Let the present take the precedent

Texans can remember their past, but should not be defined by it

January 8, 2018

Five schools in the Austin Independent School District are facing the repercussions of the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va., that cost a life on Aug. 12. Shock waves were sent throughout the country, prompting the removal of monuments and buildings with Confederate connections.

AISD Board President Kendall Pace tweeted after the August rally, “Schools named = monuments. The time is now.”

The Allan Facility (formerly Allan Elementary), Fulmore Middle School, Lanier High School, Reagan High School, and the Johnston campus are all named after men who fought or supported the Confederacy; Allan after an officer in its army, Fulmore after a private, Lanier after a poet and soldier who fought for it, and Reagan and Johnston after generals.

AISD has only seen this action once before, in May 2016, when the school board voted to rename Robert E. Lee Elementary to Russell Lee Elementary after a Depression-era photographer.

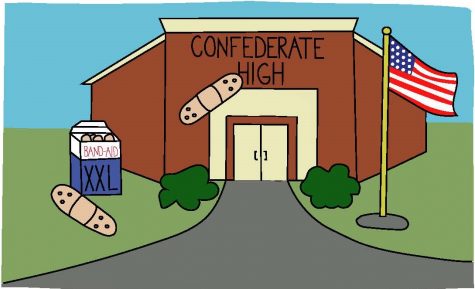

Schools being renamed because of their Confederate ties have shown us that a school’s identity and its community are strongly aligned. Every school that might lose its Confederate name has a student body composed more than 75 percent of minority populations. To have to step into a school every day, walk by countless signs and statements of school pride, all which revolve around a historical figure who fought for the Confederacy, can be stifling to anyone, especially to students of younger ages who have only recently become aware of the stances for which those people fought. Every student deserves to attend a school named after someone they can look up to, and any Confederate is not that person. We are not for continued prejudices or misplaced “Southern pride,” but at the same time, renaming schools is a Band-Aid solution to a much more deeply rooted issue.

Dedicating a building to someone, especially a place of education, is no small deal. It calls attention to them in a permanent manner, elevates their status, and envisions them as a role model; people who took part in the Confederacy do not deserve that attention. These names send the wrong message to communities surrounding Austin: the idea that the actions and prejudices of these people have left an impact on our community and continue on in tradition and legacy.

Those against renaming the schools argue that there is too much unnecessary cost. They don’t see the names of the schools as having any significance, and to them the idea of renaming them seems wasteful, because the cost and energy spent changing signs and other decorations could’ve been used better elsewhere.

Although there is validity to this argument, renaming the schools would not be the one and only change made. If that were the case, there would be slim lasting benefit from the somewhat hefty costs. Removing the Confederate names would break the surface of a much deeper issue, enabling the school district and Austin in its entirety to discuss and make way for more lasting, meaningful change. To truly see benefit from the name changes, it would have to be the first step of many.

The possibility that replacing these names would open doors to resolve issues that remain in present day Austin is not something that should be shrugged off. In the way that the Hollywood sexual assault allegations put controversy in center stage to encourage more action, this first step could prompt us to tackle deeper issues embedded in AISD.

The current names spread ideals of intolerance, discrimination, and narrow-mindedness. This is not what we want to associate our schools with. These people are not who students should look up to. Wiping the names away could offer a larger, more supportive platform to put programs in place and ideas that benefit Austin schools in the long-term. Simply changing the names and moving on, however, would do nothing for the schools or the students themselves.

Jazzabelle Davishines • Jan 23, 2018 at 11:42 am

There are ways to observe and learn about important historical figures without honoring them, and thereby condoning their actions.

Bella Russo • Jan 19, 2018 at 2:37 pm

This story is polished and collected, and the respectful debate is something to be admired in all opinion stories. The issue is also very timely considering the impending change, not only to the schools confederate ties, but to the under the surface issues theses changes will bring light to. It also brought up some points and counterpoints that I had not thought about previously.

Erica Moomaw • Jan 19, 2018 at 2:06 pm

I appreciated how the argument was reasonable and both sides could be seen fairly, while still emphasizing the need to change school names because of association.