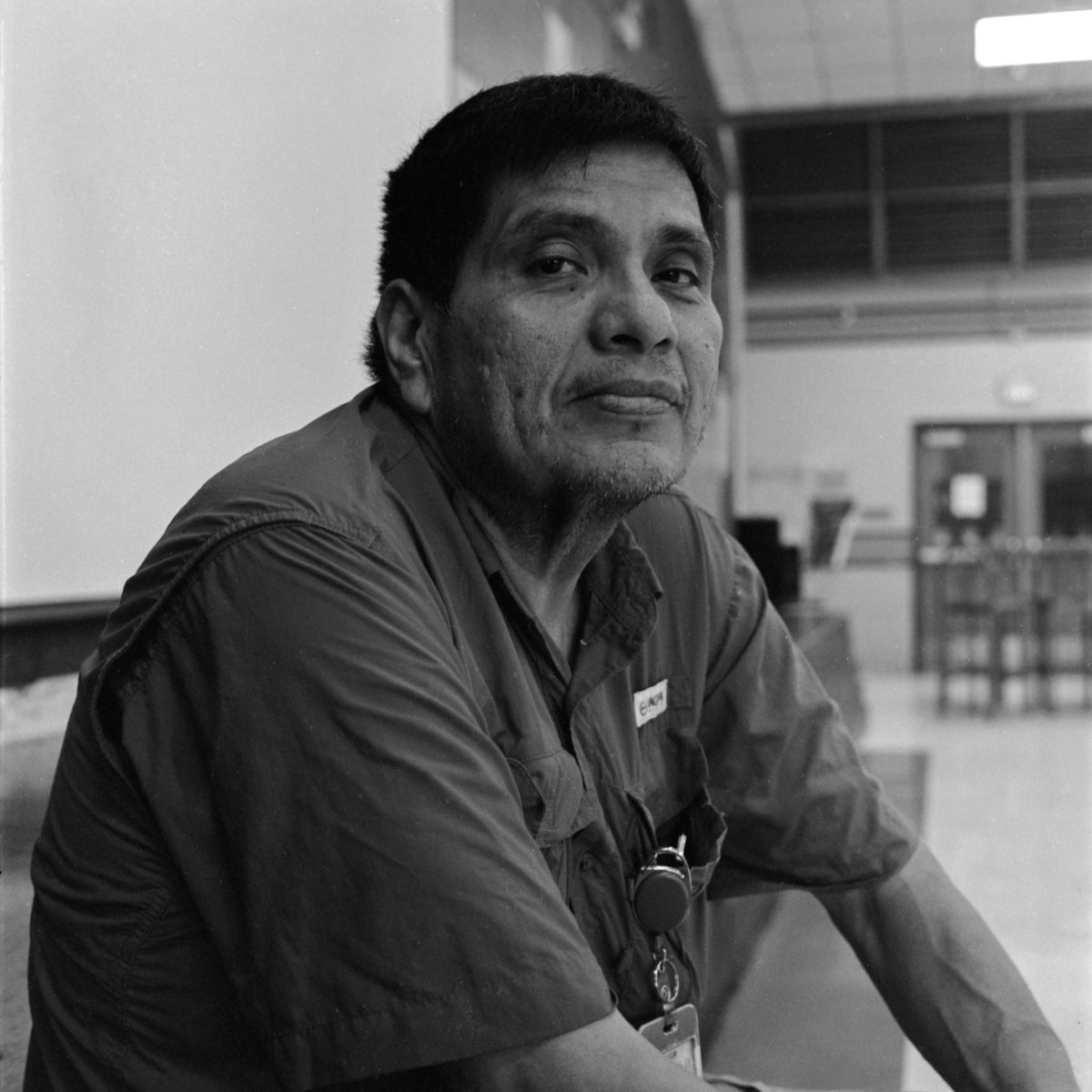

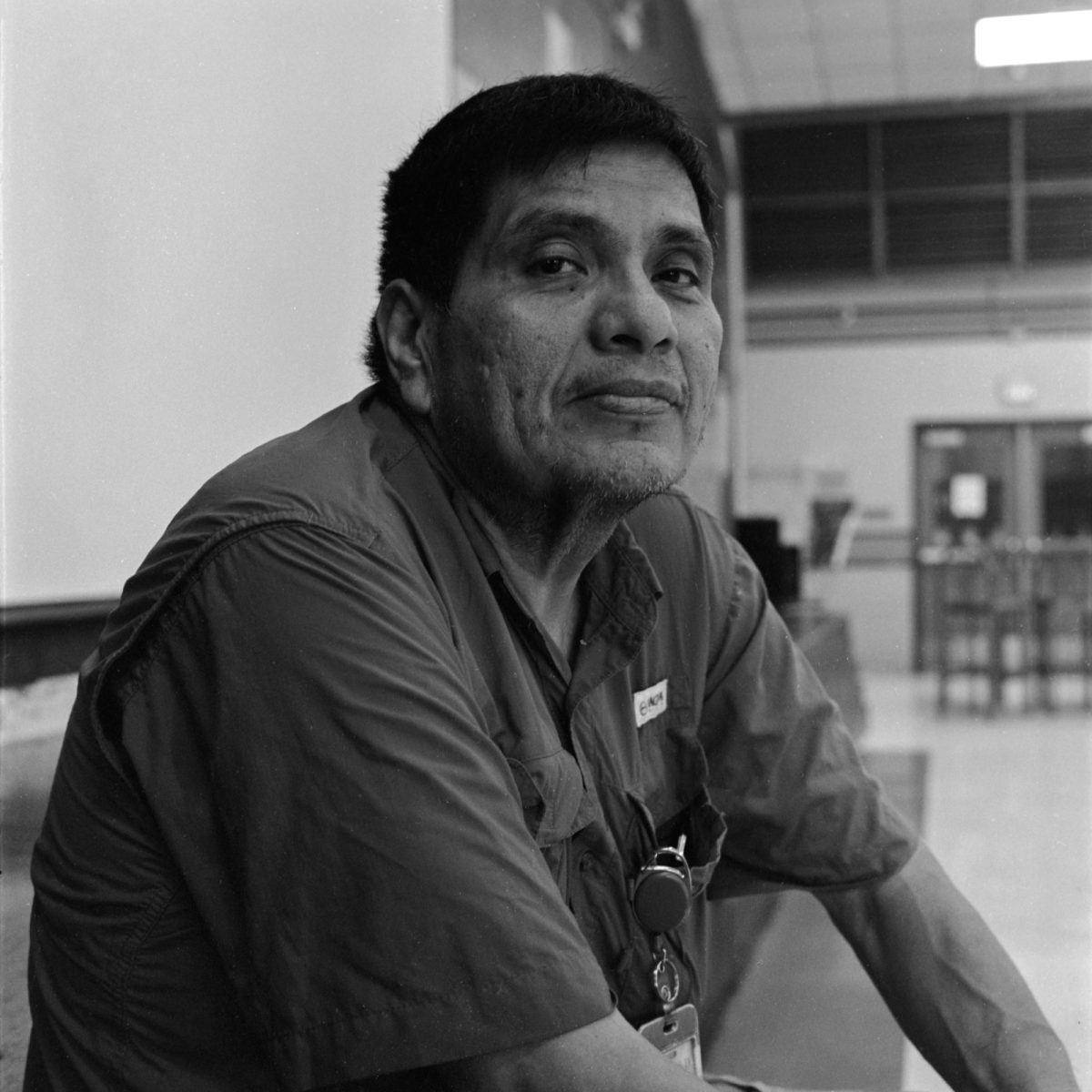

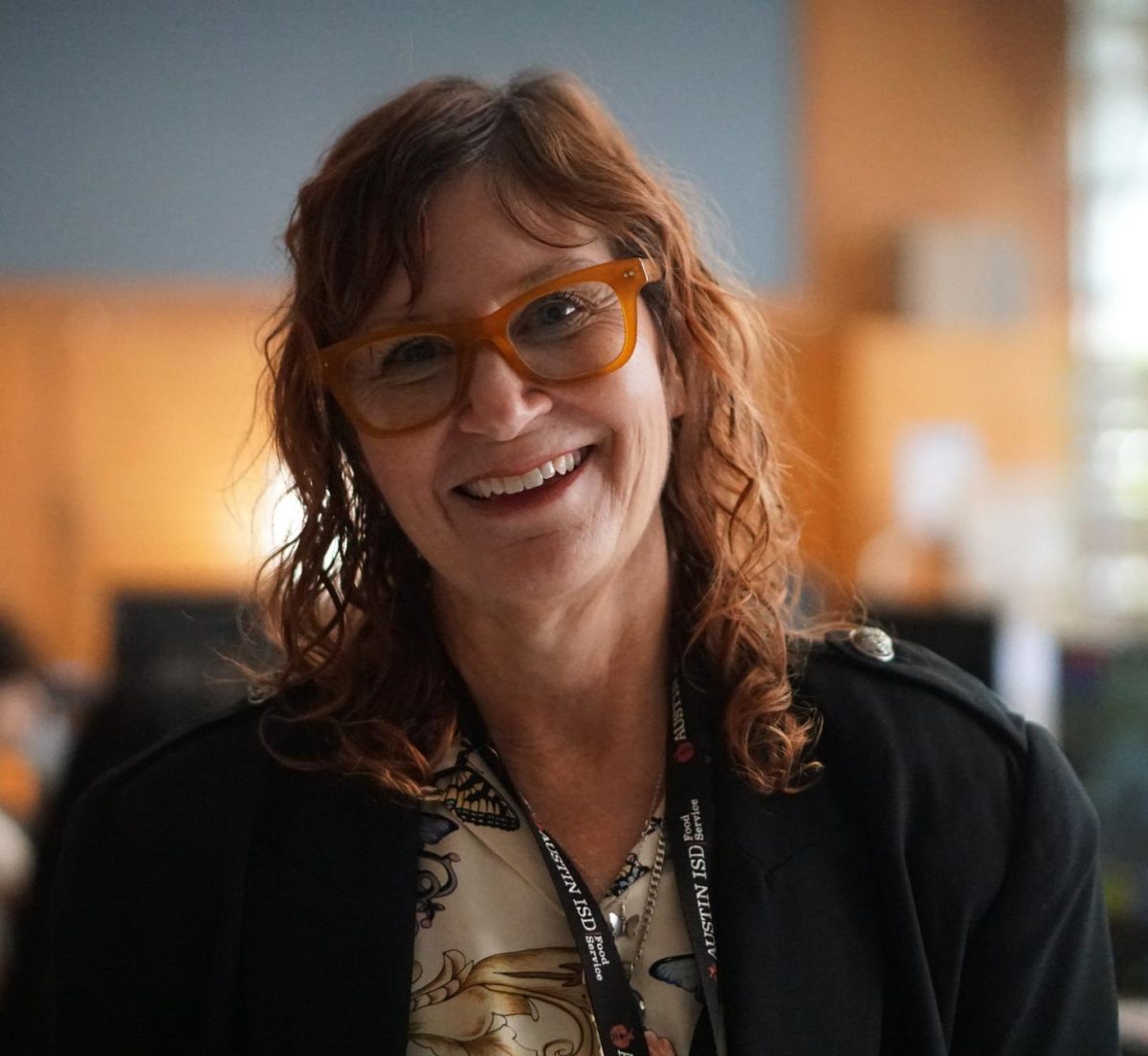

The Shield first met Joshua Eyler, the director of the Center for Excellence at the University of Mississippi, at SXSW EDU last spring, where he delivered the short version of his missive against traditional grades, a thirty-minute lecture,”Scarlet Letters: Fixing the Problem of Grades.” The staff was so impressed with his presentation that Francie Wilhelm asked him for an interview to discuss his latest book, Failing our Future: How Grades are Harming Children and Young Adults, and What We Can Do About It, that was officially released today by the Johns Hopkins press. It is available at JHU Press online, on Amazon and anywhere books are sold.

The Shield: How did you become interested in education?

Josh Eyler: I went to Gettysburg College as a student. I studied English and secondary education there. I decided not to go immediately into secondary teaching, high school teaching and instead went to graduate school for English. [I] went from there and became a faculty member for English at Columbus State University. While I was there I got involved with a lot of teaching initiatives and teaching improvement programs at the institution and decided that I wanted to move my career in that direction so I moved to George Mason University where I was the associate director for the Center of Excellence for two years.

Teaching centers like that in higher ed[ucation] are designed to help faculty become better teachers, so we use evidence-based practices, or evidence-based workshops to help them develop better practices. Then [I moved on to] Rice University where I helped them start a new teacher center, and I was the founding director. And while I was there I taught graduate courses in teaching and learning. And I recently five years ago moved to University of Mississippi where I am not only the director of the teaching center but also faculty in the school of education and teacher education, so I work on part of my day with faculty at the college to be better teachers and the other part I teach future and current teachers about teaching practices. So I’m kind of embedded in all these conversations that way.

But I also write books about education. And the first one I wrote was on the science of learning, and I have a whole chapter on failure and why it’s so essential for the natural learning process. We try things out, we get feedback, we try it again, but the school isn’t really set up for that kind of thing. And while I was writing that I ran into a ton of research on the problems with grades. It was really interesting to me, but I had to put it on a shelf while I finished that project, but the next thing I turned to was more of that research on why grades are an issue and what people are doing to reconcile those problems.

TS: Could you describe some of those problems you found in your research?

JE: So there are a couple of major categories of problems that grades cause. The most accessible are the obstacles they set up to learning. Grades are true extrinsic motivators, which means all the emphasis is on the prize, the reward. When you have a system that prioritizes extrinsic motivators, it means that the signals that you send are that the learning doesn’t matter: it’s the grade at the end of the road that matters. That means that grades set students up to be strategic learners, to do what they have to do to get the grade not to develop understanding in a particular field.

Another problem is that research shows that grades do not measure what we’ve been told that they measure. They are not good measurements of learning. If you get an A in introductory biology, it does not mean that you get an A in any introductory biology class, that that would be the same content that you would learn and the same outcome. They don’t measure learning, they measure students’ progress on an instructor’s individual goal. And we’re using them for major decisions like ranking and getting into college, that’s a real problem. The third thing I think connected to learning is that they set up an environment where students are afraid to take intellectual risks, to be creative, to be curious, because it’s not rewarding. And that is the last thing that we want with education, is for students to not feel like they can do that. So, it inhibits the learning process itself.

Another thing is that grades really mirror and magnify inequities that are part of our educational system. Students who attend schools with fewer resources, that one day move into higher education, you see that reflected in their grades. It’s no indication of who they are and what their potential is; it’s totally a reflection of what their previous educational experiences have been.

Grades have been used as punishment, especially for marginalized students. Grades are used as surveillance. I don’t know if you have grade portals at your school but that is only and truly surveillance. Everyone is looking at what you’re doing all the time and that’s a pressure cooker that’s hard to succeed in.

And the third thing that I’ve really focused on, the research over the last 10 years to show that grades are really contributing to the mental health crisis among teens and young adults. We have really powerful studies now to show that the academic stress caused by grades is a major contributing factor to what is called a crisis among youth in their mental health. And there are lots of different ways that plays out, depression, anxiety, stuff like that.

The reality of how academics specifically grades is affecting students’ mental health and wellbeing is something that we need to take very seriously. That’s not just an academic debate about how much do grades do hinder learning, that’s actual affect on people’s lives and selves. So, we know that’s happening, [and] we don’t do anything to account for that, we don’t do anything to mitigate it, we’re complicit in the harm that’s happening. That’s the landscape.

View this post on Instagram

TS: What do you think teachers can do that can alleviate some of this burden?

JE: So there are actually some school systems out there who are changing and have changed. But what can individuals do? There are a range of what we call alternative grading practices that lots and lots of faculty are experimenting with. If you take something like standard space grading, which is very popular in high schools, those that are changing, individual faculty, instead of being graded on each test that you take, for example, teachers will take instead a standard that the course needs to achieve in terms of the content and the skills. And then your grade is based on how many of the standards you meet over the academic year, not what you get on individual tests. Let’s take biology for example and let’s say one of the standards is understanding the chemical process of photosynthesis. Not only would you not be judged on that by one test alone, but there might be multiple means for students to meet that standard. Homework, set of test questions, quizzes, things like that to release the pressure valve a little on major, high-stakes exams. That’s just one example of what people are trying but there’s lots of experimentation happening right now in classrooms.

TS: I didn’t know there were whole districts moving away from traditional grading models.

JE: The one I featured in my book is in a suburb in Chicago. It’s a whole school district from kindergarten to 12th grade. As I was finishing writing the book I saw that the whole city of Santa Fe, New Mexico, is changing all their districts, so it’s a movement. Every year I see it picking up more and more steam.

TS: Do you think there are times when the current grading system can be helpful?

JE: It’s not that you can’t get any information from the grade that you get. Let’s say you didn’t study very hard, you get a C on an exam. That is a reflection that you need to study more. But the thing about the connection here is that learning is a really complex process and it’s also a highly individualized process. A student who may get a C on a first test in a class, could potentially get an A in that class, except that with the way grades work, is that C carries a huge calculation for the overall final grade. The student who just may take a little bit longer to learn that particular concept or something is going on at the beginning of the term, the grade will never reflect what they could have done and what their potential is because that C has carried a lot of weight. I think that grades can send some information that students can use that can be valuable, but because learning is so complex and so individualized, they are not really good for marking how much a person learns and improves over the course of a semester.

TS: Would you say that the current grading system hurts both high and low achievers?

JE: I do think that. The harm is not uniform and it’s not the same for each of the groups. For students who are getting lower grades, the messages that those grades are sending are: you’re not cut out for this or no matter how hard you work, you’re never going to get there. It doesn’t allow room for them to grow because they’re behind immediately, and it’s always about catching up and not about learning. And they’re doing that in the face of messages that the grades are sending. No matter how supportive the teacher is, the grading system pushes back in the opposite direction. For the high achievers, grades really set students on a race that can never be won. Oh I got an A, I need to get the next A. It’s just ramping it up, the competition and the pressure. It’s still not putting the focus on learning and understanding, it’s making everything this intense competition and pressure filled arenas.

No one’s talking about what does John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath mean; everyone’s talking about “I have to get the 99.”

That’s the strategic learning I was talking about and it’s a big part of the equation that leads to the impact on mental health, it’s not a healthy environment for anyone to be [in].

TS: What do you have to say to students who are struggling or feel trapped by grades?

JE: You all spend most of your time in schools and most of your lives at this point in your life have been in a school setting. But I do have a chapter about how parents can help their students acclimate and adjust in this kind of environment. First and most importantly, it’s easier said than done, understand that your grades are not a reflection of you as a person. The grades represent a system that is inequitable and is not really keyed towards learning. If you understand that it’s easier to separate yourself from the grades.

Some of the other things I talk about are really parents helping their children cultivate interests outside of school. If you happen to be really interested in anime or movies from the 40s, that’s really cool and people should develop those interests. As you develop those interests, it helps you to understand that learning for its own sake is actually something that will enhance your life and help you become a lifelong learner.

The focus is not on learning, but on the competition. Cultivating interests, cultivating curiosity, helping to see that curiosity is something that can carry us through our lives is something of value in and of itself. Developing tools to be resilient when you get a negative grade, that it’s not the end of the world. You can use that as a stepping stone to study harder, working through the veneer of grades and developing strategies to combat the message that they send.

View this post on Instagram

TS: Do you see alternative grading styles as a solution?

JE: Yes because I don’t see in the immediate future I don’t see a lot of places getting rid of grades. If our reality is working and studying in systems that give grades, then we have to use strategies that can mitigate the damage. So I do alternative grading models and the school districts changing entirely as a way to work within a system that gives grades but to minimize the damage as much as possible.

TS: Is there anything else you would like to add?

JE: These are sometimes really hard conversations to have about grades because nothing is more fundamentally baked into education, the foundation of education than the idea of evaluation and grades. So, people take this as a given that of course you could give grades in school, what else would you do? There are serious conversations about grades that you can have with respect to grades and it begins with believing that change is possible in the first place. Helping folks to see it hasn’t always been this way, it doesn’t have to be this way. Change is possible and the work really begins with individual groups and teachers.

Eyler has been involved in secondary and higher education for several years now, previously working on initiatives at Columbus State University, George Mason University, and Rice University, and has spoken at several universities and conferences speaking on the harming effects of grades in the current school system and presenting alternate methods to implement more beneficial learning. Eyler has published several books discussing his theories, including, How Humans Learn: The Science and Stories Behind Effective College Teaching.