Teens locked on screens

After spending more than a year learning online, students struggle to set technology aside in person

As the first generation to grow up with an abundance of screens and handheld devices, today’s teenagers have the challenge of managing dependence on screens and creating healthy screen-time boundaries.

March 10, 2022

After living with eyes glued to screens for two pandemic-ridden years, people all over the world are now more reliant on electronic devices than ever before. But with school back in person and opportunities to socialize face-to-face at last, some high schoolers are struggling to put their phones aside and step back into the world. As some become increasingly dependent on the escapism they find in technology, with serious consequences for mental health and grades, internet addiction has increasingly become a serious concern.

Even before the pandemic began, a mental health crisis was prevalent among American teens. United States Surgeon General Vivek Murthy described a 40% increase in “persistent sadness or hopelessness” for high schoolers from 2009 to 2019, with one in three students experiencing the symptom. According to Murthy, teen anxiety and depression have increased since the pandemic began and the mental health crisis has become even more critical.

“The COVID-19 pandemic further altered their experiences at home, school and in the community, and the effect on their mental health has been devastating,” Murthy said in an advisory on the teen mental health crisis. “The future well-being of our country depends on how we support and invest in the next generation.”

Through the uncertainty of the pandemic, phones and electronics were a lifeline for teens: the devices that connected them to the world and their friends, and the devices that served as schools, gyms, coffee shops and everything in between. According to a study by JAMA Pediatrics, recreational screen time doubled among teens during the pandemic from estimates of 3.8 hours every day to 7.7, in addition to the five to seven hours many spent online for virtual school. Although there are positives to increased screen time, such as greater connectivity, researchers have found that high amounts of screen time often correlates with poor mental health and coping strategies.

According to the website for Zilker Center, an Austin institution that offers treatment programs for the issue, technology addiction blends expectation and reward with the release of dopamine and other chemicals to create a “high.”

“The reward in question might be winning a challenging video game, or getting a high number of likes or views on an Instagram post or TikTok,” the Zilker Center website says. “Over time, your teen could begin to crave the dopamine release they receive from technology—resulting in their needing even more stimulation to achieve the same feel-good effect.”

After COVID hit, teachers and students alike had to adapt to a fully online learning model. Once this school year began, many teachers made the decision to keep their lessons somewhat digital-based, with students completing work online in order to decrease paper usage and keep all resources in one place. This increases the overall time students spend on screens.

Counselor Lauren Croom views technology in the classroom as a “delicate balance,” as it can distract students from lessons if they are not disciplined enough. Additionally, Croom has noticed that increased cell phone usage can disrupt students’ sleep schedules, which has a negative effect on their academic performance.

“I think that while it’s necessary to have Chromebooks and technology, at some point, I think it is really important for us to also just have human interaction and be able to talk and communicate and collaborate,” Croom said. “I feel like we’ve lost a lot of those skills through constant staring at screens.”

If world history teacher Kristen Wachsmann could make the rules, all teachers at McCallum would have a designated place for student phones in their classrooms to eliminate distractions. [Editor’s note: since granting The Shield this interview, Wachsmann has left her teaching position at McCallum to take a job in sales at a tech company.]

“There’s this tendency to think that introducing technology, whatever it may be, is somehow going to cure the problems that we face in public education,” Wachsmann said. “I don’t agree with that analysis. I don’t like using Chromebooks all the time, because research shows that people engage better and learn better when they can read from a hard copy, especially when you have a developing brain. I think this tendency to go all in and have 100% of things be online or digital is the pendulum swinging too far.”

Wachsmann hopes to use her classroom as a space for students to sharpen the social skills they may have lost when school went entirely virtual and implement a blended online and on-paper teaching strategy to allow all types of students to thrive.

“When we’re in the classroom, the most valuable resource we have is each other,” Wachsmann said. “I want to make sure we’re using that. I think tech can be incredibly useful at home as you’re learning or when you’re applying your knowledge. But in the classroom, I really want to maximize people’s interaction with each other.”

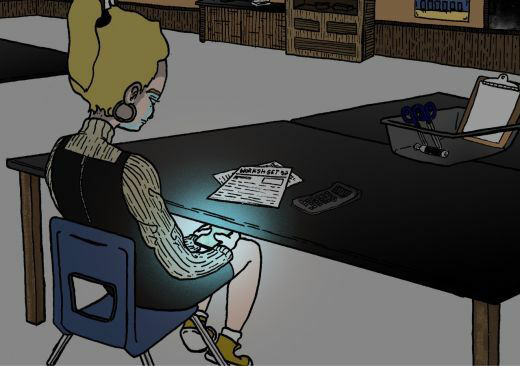

Counselor Cristela Garcia said multiple parents have contacted her due to their students’ inability to learn with electronic devices around. According to Garcia, these complaints have nothing to do with digital-based learning but with students’ lack of discipline.

“They’re complaining that their child cannot learn because they are so fixated on going onto other sites,” Garcia said. “We’re not going to win against Snapchat, Instagram, games. We’re not going to, that’s more interesting. They’re mad at those things that are distracting students from what they’re supposed to be doing.”

It is clear from the initiatives listed on Austin ISD’s “Everyone: 1” Chromebook program that the district plans to continue using computers in school to support students’ learning.

“Technology helps students take more control over their own learning,” the Austin ISD website says. “They will become better at learning how to make their own decisions and become better thinkers, ultimately resulting in stronger achievement.”

As the first generation to grow up with an abundance of screens and handheld devices, today’s teenagers have the challenge of managing dependence on screens and creating healthy screen-time boundaries. While the pandemic increased reliance on technology, the screens are here to stay, both those in pockets and those in classrooms. For those who struggle, there are resources available, including speaking to a school counselor or a therapist, and in severe cases, attending an internet addiction treatment facility like the Zilker Center.