Austin’s Berlin Wall: A Look at I-35

Getting Nowhere, Fast: A view from above the 51st Street bridge over North Interstate 35. This area is one of the key bottlenecks on the highway, with a fly-over merging with the road. This causes terrible back-ups around this area. Downtown Austin can be seen in the far distance, the heart of the city.

October 2, 2019

It doesn’t take a genius to see that the interstate system in Austin has completely and utterly failed. Interstate Highway 35, known as I-35 or “the Berlin wall” locally, is a shining example of how a road can completely kill one’s Monday morning. Not only is this concrete abomination riddled with sections of poor road, aging infrastructure, and terrible traffic, it was used to racially divide the city in the 1920’s. It not only induces skin-crawling rage on its bad days, but stands for a time when the city was completely segregated even when traffic is more manageable.

First, let’s discuss the traffic. Ask just about anyone who goes to McCallum, or really anyone who lives in Austin, about traffic on I-35 and you’ll get a response clear as day: it sucks. I live just East of the beast, and I have to drive on the access road or the highway itself nearly every day. I have summarized my few years of driving and being driven on the highway into one word: agony. From around 8-10 in the morning and 4-6 in the afternoon, I would recommend keeping a 100-yard radius of the highway unless absolutely necessary.

Traffic is backed up for miles at a time, and essentially turns into a parking lot. According to KVUE News, the stretch of highway that runs through Austin is the third most congested highway in Texas. Then there’s the matter of infrastructure, or should I say, lack thereof. Just last month in August, there were reports of pieces of the upper deck of I-35 falling down. It was literally raining concrete. APD officials later claimed that this was not the upper deck, but even if it wasn’t, where is the concrete coming from? The sky? I digress.

Stretches of the road vary from being decent to absolutely terrifying to drive on. The highway seemingly narrows near the Caesar Chavez exit, paired with a relatively sharp turn, creates a bottleneck right before the bridge. This is one of many ground zeroes, where the highway’s design flaws are abundantly apparent. In addition to this, there are the driving habits of many people in Austin. Many people tend to not let anyone into their lane at all costs, perhaps a neanderthalic instinct left over from our ancestors. Not only will many not let you in, but I have also been almost rear-ended by drivers who are so focused on not “losing their spot” that they speed up as you change lanes to try and stop you. If you happen to be one of these drivers, I have a very basic question to ask: why would you want to not let others in if you’ve already allowed for enough space for one, two, or in some cases, three cars?

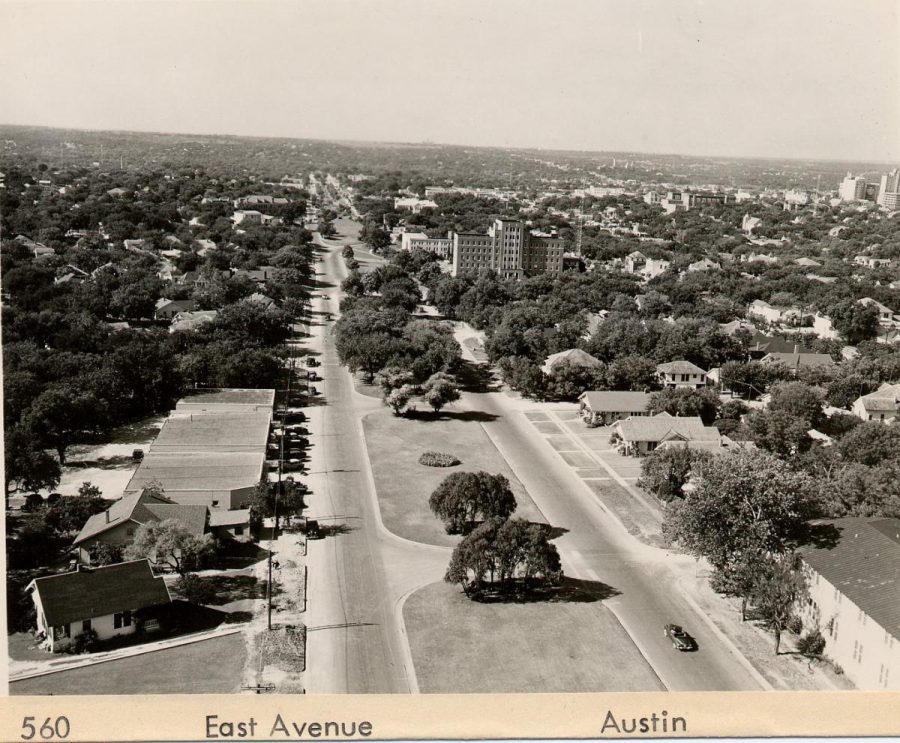

We have established that I-35 is a driving nightmare, but what about its history? Some would be surprised to learn it has a disturbing and divisive past. The highway, once called East Avenue, was at one point a very clear wall, separating the historically poorer black and brown communities from the wealthier and more affluent white ones. East Avenue, according to KVUE News, was designated by the city plan in 1928 to segregate these communities. Work on the highway began in the mid 1950’s, finishing in 1962.

As someone who lives just east of the highway, this dichotomy for the most part is true, although with skyrocketing housing prices and gentrification, it has become less of a home for these communities. It is increasingly the case now where long-standing Austinites must move to the suburbs in order to accommodate exorbitantly priced condominiums or modern houses, which could not stand out more from the area’s architecture. I contend that even though the city’s segregationist policies have long since been disbanded, I-35 still represents further disenfranchisement of an already deprived community.

It no longer, however, an explicit town policy or spelled out in any affidavit, but instead disguised in development companies’ contracts and the city’s laissez-faire approach to regulation. Although Austin has been a blue dot in a red sea politically and socially, the massive concrete structure serves as a reminder of the mistakes made by the generations before us. The highway should remind us to understand how much influence one structure can have on the community around it. In these ways, I-35 can be a positive thing, but only until you have to drive on it.