سلام, Welcome, ښه راغلاست

With the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, Austin ISD has welcomed about 400 refugees across district campuses including Mac

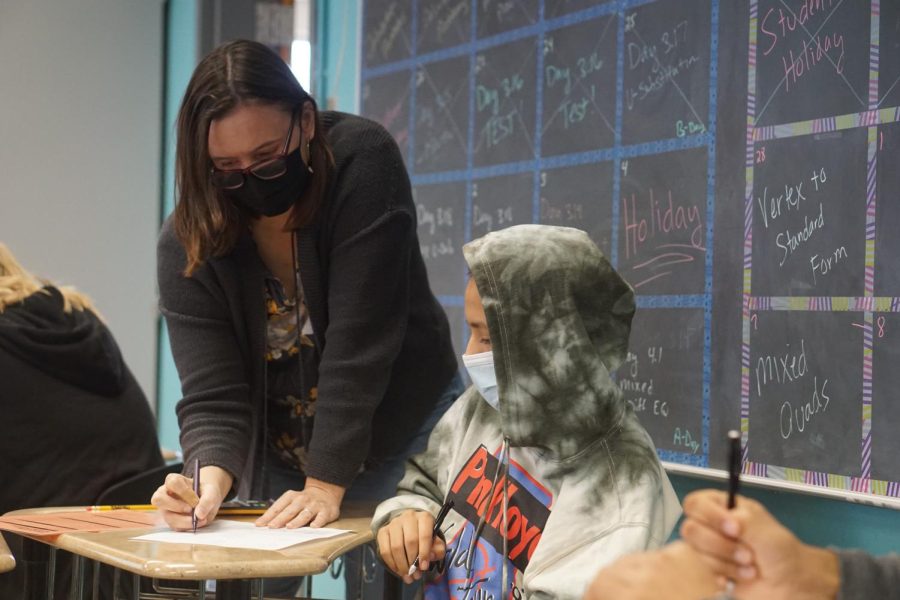

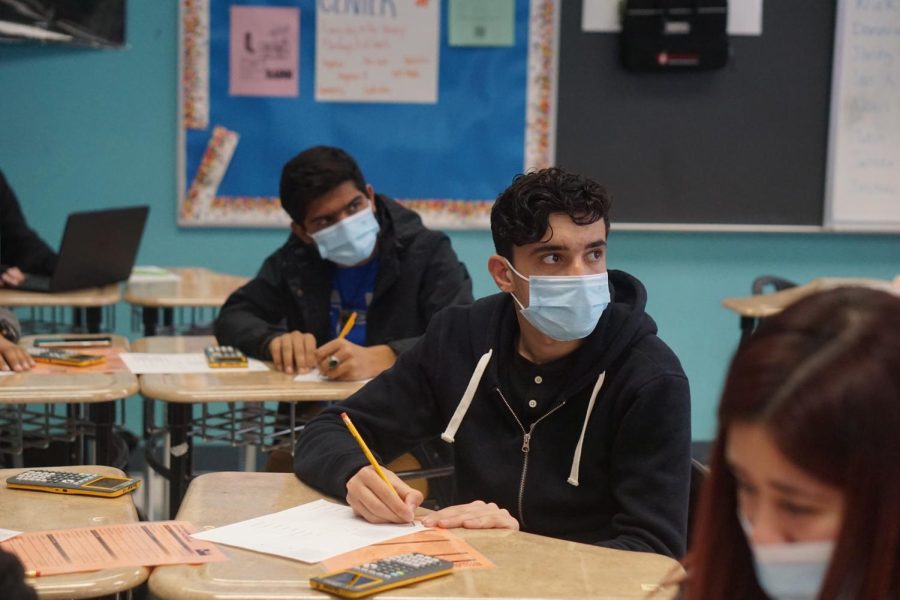

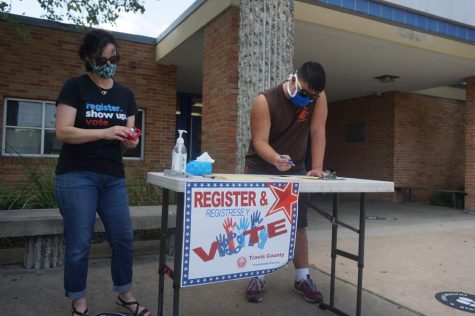

Afghan students Uzma and Deba work on notes in math. Their class has a total of 6 afghan students.

It’s 2014 and the Austin Airport is busy. It’s nothing like the movies that Elyas Akbari has seen. He hasn’t been to his country, Afghanistan, in five years. He arrives at the place he’s supposed to call home. It’s an apartment with a single couch, a dining room table, and two beds. He lives there with his wife and daughter. They wake up to sirens at least once a week. They don’t feel safe.

“When refugees first come here they need a home,” Akbari said, “They need furniture. Second, they need a car, so they can go shopping, and third, they need friends, so they can have connections. When you come here and everyone’s speaking a different language it’s crazy. They need someone to help them.”

Akbari has been living in the United States since 2014. His daughter is in school in Austin ISD, and since coming to Austin he’s become adjusted to his surroundings with the help of the Afghan community and volunteers.

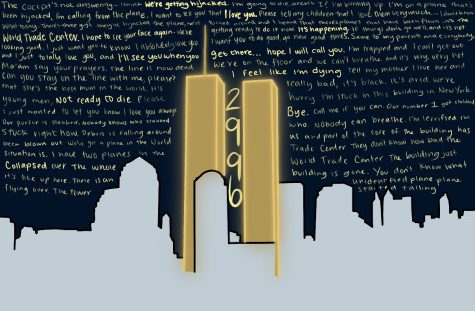

In August, after a 20-year occupation, the United States withdrew troops from Afghanistan. The Taliban took over the country. On Sept. 16, 2021, Texas prepared to receive about 4,000 Afghans, according to CBS News, but according to Refugee Services of Texas, 9,762 refugees have come to Austin from Afghanistan in the last six months.

When refugees first come here they need a home; they need furniture; they need a car; they need friends. — Elyas Akbari

“When a population gets displaced from a country, they end up typically in a refugee camp in a neighboring country,” Refugee Services of Texas CEO Russell Smith explained. “They can be there for many years. The vast majority either stay in the country they end up in or move back home if it is safe. A small percentage get resettled to a third country, and the U.S. normally takes the majority of those.”

Many of these refugees are children and teens who need an education.

“We have welcomed a lot of Afghan students in the last 6-7 months,” said Dr. Cody Fernández, AISD Director of Secondary Multilingual Education. “AISD has over 900 refugee students across the district, and approximately 400 of those students are from Afghanistan. Collectively, AISD staff are working hard in allocating resources that meet the needs of our Afghan students districtwide.”

McCallum has welcomed many Afghan students into their classes. Some teachers have up to 10 students in one class.

“Part of the resettlement process, when you come into the U.S. from a situation like that, is that you have to spend some time at the U.S. military base, or one of their facilities being checked and rechecked,” science teacher Sarah Noack said. “They’re just now coming into school from that process and being put into society. So my classroom just started having more and more Afghan students.”

English teacher James Hutcheson has several Afghan students in his class. He also helped set up WiFi and organized places to pray for many of his students, as well as welcoming students into his classroom during lunch to hang out.

“The language barrier is a challenge,” Hutcheson said. “It is incredibly challenging to help someone develop linguistically when your lexical sets and syntax differ so much. The other challenge is that I’m essentially teaching two classes simultaneously. I try to think like I’m teaching a Spanish 1 class. It can be a lot to juggle, but I’m having a lot of fun doing it.”

According to Fernández, making these new students comfortable in their new environment is the best thing that teachers can do.

“It is a lot of change for a student to move to a new country and be immersed in a completely different language and culture,” Fernández said. “One great way to do this is by learning as much as they can about the students and their culture. A little research can go a long way. Our Multilingual Education Team has been providing learning sessions for staff to have some cultural and linguistic backgrounds of their Afghan students.”

Noack has also welcomed many new students to their class. The language barrier and the feeling of having to teach two classes simultaneously presents a great challenge for them, too.

“Afghanistan has lots of different languages,” Noack said. “Each student that comes in might speak something different. Some of them have never been to school before, like at all, so helping them is sometimes a challenge because they may not read their own language. You can’t use Google Translate, because they can’t read what you’re saying on their end. I don’t know what to do with these students in my classroom because I’ve got multiple languages, maybe in one class period without a supporting student who also speaks English. Or I have a situation where I have a student that can’t read in their native language. I need help.”

I’m essentially teaching two classes simultaneously. I try to think like I’m teaching a Spanish 1 class. It can be a lot to juggle, but I’m having a lot of fun doing it. — English teacher James Hutcheson

Fernandez advises teachers to use visuals like pictures to help educate their students.

“Pictures of words or content and opportunities to demonstrate what the students understand without having to say it at first can be extremely helpful,” Fernandez said. “Most of these students have witnessed the most emotionally disturbing experience. Most and foremost, teachers ease their experience by ensuring their safety, and by fostering a welcoming environment in the classroom.”

Hamedullah Zadran, a student of Noack’s, and also a student who came to the United States from Afghanistan a few years ago, originally found the language barrier a challenge.

“When I came to the U.S., it was a big problem as I didn’t speak any English,” Zadran said. “It’s not a challenge anymore. In the USA, I have a better environment and life. Knowing how the war was there did not make me want to stay there. I also like how people are very nice and helpful as a lot of people helped us and our family when we came here.”

While the new students learn English, the teachers are also learning from their students.

“I’m learning a lot about language acquisition in a practical setting,” Hutcheson said. “I’ve studied this in textbooks, but being in the situation feels much more enriching. Students and teachers need to be kind and understanding. These kids are smart, and many are as educated as our students. Most speak multiple languages. They just need to learn ours. Also, we need to be tolerant of differences in cultural values.”

As their students learn, teachers have begun to learn from their students. Noack has begun to learn some Pashto, one of the many languages taught in Afghanistan, including Pashto colors.

“I’ve learned that their backgrounds are extremely varied, and their home lives are all really different,” Noack said. “Depending on how big their family was, or where they lived in Afghanistan, their experiences were different, just like they are for us here in the U.S. But they all have some commonalities, right, like we do here. It’s been really fun talking to them about their food. They all love to talk about their food. They seem like they have a lot of pride and love for their food and their food traditions.”

McCallum parent Kathryn Rodgers volunteers to help refugees.

“It’s really fun to do tangible good,” Rodgers said. “You know, in our lives, we want to make the world a better place. Sometimes it’s just really simple. If you can drive your car over and be like, hi, I brought you a microwave. Or, you know, you needed a phone for your wife and someone in my neighborhood gave one away. Or with people who have children and I bring a box of toys.”

She speaks on how much she appreciates how welcoming the Afghan community is.

They’re very hard working. A lot of them work, you know, a full-time job and then drive for Uber, as well. And the women are amazing cooks. The meals they make are just crazy good. — McCallum parent volunteer Kathryn Rodgers

“They’re very hospitable people,” Rodgers said. “They always want you to come in and drink tea or have juice or they’ll even make you like this whole big meal that you weren’t expecting. And, you know, in America, if you say, ‘Hey, why don’t you come to dinner?’ you won’t necessarily bring a whole bunch of people with you, right? My friend and I were invited to dinner and they were like, ‘Where are your husbands?’ ‘Where are your children?’ ‘Why didn’t you bring everyone?’”

Zadran’s Afghan culture is very important to them.

“My favorite thing about Afghanistan was the culture and how we all used to hang out with our family during Ramadan and Eid fights,” Zadran said. “During Eid, we would always get money from our family members, with that money we would buy little guns that shoot out small non-hurtable bullets. We would have fights with other communities as if raiding them.”

Transitioning from one community to another is a challenge. When you have a student in your class from Afghanistan be sure to welcome them and treat them with respect.

“Texas is a welcoming state, and refugees add so much to our communities.” Smith said. “We have been overwhelmed by the support from the community. It is heartwarming to see how people want to help.”

![With the AISD rank and GPA discrepancies, some students had significant changes to their stats. College and career counselor Camille Nix worked with students to appeal their college decisions if they got rejected from schools depending on their previous stats before getting updated. Students worked with Nix to update schools on their new stats in order to fully get their appropriate decisions. “Those who already were accepted [won’t be affected], but it could factor in if a student appeals their initial decision,” Principal Andy Baxa said.](https://macshieldonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/53674616658_18d367e00f_o-600x338.jpg)

Ted • May 3, 2022 at 2:31 pm

I feel like this article could have had a bit more nuance to it. While to the premise is quite interesting, and something that every American needs to know about. How we, and the people we elect to impact the lives of many people, including the displacement and subjugation of many other people around the world. In this 20+ year war (1), the US helped displace over 515,000+ Afghans (2) because of our invasion of their country to “fight terrorism”, after we historically supported these terrorists. While indirectly, the US did support the Taliban and funded their “freedom fighting” (3). To justify this war and slaughter of civilians in the Middle East, the US government has swept this under the rug. But I digress.

The feeling I get from this article is that the original premise was to see how the displaced refugees from Afghanistan were assimilating to American culture, the people who destroyed their country in the first place. The article could have had a nuanced and groundbreaking take on it, but instead, it gave off a so-called “White saviour” feeling. Instead of expanding on how, why, and who these Afgan refugees are, the article focuses on who is helping them. How others are adjusting to having refugees around them, from the war that their country started. It feels disrespectful to the actual Afghans who are fleeing their home from a war that our country started and the intense trauma that comes with that.

The title and header of the articles are misleading in making the reader think that we would be getting a nuanced and informative article about the Afghan refugees that are in our community and getting to get their point of view on being displaced from home in a foreign country.

It is disrespectful to only include barely two actual refugees and their opinions in this article about them, but three people who are helping them. It makes the point less valid and less appealing. It makes the reader [myself] think that this is just a fluff piece about someone’s new pet project, helping Afghan refugees. I hope that in the future this nationally recognized newspaper will do better at taking important and more nuanced approaches to difficult topics like refugees and international displacement.

Works Cited

Cordesman, Anthony H. “Reshaping U.S. Aid to Afghanistan: The Challenge of Lasting Progress.” Center for Strategic and International Studies |, 23 February 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/reshaping-us-aid-afghanistan-challenge-lasting-progress. Accessed 3 May 2022.

Council on Foreign Relations. “The US War in Afghanistan.” Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/timeline/us-war-afghanistan. Accessed 3 May 2022.

Loft, Philip. “Afghanistan: Refugees and displaced people in 2021 – House of Commons Library.” Commons Library, 16 December 2021, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9296/. Accessed 3 May 2022.

online