In comparing pandemics, hindsight of 1918 is 2020

102 years ago, an influenza outbreak taught the world to beware a pandemic’s second and subsequent waves

May 11, 2020

The number of coronavirus cases continues to rise worldwide as governments continue to pursue a solution and civilians wait patiently in self-quarantine. In Austin, many businesses are shut down; others have turned to curbside pickup and online orders, while others still have opened their dining rooms to 25% capacity in accordance with Gov. Abbott’s April 27 announcement that partially reopened Texas businesses. Social distancing is encouraged and the stay-at-home order has been renewed.

As the world attempts to cope with a global pandemic, it is important to turn to the past in order to be prepared for the future.

A pandemic is nothing new. In fact, the world has dealt with them steadily since the Antonine Plague in 165 C.E. with a death toll of 5 million, according to MPH online. The Black Death, which ravaged the world from 1346 to 1353 C.E. and produced a death toll of between 75 and 200 million, continues to be regarded as one of the greatest tragedies in human history.

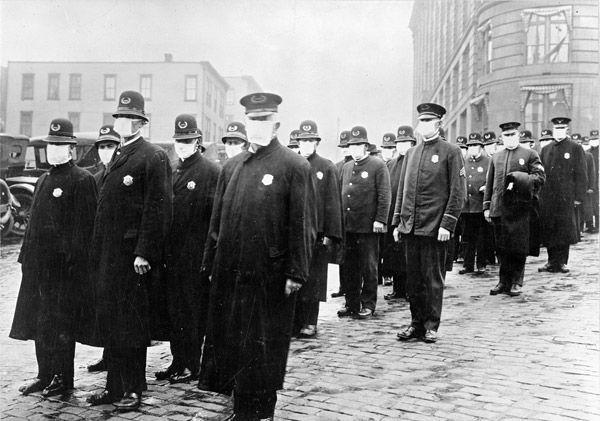

Most recently, the world was faced with the influenza pandemic of 1918, better known (inaccurately by the way) as the Spanish Flu. Revisiting the 1918 pandemic provides valuable insight into how societies have reacted to pandemics historically and what consequences have resulted from those reactions. Studying the 1918 pandemic can help us avoid the mistakes of the past and be better prepared to face COVID-19.

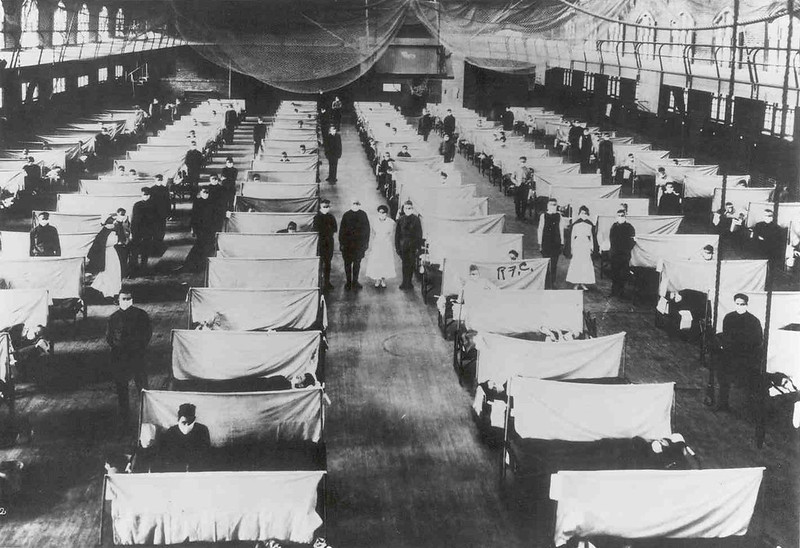

Historically, societies have struggled to treat and control the spread of pandemics. In 1918, medicine was much less developed than it is today, and sanitation was much poorer. Governments had fewer resources to put toward the effort to control the spread of influenza.

“The big cities were very, very crowded in working-class areas,” said Jeremi Suri, a history professor at the University of Texas, “and people lived in very unsanitary conditions, and they did not understand germs in the way we do today. So it was much harder for people to keep clean, and it was much harder for them to socially distance.”

On top of that, World War I consumed the focus and energy of world leaders. Soldiers were being dispatched all over the world, and the global travel required to stage a war greatly contributed to the spread of influenza.

“World War I was what actually was the main mechanism by which the virus spread,” Suri said. “It started in Kansas, it was called the Spanish Flu only because Spain did not have censorship of its news coverage. It was censored in other areas. But it started in Kansas, it spread to Europe on a military ship, and then it came back. So, it was spread by the war.”

World War I didn’t just spread the 1918 influenza, it hindered the ability of countries to respond to the crisis. According to Kristen Wachsmann, a McCallum AP World History teacher, the war overwhelmed world governments.

“Because the Spanish Flu outbreak occurred during the end of World War I, I think the world was uniquely under-prepared to respond to the crisis,” Wachsmann said. “’The Great War’ taxed countries’ finances, infrastructure, people and morale. While a pandemic is always difficult to manage, the historical context of war made it much worse.”

In Austin, the first influenza case was reported in the Camp Mabry barracks on Sept. 27, 1918. It quickly spread, multiplying to 900 cases within a week, according to The Austin American Statesman. On Oct. 8, acting governor, R.M. Johnson, prohibited all social gatherings.

When the first coronavirus case in Travis County was reported on March 12, the city of Austin took much less time to respond. The very next day, Austin ISD canceled school and people began to self-quarantine. This quick response is likely the reason that a week after the first case was reported, there were only 58 coronavirus cases in Travis County, according to the City of Austin website.

The quarantine in October 1918 lasted for about a month before the ban was lifted. During that time, many local businesses suspended their activity. Most of those businesses are gone now, but a few still-standing local businesses lasted through the Spanish Flu in 1918, including the Paramount Theatre, Avenue B Grocery, and Scholz Garten. Suri explains that although it was a strain to have local businesses closed down, the lifestyle back then was more accommodating to the self-sufficient aspect of a quarantine.

“Austin was a smaller, more rural community at the time,” Suri said. “So, many people in Austin at that time were not as dependent as we are today on food from grocery stores and all sorts of other things. People were actually a little more self-sufficient. Their lives were disrupted, but they tended to feel a little less in peril, a little less at risk at the time because the city was less dense and people were a little more self-sufficient.”

Today, in the era of COVID-19, conditions in Austin are more severe due to the density of the population. In the last 100 years, Austin’s population has grown from 34,876 in 1920 to 926,426 in 2016, according to the U.S. Census Bureau and the City of Austin. In the metro area, the population is estimated to be over 2 million in 2020.

Due to the size of this population, health experts estimate that the quarantine will last four times longer, with many experts speculating that the quarantine will be lifted in the summer before returning in response to a second wave in the fall. At present, Gov. Abbott is slowly allowing businesses to reopen to partial capacity, while Mayor Adler and Judge Eckhardt extended the stay-at-home order to the end of May for Austin and June 15 for Travis County.

On April 24, Prof. Suri predicted that restaurants would be the first to open, which was proven correct on April 27 when Gov. Abbott announced that restaurants, among a few other businesses, could open to 25% capacity. Prof. Suri also predicts that a second wave in the fall will bring more closures.

“I don’t think we’re going to have football games, but we’ll probably be going to restaurants and things of that sort,” Suri said. “The libraries will open. But we have to be prepared for other kinds of closures thereafter because you get a second wave, usually in the fall, from the disease, and we’ll see it go up and down.”

The first wave of the influenza pandemic occurred in the spring and summer of 1918 and passed over Austin without incident. However, it was the second wave in the fall that hit the city hard. This pattern of the second wave being more lethal was true nationwide. Although the underdeveloped methods for reporting disease makes it hard to tell how many people died in each wave, it is evident that the second wave was most lethal in the U.S., according to the CDC.

A possible reason that the second wave was more lethal in 1918 is that not enough precautions were taken during the first wave. Wachsmann believes that by opening up the state of Texas too soon, a possible second wave of COVID-19 could be more lethal than the first. Gov. Abbott’s decision to steadily opening Texas back up again to partial capacity could be harmful to Texas.

“I think that Gov. Abbott opening the state of Texas against the advice of public health experts could make a second wave more significant,” Wachsmann said. “In terms of the outbreak, Texas’ percentages seem relatively low compared to other states like New York and New Jersey. This could be a reflection of many things including size of urban centers, population density and access to testing. It is possible that Texas’s low numbers are a false comfort to leadership and the general public. I am concerned that this false confidence will put more people at risk moving forward.”

Dr. Mark McClellan of Duke Medical School is on Gov. Abbott’s team of medical experts advising him on how best to face COVID-19. He believes that this virus is a reminder of our vulnerability as a society to disease, even in the era of modern medicine.

“Even if most people get vaccinated, you sometimes have to get booster vaccines after a while, and sometimes the vaccines don’t work,” Dr. McClellan said. “So I think we’re going to have to be careful for a while about this virus, and I think this is a good reminder that there are viruses that come along, we’ve had previous epidemics like SARS and H1N1 Flu, both of those happened within the last 20 years, so I think we need to be more careful to prevent something like this in the future.”

Prof. Suri shares the sentiment that we must acknowledge our vulnerability to disease. He explains that in the modern era, humans tend to believe that the passage of time has made them less vulnerable, and this mindset can be very harmful.

“I think what we’re learning with the coronavirus is that even with all the medical capabilities we have, a virus is still a very powerful thing,” Suri said. “We should not believe, as we might have believed 10 years ago, that we, as human beings, have conquered viruses; we have conquered pandemics. … That’s what we call the Hubris of Modernism, thinking we’re so much better today than we were before.”

Suri believes that this hubris can be especially harmful in young people, who can become carriers if they are not careful to take the proper precautions and socially distance. He explained that the influenza pandemic in 1918 proved most lethal to young people in their 20s because of a lack of pre-existing immunity. Now, the coronavirus is proving to be more dangerous for elderly people, but the danger young people were once in must not be forgotten, Suri said.

“Students want to be careful that [they] don’t become carriers of it to [their] parents and grandparents,” Suri said. “And that’s the point I often make to my students at the university. Don’t be complacent about [the spread] because even if you get it and survive, you then pass it on to others. People who are older, particularly in your family, they’re the ones who could really die from this. And so you have to think about not just your own health, but the health of others and the risk you expose others to today if you become a carrier of this virus.”

Today, leaders like Abbott must make some important decisions on how best to protect the safety of their citizens. During this time, it is telling to look back at how the city of Austin and the world handled a pandemic 100 years ago. Some things, we can improve on, and others, we can learn lessons from that we can put into practice as the world continues to grapple with this global crisis.

–with reporting by Anna McClellan