They run around unseen, unrecognized, in the darkness. They’re always there, waiting for something to go wrong, waiting for a change. They work tirelessly, rarely stopping, sacrificing everything to finish what they start.

Behind every show at McCallum High School are the technicians. They build the sets, make the costumes, and design the lighting. Working upwards of 18 hours a week and up to 13 hours a day, these dedicated students work not for the fame, not for the pay, not for the thrill of performing, but simply because they enjoy what they do so much. To them, it’s worth their grades, social life, and a stress-free life.

“You gotta really enjoy doing what you do for doing it,” sophomore Dashel Beckett said. “Not for anyone else, or for the recognition you’re going to get, just doing the tech because you enjoy doing tech.”

And they do.

At 42nd Street tech call, MacTheatre’s musical that premieres on Jan. 31 at 7 p.m. and runs through Feb. 10, technicians laugh and talk with each other while working, even if it’s hard, due to the fact that they are lacking lumber and an adult or teacher at rehearsal. Although mainstage shows can be stressful at times for many different reasons, they’re also a lot of fun, according to junior technical theatre major Zoe Griffith.

“You’re with all of your friends and everyone’s just doing their best,” she said. “It’s fun helping showcase [the performers] since we have such talented students at our school.”

During these tech calls, technicians work on projects within their individual strand for their show, which corresponds most of the time with an student’s specialization. At McCallum the five strands are: scenic, props, lighting, sound, and costumes. For this show, Griffith is co-lighting crew head and designer with junior Graham Protzman. 42nd Street will be both of their ninth mainstage shows at McCallum, so they know firsthand how much work goes into a show.

“It’s mentally and physically challenging,” Griffith said. “I don’t think many people know how serious technical theatre is and how much training and work goes into it.”

The scenic crew works on various aspects of the set during rehearsal. The show features seven wagons that rotate and roll on and off of the stage to create different scenes and many backdrops. Photo by Caleb Melville.

The build for 42nd Street spans three months, with planning happening as early as the year before. The technical directors and all of the crew heads from different strands of technical theatre have to collaborate with the director in order to make the director’s vision a reality.

Lighting designers like Griffith and Protzman have to draw up lighting plots; select angles, effects, and colors; and hang, focus, and program each individual light. During Starmites, MacTheatre’s fall musical, this had to be done for more than 400 lights.

Collaborating incredibly closely with the director, costumes crew heads have to rent, buy, find or make hundreds of costumes for each show, each of them specific to every single actor. This is especially a challenge for the upcoming show due to the sheer number of costumes for every ensemble member.

Scenic crew heads must create blueprints for the set pieces, choosing dimensions, types of lumber and hardware, and paint colors. During the build, their crew must follow these plans incredibly closely at the risk of having to start over.

Sophomore Emma Lindsey, Viv Osterweil and freshman Sophia Lindsey-Boeck work on measuring fabric for costumes. Costumes crew is in charge of not only the costumes for the show but also the wigs. Photo by Caleb Melville.

Props crew must build, find and buy or rent dozens of different kinds of props, from anything to a vintage telephone holder to a ten foot “telepod.” For 42nd street, they are building a multitude of giant dimes that ensemble members will dance on during the number “We’re in the Money,” one of them six feet wide.

During the show, each sound crew member has to pay incredibly detailed attention to how it sounds. They must “mix the show” and trigger sound effects live because timing and the intensity of the actors’ voices varies night to night.

“It’s a lot harder than it looks,” Protzman said.

All strands of technical theatre involve detailed planning and execution of those plans. It’s incredibly time-consuming, and it takes a toll on the technicians. Both Griffith and Beckett agree that working a show takes time away from other important things, like homework and family, especially as it gets closer to tech week, or the week before opening night of a show.

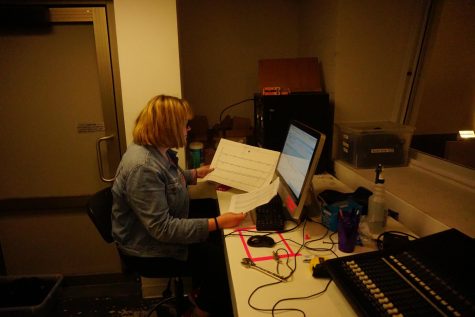

Junior Zoe Griffith looks over the lighting plots for the show in the booth of the MAC. Griffith is co-designing the lighting for 42nd Street with junior Graham Protzmann. This is Griffith’s second show she has designed for, her first being spring straight play 44 Plays for 44 Presidents. Photo by Caleb Melville.

“Tech week is literally just eat, sleep, grind,” Beckett said. “You don’t have time for anything.”

Griffith agrees.

“I often don’t see my family until a show is done, from tech week leading up to the end of a show.”

Rehearsals can extend far into the night, sometimes even lasting 13 hours, starting at 9 a.m. and and ending at 10 p.m., according to Protzman. Because of this time commitment, technicians often learn better organization and time management skills. Despite the long hours and hard work, they find shows incredibly rewarding, especially when the show is put on for an audience and the cumulation of all their hard work is finalized and shown off.

Technicians, however, are needed for more than just plays and musicals. Technical theatre majors also have the option to work “special events,” which include dance shows, choir performances, the fashion show, the Fine Arts Academy showcase and more. These events differ from MacTheatre’s shows because they are a lot faster-paced and less structured.

“You have a lot more independence and responsibility on yourself,” Griffith said.

The students make more of the design decisions than they would when working a mainstage show. They also get paid, which is one of the perks of working an “freelance” event. Plus, these students have the opportunity to interact with students and teachers from other fine arts strands at McCallum that they normally wouldn’t interact with on a daily basis.

Working both shows and special events are very different than technical theatre class during the school day, for both majors and non-majors. According to Beckett and sophomore technical theatre major Vivian Osterweil, technical theatre class, especially this year, is taught in hypotheticals, rather than working hands-on like it is done during shows.

“Tech class, it’s basically theory,” Beckett said.

When Griffith and Protzman were freshmen and sophomores, they focused on training and projects for hypothetical shows in their tech classes. But even though a class is dedicated to teaching technical theatre, most students still learn more actually working a show than they do in class.

“I feel like that’s when you can learn the most,” said Protzman, “because you can learn a lot of situations that would happen.”

Beckett agrees, saying “I learned less in my first semester of tech class than I did in my first two weeks of West Side [Story].”

During the first few weeks of a show, students also learn whether they enjoy technical theatre enough to continue with it simply because they enjoy it. It’s time-consuming, and receives little recognition, according to sophomore technical theatre major Vivian Osterweil.

“There’s like that one little hand wave that the director gives at the end.”

“If you’re lucky,” Beckett added. Despite this lack of recognition, Osterweil said that the fun and satisfaction of putting on a show makes it all worth it. Technicians are a crucial part of any performance, whether they’re given the appreciation they deserve or not. But they don’t mind.

After all, Osterweil said, “Without us, there would just be naked people on a stage, like, yelling. That would be it.”