Covered from head to toe in a pale blue gown, gloves, face shield and an N95 mask, Lindsey Wagner is only inches away from a coronavirus patient. The air is still. Uncertainty fills each corner. The soft, muffled chatter of the television across the room catches her attention. She turns. A news anchor, a violently red headline about this many new deaths, that many new risks, the statistics flooding the screen. This is real, she thinks to herself. This is really happening.

Nursing 101

Lindsey Wagner, 27, is an Intensive Care Unit nurse located in Denver. Each morning, she carefully slips on a mask and takes a deep breath, battling the all-so-familiar coronavirus on the frontlines. She knows the risks but also the profound payoff of being an ICU nurse right now. But long before she had heard of the coronavirus or COVID-19 — even before the idea of applying to nursing school even danced across her mind — Wagner spent her time not in training classes or at the hospital, but in the McCallum band hall.

Lindsey Wagner was a self-proclaimed “band kid” in high school.

“McCallum was definitely the right vibe for me,” she said. “The creativity, the music, the people, and just the smaller environment. I wouldn’t have changed it.”

Mac band director Carol Nelson, a musical mentor then and now, also expressed gratitude reflecting upon Wagner’s time in the program.

“She was very responsive and very dependable,” Nelson said. “A hard worker, and a really good euphonium player.”

Nelson also reminisced upon the ways in which Wagner would push above and beyond, both inside the band hall and out, recalling her challenging UIL solos and consistent work ethic.

“Basically a quality person in all regards,” Nelson expressed. “I bet she is a great nurse!”

After graduating in the spring of 2011 and with fond memories of Mac still close to her heart, Wagner packed up her bags and made the four-hour, two-minute drive up to Nacogdoches to attend Stephen F. Austin University. When she first started planning her postsecondary future, Wagner knew that she wanted to be a nurse.

“When I applied for college, I had already known that I wanted to at least try being a nursing major,” she said. “I don’t have any nurses in my family. I think the idea of becoming a nurse just occurred to me one day and I was like, ‘that sounds cool.’”

On top of being cool, it was also a test of her will and her character. Wagner shared that her years at nursing school were some of the most formative for her growth not only as a nurse, but also as a human-being.

“Nursing school is really hard,” she said.”I think that’s going to be generalized to wherever you go to study nursing. It’s very science-heavy, but there’s also critical thinking. Then there’s the clinical aspect of it. You’re shaking in your boots the first time you’re taking care of an actual patient. … But everybody works together and helps each other. You can’t be competitive in nursing school. It’s good to have everybody else on your team, striving for the same goal. Work ethic is what I got out of nursing school.”

With a diploma in one hand and the grit and determination to put it to use in the other, Wagner set forth on her nursing career. Moving out to Denver just last August, Wagner is fairly new to the Mile High City.

But just as Wagner’s long-awaited summer was finally approaching, the hiking expeditions and city explorations she was looking forward to were pushed to the backburner. In their place stood a virus: the coronavirus, COVID-19, which has consumed the minds of the global public, devoured the days and nights of thousands of U.S. workers, and taken the lives of more than 300,000 humans globally.

Each morning, Wagner’s 12-hour, 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. shift begins right at the hospital entrance, waiting in line to get her temperature checked so she can be cleared to work for the day.

“If your temperature is within the healthy range, the hospital staff checking temperatures hand you your mask for the day,” Wagner said. “I can’t even go to work without being checked off, confirming I can be here and safely practice.”

Immediately after, Wagner changes into a new set of scrubs in the hospital changing rooms, part of a protective personal equipment, or PPE, effort to prevent the spread of coronavirus from the outside world into the hospital. On a typical day before the coronavirus pandemic, Wagner would arrive at the hospital already dressed in her scrubs.

“[The new changing system] seems like a small thing, but even that’s a change from my normal,” she said.

Next comes the bedside report, a three-way exchange between Wagner, the night-shift nurses and the patient that occur between every shift. But the words “bedside report” don’t exactly hold true in a COVID-plagued ICU unit.

“Normally, bedside reports are a practice all hospitals try to do where two nurses from each shift go to the patient’s room together to get the patient involved in the changing of shifts,” Wagner said. “But now, we’re trying to limit how many times we are in the room.”

Bedside reports aren’t the only hospital policy that’s changed due to COVID-19.

“Day to day, it’s a very different flow because I’m used to practicing hourly rounding, going in every patient’s room every hour, but now we only go when absolutely necessary,” Wagner said. “We’re really trying to cluster care, to do everything at once and be in the patient’s room as little as possible. It’s a little bit hard for nurses because it feels almost like a control thing, not being in the room as often, but it’s for everybody’s safety.”

In lieu of the face-to-face interactions to which Wagner is accustomed, nurse-to-patient communications have become digitized.

“The nurses call into the patient’s rooms through their room phones,” Wagner described. “We also have monitors that show the patient’s oxygen levels at the nurses station.”

This routine wasn’t automatic when the coronavirus outbreak began. It developed over time. The first transition occurred when the orthopedic and spine unit, Wagner’s former home at the hospital, transformed into the hospital’s COVID-19 unit.

“Nobody knows what a COVID unit is supposed to look like or how it operates, so there was a lot of stress in the beginning since things just change every day,” Wagner said. “At first it felt very makeshift and nobody knew the exact right things that we were supposed to be doing, which was stressful.”

As the new hospital procedures became routine for Wagner, so too did the risks that came with them.

“At first, we were seeing a lot of younger patients,” she recalled. “It wasn’t just the 65-plus, like the news was saying. I was seeing healthy people in their 30s who were going to be hospitalized for COVID. I thought to myself, ‘Yes, I’m young and healthy, but I’m seeing young, healthy people also be taken down by it.’”

And so, for Wagner, work and risk began to come hand-in-hand.

“I would say we have adequate PPE, but I’d feel more comfortable with more N95 masks,” she said on April 23. “We get one surgical mask and a face shield, which has shown to be appropriate for protection, but I do know nurses that have [the virus]. I try to think, it doesn’t necessarily mean they got it at work. We’re pretty vigilant. But we do get a daily COVID update, and as of the last one, there were 21 colleagues that were positive. So there is a risk.”

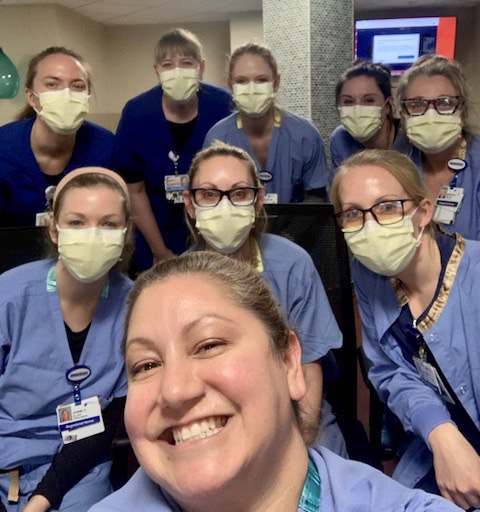

For Wagner, however, the strength and community of her fellow nurses aid the process of remaining calm under this pressure. “I always knew nurses were badass,” she said with a laugh. “But now it’s been like… everybody has something to contribute. And when they do, I think the world of them.”

The eye of the storm

In the midst of the COVID chaos, Wagner continues to push through, fueled by her patients and their families.

“When patients get better, it feels that us nurses are making a difference,” she said. “When family members are calling up and are just so appreciative of us being there and doing what we’re doing, then it feels like it’s worth it. I would want this kind of treatment for my family and for myself. And that’s just nursing in general, so it doesn’t feel like a huge stretch we should do this.”

But Wagner’s days don’t pass without their challenges.

“I have a few closer co-workers, but I haven’t worked there that long. I’m kind of a reserved and quiet person. That was one thing I brought up with my therapist. I am having such a reaction to this and am struggling at home. And it seems like I don’t know what other people are going through because at work, you show up and you’re there to work,” Wagner said. “At first, I was like ‘Is it just me that’s having such a hard time?’ But it comes out in spurts, how the other nurses are doing. So I know we’re all kind of on the same page.”

And for Wagner, taking time for herself can be one of the hardest challenges of them all.

“One Sunday, after a very hard Saturday shift, I was feeling the burnout, and I just didn’t feel like it would be the best for me or my patients to go into work. I just needed to fill my cup before I could help others,” Wagner confessed. “But I had such guilt even for doing that. It’s nice that nurses are getting recognition, but there’s pressure, too.”

A message to remember

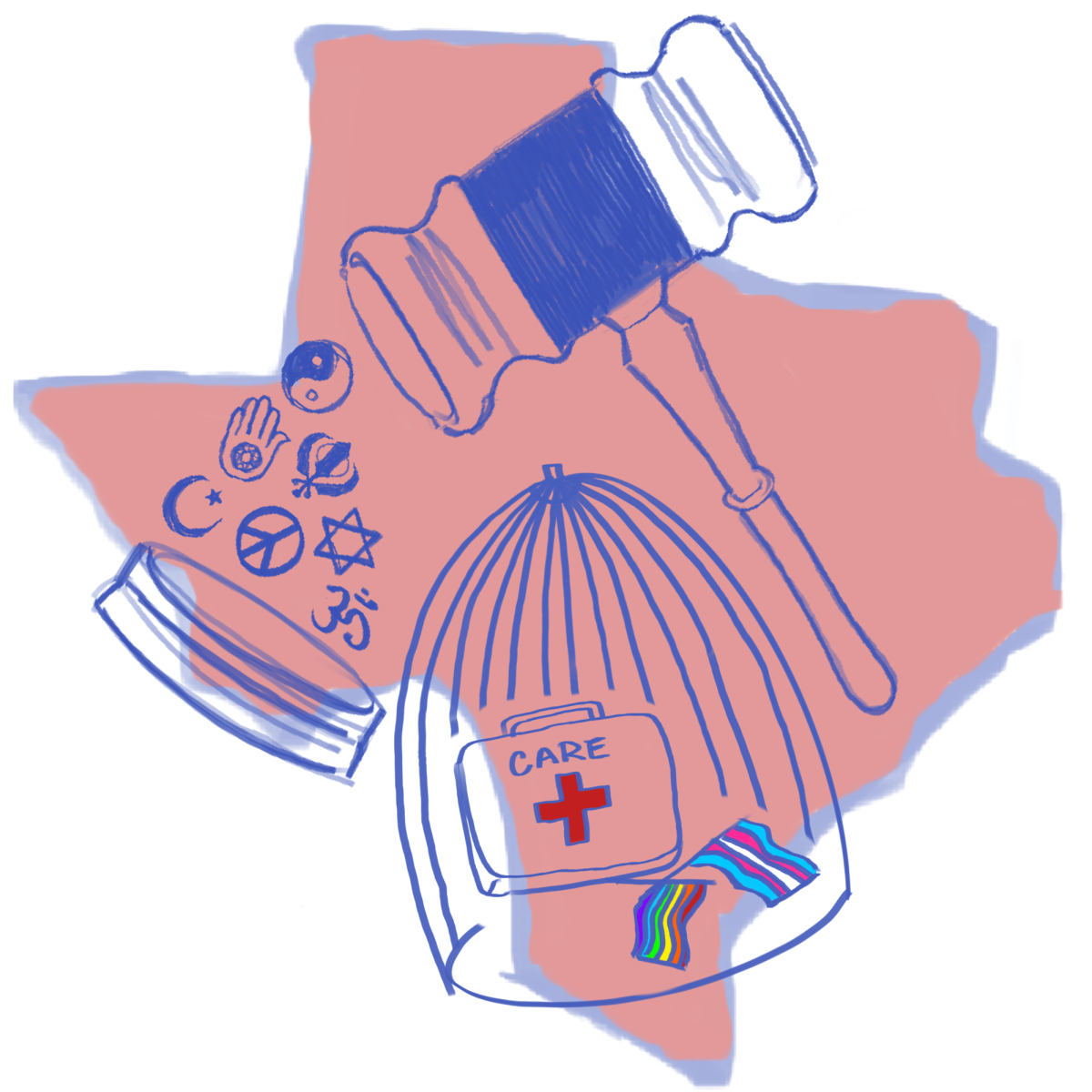

On the weekend of April 19, downtown Denver was a wash of red, white and blue, flooded with handheld American flags and cardboard signs. “Give me liberty or give me COVID,” read the messages sprawled messily among the signs. “Give me a haircut,” read one. “Land of the free” and “Make America Free Again” read two others. Shouts rippling through the air and the decisive honking of horns echoed through the streets.

In the middle of the chaos, however, a solemn blue barrier; two nurses dressed in their scrubs and masks, rooted to the ground. Their actions speak for themselves: “We are not OK with this.” Photojournalist Alyson McClaran captured images of the showdown between nurses and the protestors, and her photos captivated the world. It was a Tiananmen Square moment for the COVID-19 pandemic.

While Wagner wasn’t directly involved in these nurses’ stance against the protesters of the Colorado stay-at-home order, which captured news articles and headlines for the following weeks, she feels that these protesters were not considering the consequences of their message.

“I want them to be able to voice how they feel and speak up for what they believe, even if I don’t agree with it, but I think it just seems like they’re so out of touch with reality,” she said. “It’s a little hard to swallow that they so badly want things to be loosened without considering how bad it will be for health care and that then, potentially, … I’ll be taking care of them, too.”

Wagner stressed the importance of staying home during this time of uncertainty and fragility with hopes of spreading the message to be aware and cautious.

“Even if you feel great and you’re young and healthy and you hang out with other people who don’t feel sick and are also young and healthy, it can easily spread,” she said.

“You’ve got to think broad spectrum,” Wagner insists. “You hang out with one friend and that friend hangs out with someone else who sees their grandma or goes to the grocery store … you have to think of the trail that you’re leaving behind.”

She walks unsteadily behind a colleague at the hospital. No fever, no cough, she tells herself. No symptoms, no virus. A swab, a deep breath, and, later that week, a phone call. Through the careful and muffled voice on her phone, test results are delivered. Her stomach drops.

On May 6 at 10:51 p.m., just two weeks after first speaking with The Shield, Wagner sent a Shield reporter an email. It read:

“I wanted to update you and let you know I ended up testing positive for COVID-19. I’m doing OK, but it’s pretty scary, and it’s hard to know where I contracted it.”

After feeling sick for a few days and not being well enough to work some shifts, Wagner’s manager told her to check in with employee health to see if she qualified for a COVID-19 test.

“When I called [employee health], I met enough markers to be tested even though I didn’t have any ‘classic symptoms.’ But I thought, ‘it makes sense that they would just want to go ahead and confirm that I was negative before going back to work with surgical patients,’” Wagner wrote. “I never had a cough, and I never had a fever, but I did feel like shit for a few days. I just felt very fatigued and had body aches and then I started having nasal congestion and sneezing so I thought it was just a poorly timed head cold.”

And then the unexpected happened. Her test came back positive.

“I honestly was shook, like I had a stomach dropping feeling,” Wagner said. “I don’t feel like I was in denial or anything. I just really didn’t think I would test positive.”

For Wagner, contracting COVID-19 isn’t just physically straining, but emotionally straining as well.

“I also know my family is worrying about me,” Wagner said. “They’re in a different state so that weighs on me as well. I briefly had thoughts of ‘What did I do wrong that I got this?’ because I was being so careful, but I know that’s not a productive thought process, and it’s just a powerful virus, so I shouldn’t put any fault on myself.”

Fortunately, things are beginning to look up.

“Physically I’m definitely not back to normal yet, but I am feeling better than a few days ago, so I think I’m past the worst of my symptoms,” Wagner wrote on May 7. “Testing positive has definitely sparked a lot of anxiety, so I’m thankful I got the call once I had already noticed some improvements. The whole thing is a lot to process and I can’t imagine feeling worse, like I did before, and getting that news.”

Once she was able to take a step back she realized the larger lesson in her experience.

“It’s also just a very good example of how contagious it really is,” she said. “It’s even eye-opening to me because I take social distancing and lockdown orders very seriously and have gone above and beyond to be cautious at work and outside of work to protect myself and others, but unfortunately, I was still exposed.”

Soon, things will go back to “normal.” Or at least Wagner’s version of normal.

“I can go back to work 10 days after the onset of symptoms as long as I haven’t had a fever within 72 hours. I will now get 70 percent of my pay for any hours I missed after my symptoms started for up to 10 days.”

Back to the front

Twenty-four hours ago, Wagner returned to work. Without blinking an eye, she put on her gloves, mask and face shield and walked back into her COVID-dominated reality. She didn’t once look back.

Not long ago, Lindsey Wagner was a girl studying for math tests and joking with her friends at morning band rehearsals on the blacktop, a high-schooler who told the yearbook staff that lunch was the best part of her day because she could hang out with her friends, and a teen jubilantly singing the lyrics of the McCallum fight song under the lights of football stadiums. Now she wakes up each morning to slip on her mask and protect the lives of others — a first-year nurse and COVID-19 survivor putting her own health at risk in hopes of helping others.

The 15-year old girl grew up to say goodbye to the band hall and hello to both the dangers and the gratification of working each day to defeat the virus and save lives.

Wendy Stuewe • Jul 1, 2020 at 7:36 am

Great article! Thanks for highlighting nurses and my niece, Lindsey! She is a badass!

Diana Adamson • May 16, 2020 at 7:44 am

Nice work! Well written and shows a strong sense of what is going on with your source and how she fits into the world! Good work!!