Whether it’s a buzzing noise from your pocket or the lit-up screen illuminating your backpack, if you own a cellphone, you have probably been distracted in class at some point this school year by your cellphone. You’re sitting in class when you get a notification on your phone. You fight the urge to check it and risk having it confiscated by a zero-tolerance teacher. It seems like no big deal to just check it once, but your teachers don’t feel the same way. Teachers all over the country are fighting the ongoing cellphone battle; the McCallum staff is no exception

“[Phones] just take attention away from what’s going on,” business and accounting teacher Michael McLaughlin said. “I mean, it could be three kids, it could be half the class who are subtly doing something with their phone or thinking about their phones, and if I’m trying to explain something, they’re not hearing a word I’m saying.”

Some teachers have strict policies to restrict or eliminate cell phone use, while others are more laid-back. Certain classes might not require a strict policy for phones; like art, for example, where students often listen to music to relax and channel their creativity. Some classes, however, require a student to read or work on something, in which case teachers believe music could be distracting.

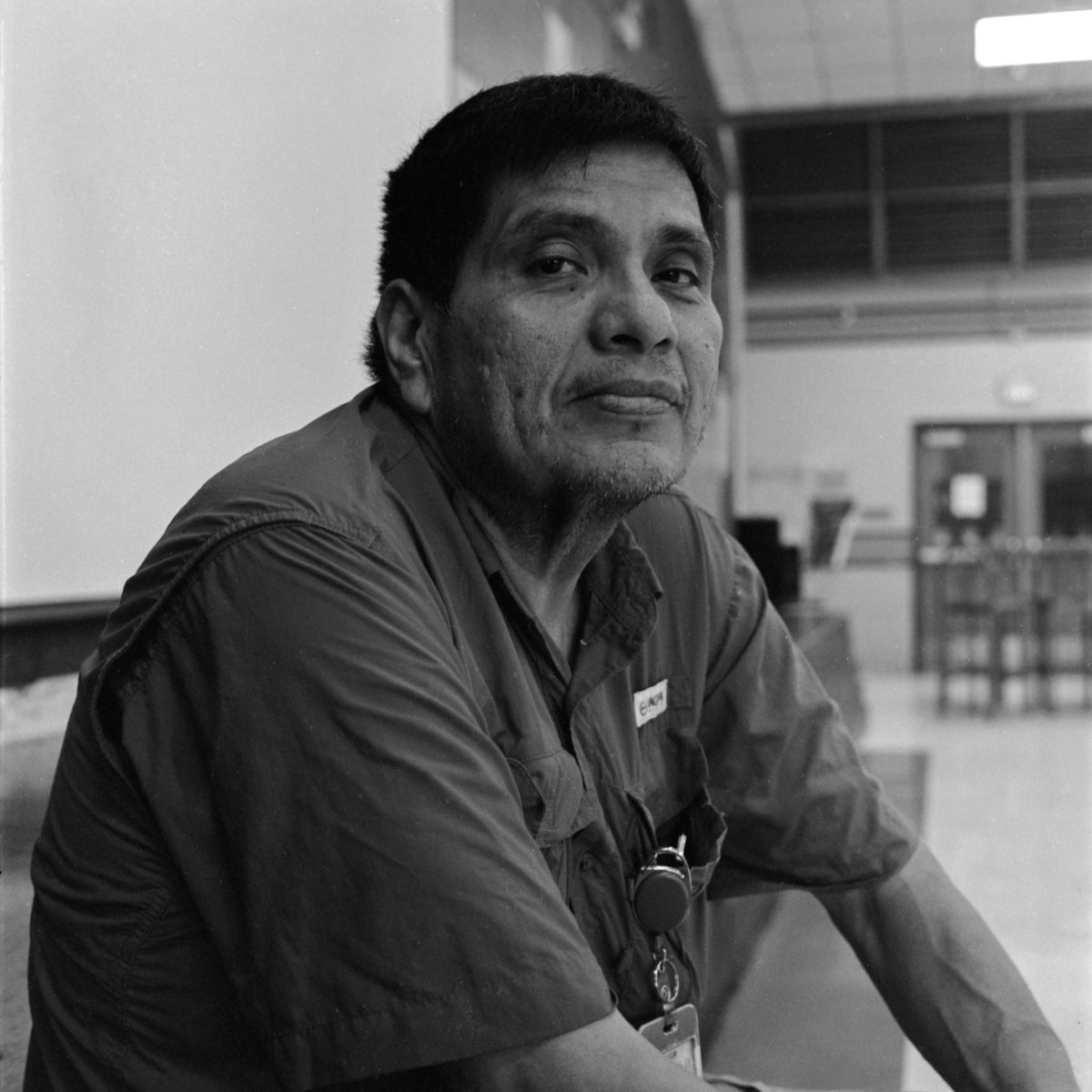

“Many students want to listen to music, and it’s hard for them, because they feel that listening to music helps them focus, but I would argue that that’s not backed up by any scientific research,” history teacher Clifford Stanchos said. “If you’re listening to Eminem in the background, that’s not going to help you; it might just be a coping mechanism for you to ignore [your work] and focus on something else.”

Other teachers have different policies for music. Social studies teacher Michael Sanabria allows music in his classroom, but everyone must listen to the same songs. He says he is against individual music with headphones in his classroom, because it disconnects his students.

Therefore, he asks his students for suggestions, and the first person to raise their hand gets to choose. He then plays the song through the speakers so everyone can listen. He says he believes music’s sole purpose is to bring people together and affect their frame of mind in some way.

“We know that music does impact [a person’s] mood, and it alters your emotional state. so [with headphones] you end up with a [space] full of people who are all experiencing different emotional states, and it ends up being really disconnected,” Sanabria said. “In my classroom, I don’t want to have that, so when we listen to music, I would rather all of us listen to the same music so we’re all having a shared experience.”

Core classes typically require students to listen to their teacher for an extended period of time, which can be hard for some. The lure of cellphones may sometimes prevent a student from listening attentively, and they’ll end up taking it out during class. It might seem like just one student isn’t going to do any harm; however, according to teachers, one student leads to two and then three, and then half the class. Seeing another student on their phone both distracts and tempts others. Because of this temptation, many teachers have a no-tolerance attitude about cellphones; some teachers even collect phones at the beginning of class, while others might trust students to keep their cellphones stored during class.

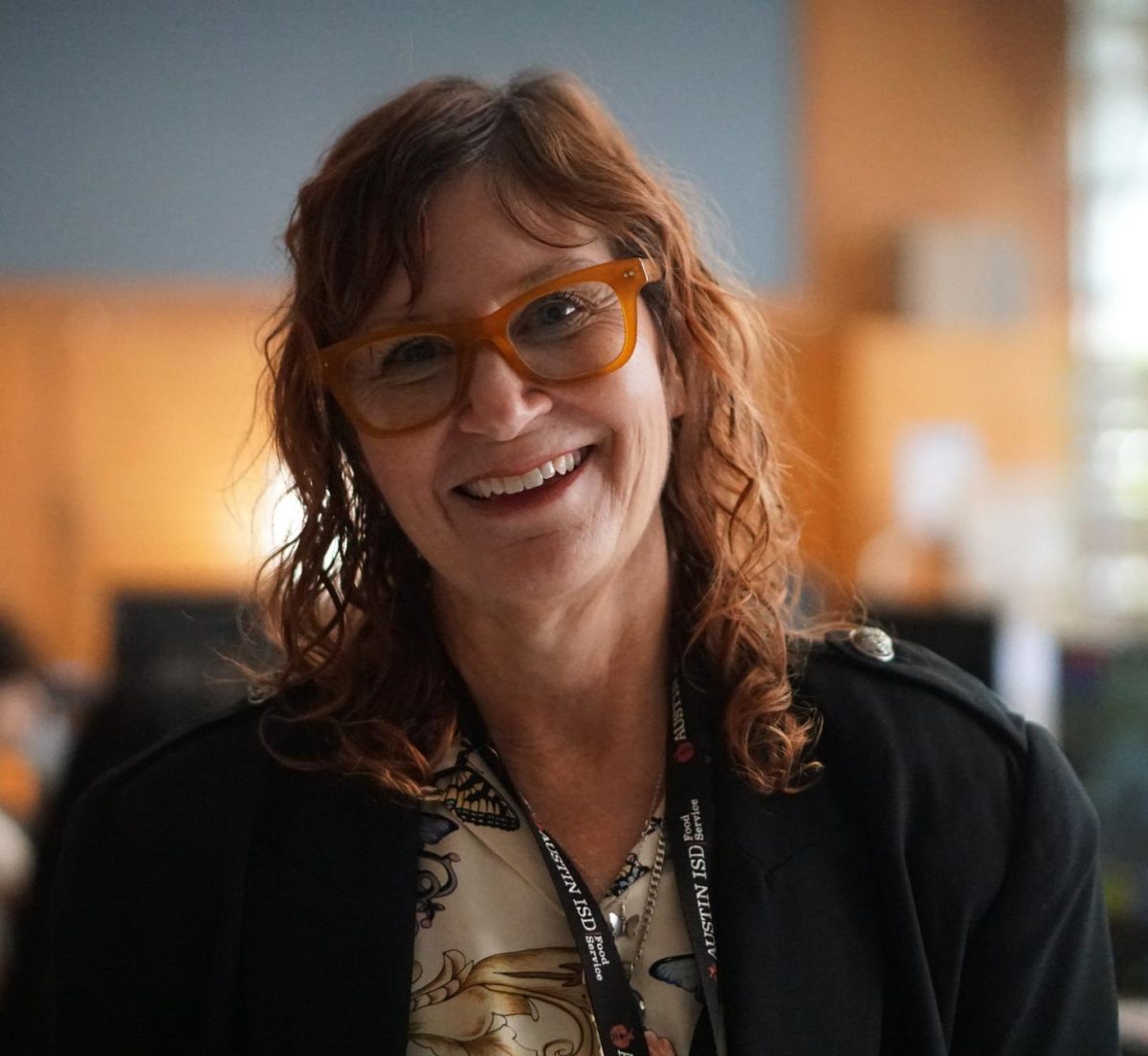

“I think that there’s a time and place for everything, and I don’t think a learning environment is a time to be distracted by a cellphone,” English teacher Diana Adamson said. “I think they’re problematic, [and] I think we’re becoming more and more like Fahrenheit 451, attached to something all the time.”

Teachers’ policies can depend on the subject, the dynamic of the class and the teachers’ preference. Some said they change their policy from year to year to see what works. At one time, Stanchos said he had a policy that relied on trust with the students. It was up to them to have self-control and know that his class wasn’t the time for a cellphone. He then changed to having students put them in a bag at the end of the desks, but now he has the students put their phones in a shoe-holder at the front of the classroom at the beginning of class everyday and take them back at the end.

“I find that the shoe-holder removes the conflict,” Stanchos said. “The less you are actually in touch with the phone, the less likely you are to rebel against, say, being asked to give the phone up.”

He believes attempting to eliminate the problem altogether is the way to go, saying that it minimizes class distraction.

While Stanchos’ policy has changed from year to year, Adamson’s changes her policy from class to class. She says she has found that freshman, being the youngest and newest to high school, need to be controlled more.

“I think [it’s OK,] as long as [phones] don’t come out when they’re not supposed to come out,” Adamson said. “They’re supposed to be in the baskets [that are on the tables] for my freshman. For my upperclassmen, if I see them, I’ll treat them just like the freshmen, and they have to give them to me until the end of the day.”

She said that while there have been some problems, she finds that upperclassman are more responsible with phone use and can control when they choose to use them. Therefore, they get to keep them as long as they are responsible with them while freshman must put them in the basket. McLaughlin’s policy is not much different, but he has some different reasoning behind it. His policy was absolutely no cellphones, and if he sees one, he’ll take it. It has changed slightly; he now usually collects the phones in a bucket at the beginning of class. He says he believes cellphone use negatively affects teenage mental health; therefore, he doesn’t allow them in his classrooms.

“My big concern really is the correlation between screen time and teenage depression, [because] if you look at some studies recently, teenage depression has just gone through the roof at the exact same time that cell phones became popular,” McLaughlin said. “People should be [very] alarmed about that.”

While not every teacher has a strict policy on cell phones, many argue that cell phones, when not used properly, can be distraction and extend the amount of time it takes for a student to complete their work. There’s no doubt that they can be helpful and even necessary in certain situations; however, taking a cellphone out in class when not asked to can be a dangerous game to play. The best rule to follow is to respect a teacher’s policy and ask if you have any questions about it instead of assuming so as not to have it confiscated.

“My job as an educator is to ensure the education of all students, not just those who can multitask or who can set it aside and get work done,” Stanchos said. “And the best way for me to ensure an education for all students is to just across the board, not allow the phone.”

Selena Dejesus-Leyva • May 2, 2019 at 11:28 am

As a student who uses my phone a lot during class, it would kill me if i had to put my phone away during class. I do all my work and listen to music while doing it. My grades are good and if u see me in a class i’m usually listening to music busting my ass off to do my work. besides the whole thing that Mr. Sanabria said about everyone listening to the same music isn’t a good idea because not everyone has the same taste in music. Also what if your family is going through a crisis and the only way to stay informed is through social media or something. kids need their phones at all times. That’s my opinion.