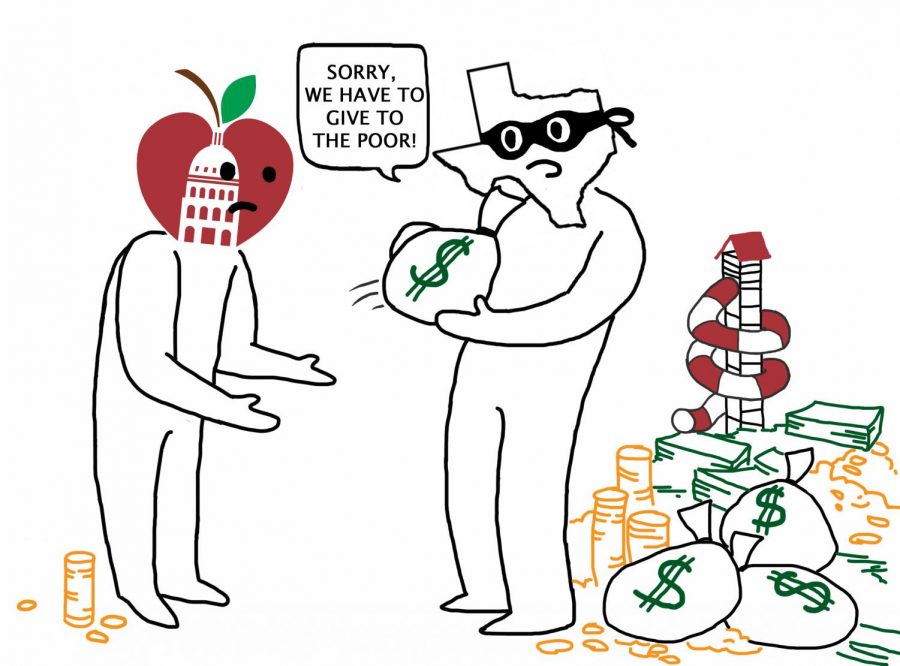

We have all been Hood-winked

Since the Robin Hood plan began in 1994, AISD has paid more than $3 billion into the program.

December 27, 2018

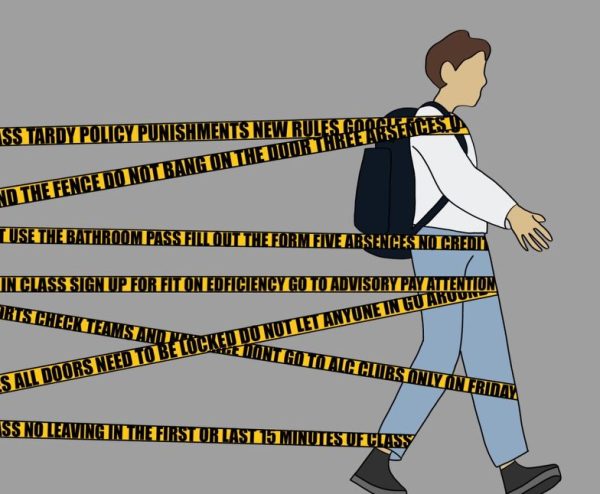

As most of us know all too well by now, the Austin Independent School District faces a budget crisis that prompted a district task force to discuss eliminating or retrenching expensive special programs such as our beloved Fine Arts Academy. While the Academy has been declared safe from cuts, there is still fear of other proposed cost-saving measures: teachers losing one of their planning periods, increasing class sizes, redrawing district boundaries or even consolidating or closing campuses altogether.

AISD estimates that in 2019 it will ante up $669.6 million to the state to be distributed to other districts. By 2020, there is an anticipated increase of another $115 million due to a reassessment of taxable property.

Instead of blaming AISD money management or public school funding in general, we must focus on the real reason for this budget deficit.

Usually high property values are a good thing for school districts because most school funding comes from property taxes. The reverse, however, is true in Texas. In an attempt to balance out school funding between richer and poorer school districts, the state legislature created the “recapture” program, commonly called the “Robin Hood Plan.” In theory, the system fairly distributes wealth more evenly across the state. In practice, however, the system has over-corrected the issue, siphoning off a disproportionate amount of money from so-called “wealthy” districts to less property-wealthy school districts.

The Robin Hood plan was never intended to be taken this far.

On May 23, 1984, Edgewood ISD, just outside of San Antonio, reported that their district was struggling while their neighbor, San Antonio ISD, enjoyed vastly more funding. The issue went to court in a case called “Edgewood v Kirby,” where the court decided that the property tax method of funding schools was unconstitutional. It gave more money to rich, urban regions throughout the state, neglecting poorer rural schools. Created in 1991, the Robin Hood plan sought to ensure equal-opportunity school districts statewide by collecting money from property-rich regions and distributing it evenly across the state. The goal was to have a relatively even amount of money spent per student in each district.

The Robin Hood plan’s impact had been evident in our longstanding facilities issues: leaky windows, broken air-conditioning systems, and pest infestations.

The results, however, have been anything but equal. According to data collected by NPR, the western half of the state, the one with fewer property-rich cities such as Austin, has a greater budget per capita, and the disparity is rising every year. In many cases, rural west Texas districts receive more than 33 percent of the national average. In Austin and other large cities, such as Dallas, Houston, and even Amarillo, however, the percentage is significantly lower than the national average.

It can be argued that because these urban cities have such high populations, the cost of operating a school is lower per student than it would be in districts with a smaller student body. In large districts such as AISD, however, there are many schools to account for, each of them needing teachers, custodians, officers, counselors, and all of the expenses that go along with keeping a school running. In AISD alone, the same percentage of money made from property taxes is sent to the state in recapture funds as is used for teacher’s salaries (46 percent). The rest of the money (8 percent) is spent on professional services, supplies, and other operational costs.

AISD estimates that in 2019 it will ante up $669.6 million to the state to be distributed to other districts. By 2020, there is an anticipated increase of another $115 million due to a reassessment of taxable property. In total, even since the beginning of the Robin Hood plan as we know it in 1994, Austin ISD has poured more than $3 billion into the program.

Abolishing the Robin Hood plan is likely out of the question, but it can and should be reeled in.

This is not acceptable. That money could be used to fix up our old buildings, raise money for extracurricular activities or purchase new materials for teachers. There is no way that rural districts should have resources to spare while McCallum is having to make major cuts to our funding. Even though the Fine Arts Academy is no longer a possible budged casualty, major changes are still likely to happen affecting next year’s bell schedule, available classes and teacher schedules.

Even though the effects of the Robin Hood plan have not been widely understood until the Fine Arts Academy closure scare, the plan’s impact had been evident in our longstanding facilities issues: leaky windows, broken air-conditioning systems, and pest infestations. It’s time for the way Texas regulates our budget to change.

Abolishing the Robin Hood plan is likely out of the question, but it can and should be reeled in. If the state reduced how much AISD pays to other districts by 1 percent ($5.44 million) every year for the next couple of years, it could significantly reduce the disparity between rural and urban school funding. If we can find a balance between providing for property-wealthy districts and sending extra money to property-poor areas, the real intention of the Robin Hood Plan can be fulfilled.