cub Scouts since 2018. According to an Feb. 1 article published in The Hill, more than 77,000 girls have joined the Cub Scouts since girls were eligible to join.

For Jackman, the new gender admissions policy solved what had been, to that point, an unsolvable dilemma: to be true to herself and remain a Scout, she could either hide her gender identity or practice lone scouting. Neither solution was acceptable to her.

“I stopped for a while,” Jackman said. “I wasn’t going to hide who I was anymore, and [doing it alone] isn’t what [scouting] is about.”

Jackman became involved with the Boy Scout program in elementary school, joining the troop stationed at her school, Highland Park Elementary. She joined because she wanted to make a difference in her community and heard that Boy Scouts was the best place to do so. As she got older, and began to realize who she was, Jackman’s participation in Boy Scouts was compromised. She left the organization for many years, only becoming affiliated this year after the change to Scouts BSA.

“[I came back] to partially lead the way for other girls like me, but also because I was almost done, and I want this closure,” she said.

The new inclusive policy of the Boy Scouts of America, now Scouts BSA, came as a surprise to the public. The Boy Scouts have been iconic in American culture for more than 108 years. Boys ages 11 to 17 join in order to learn lifelong skills of leadership, wilderness survival and adaptability. The highest achievement for the committed scout is becoming an Eagle Scout. To earn Eagle status, the scout must earn 21 badges and complete a unique, personalized Eagle Project that positively affects a community and involves at least two scout-chosen and scout-led volunteers.

Though the Boys Scouts of America has been recognized for the skills learned by its participants and the lifelong friendships that are made between scouts, the organization, like most its age, has faced controversy in the past for restricting its membership. The organization allowed troops to be segregated until 1974, despite public school segregation being declared unconstitutional in 1954.

Until 2014, the organization banned all atheists and those not willing to subscribe to their Declaration of Religious Principles. In 2012, the Boy Scouts of America were under fire for upholding a 1980 policy that echoed the military’s “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, excluding openly gay scouts but allowing those who were closeted about their sexuality. At the time, the organization claimed that homosexuality went against it code of conduct. On May 23, 2013, the organization’s national governing body voted to allow boy members regardless of their sexual orientation.

While change is always difficult, the change to admit girls into the Boy Scouts has been particularly contested both inside and outside the organization. The Girl Scouts of America has criticized the move, extolling the merits of single-gender environments for girls. The Girls Scouts even sued the Boys Scouts when the organization changed its name.

The external debate was mirrored by an internal one within the organization. A former Eagle Scout, who wishes to remain anonymous to preserve current relationships, described his initial opposition to allowing girls into the organization: “When I first heard the name change, it was in the news. My mom and I were really against it. We aren’t really happy because I had worked through this and earned my Eagle Scout under the name Boy Scouts of America. I really wanted to represent that.”

Another former Eagle Scout, who also asked to remain anonymous, echoed these concerns. “I was a little skeptical at first because it’s called Boy Scouts. And there’s also The Girl Scouts. I agree that there are flaws, and I think it should teach the same things as the Boy Scouts teach, but the whole point of Boy Scouts was centered around being led by boys.”

Both Eagle Scouts specifically mentioned the Girls Scouts as an already existing alternative scouting option for girls and said that their objection was held by many Boy Scouts. Despite these objections, however, the national leadership of Scouts BSA pressed ahead with the policy change.

“I could not be more excited for what this means for the next generation of leaders in our nation,” said Michael B. Surbaugh, the chief scout executive of Scouts BSA said in a Feb. 1 press release. “Through Scouts BSA, more young people than ever before—young women and men—will get to experience the benefits of camaraderie, confidence, resilience, trustworthiness, courage and kindness through a time-tested program that has been proven to build character and leadership.”

In 2018, the newly named Scouts BSA agreed to let all genders in their organization starting in February. On Jan. 31, an 18-year-old Jackman received an extension to complete her Eagle Project. Scouts age out of the organization when they turn 18, but an extension allows the scout six extra months in the program.

“It let me work on my stuff for six more months,” she said. “It started in February, and it is officially April. The clock is ticking.”

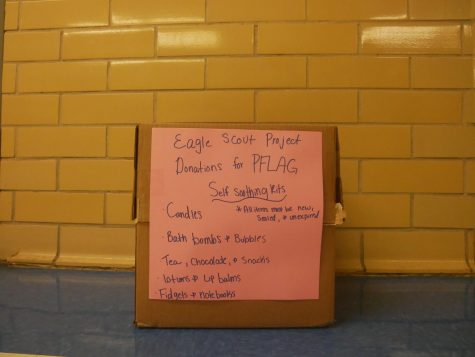

Since Eagle Projects require so much time, coordination and effort, many scouts choose a cause that impacts them personally. For her project, Jackman is doing the same, making what she calls “self soothing kits” for struggling LGBTQ youth. She is choosing to work with an organization called PFLAG or Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, an organization with more than 400 chapters that supports families and friends of the LGBTQ community through counseling, education and policy change.

She chose to work with them because of their large reach and resulting impact. Jackman’s inspiration for her self-soothing kits comes from personal experience. “I have depression,” she said candidly. “I went to DBT (dialectical behavior therapy), where self soothing kits were taught.”

Knowing firsthand the struggles of a transgender kid, Jackman aims to use her project to give struggling people, who were in a place where she’d previously been, the support she found helpful.

Jackman’s biggest obstacle currently is a lack of donations, which she relies on to create the kits. She asks that students bring donations to help her complete her project and benefit a marginalized population in Austin at the same time. Jackman would like items for self-soothing kits to put in a donation box located in front of the main office. Jackman suggests, “bath bombs. Soothing stuff. Self-soothing not necessarily self care. Self-soothing is like chocolate.”

Jackman is thankful for the Scouts BSA name and policy change, as it gave her a chance to get the closure she needs.

She supports the inclusive stance of the new Scouts, saying that being a part of a close-knit troop is the most important benefit of scouting. For Jackman, the strong group connection comes with good and bad.

“I think that the group mentality is important, but it also causes change to be slower because the people in charge don’t see what’s happening unless someone says something,” she said. “There’s a pressure, I feel, in large groups to not say that something’s bothering you because of social pressures.”

She added that there are smaller indicators that the group’s change is still a work in progress. “They haven’t updated everything,” Jackman said. “Their calls systems and a lot of stuff still say the Boy Scouts of America.”

Jackman remains hopeful that Scouts BSA keep moving toward full integration for all troops under the Scouts BSA umbrella. While she’s optimistic for the group’s long-term future, she also acknowledged “it’s a process.”