The class of 2024, is the first class of students to apply to colleges and universities without federally protected affirmative action in 57 years. As a result, students from historically underrepresented groups have been figuring out how to adjust to the absence of affirmative action as a criterion in the college application process.

Instituted by executive order in 1967, affirmative action refers to the active effort by government, business and educational institutions to improve employment or educational opportunities for members of minority groups and for women in order to remedy to the effects of long-standing discrimination against such groups. The Supreme Court effectively ended affirmative action in June of 2023, when it ruled in a 6-3 decision that race-based admissions criteria at Harvard and the University of North Carolina to be unconstitutional.

Senior Sivaan Sharma is one of the first of his class to apply to colleges without the safety net of affirmative action supporting his application. Encouraged by a friend to write an article detailing his personal experiences, Sharma wrote an account of his encounter with affirmative action that was published on the CNN website. Entering the college application process with an understanding that affirmative action was no longer a factor in admissions, Sharma decided to write about race in his essay so it would be considered.

His decision made sense given the majority option written last June by Chief Justice John Roberts. While Roberts argued in the decision that affirmation action programs violate the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, he also maintained that “nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicants discussion of how race affected his or her life.”

For a university to consider the impact or racial identity or discrimination, the applicant first has to write about it, and so Sharma did.

For Sharma, an Indo-Fijian student, opportunities were hard to come by growing up, and he struggled with discrimination because of his identity. To make the decision to write about race in his essay, however, Sharma had to forgo his original idea for his common app essay, and completely change it to write about his battles within his identity.

“It’s created a dilemma between you know, which essays do I use?” Sharma said. “Which ones do I sacrifice? What I’m passionate about, what I can write about or do I talk about my race, something that I’m now forced to do?”

Like many students across the country, Sharma and his family cannot independently afford the rising costs of college tuition and therefore hope to rely on strong applications to get into colleges and to secure financial resources to pay for it.

“We didn’t have a lot of money to send me off to college,” Sharma said. “And so I wanted to make sure that my application was ready, so I did it very early on. I had a lot of ideas. I knew exactly what I wanted to do.”

Before the summer of 2023, Sharma devised a plan for his college essays, but that plan had to be changed after he learned of the affirmative action ban over the summer.

“And then whenever this happened, it was suddenly like a wake-up call for me like, ‘Whoa, some of these colleges are not even going to look at my application unless they realize some of the shortcomings can’t just be explained by a box anymore,’” he said. “The only way to have that recognized now is if you write it in your essay, and there are a lot of very different nuances that used to be encapsulated by a box that we now have to write about [explicitly].”

Many students in the past relied on affirmative action to have their race and ethnicity taken into account and to improve their admissions chances at prestigious colleges and universities.

“Some people just lost a lot of hope or security that you know, maybe they’d be considered for some of their top schools, and some people have stopped applying to the reaches,” Sharma said. “Like I had a friend who wanted to apply to Harvard and at this point, he just was like, ‘Nope, I can’t even do it.’”

A poll of 1,680 American adults by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that 63% believe that the Supreme Court should not prevent colleges and universities from considering race during the application process. On the other hand, 62% believe that grades are extremely important during the admissions process, and 47% believe that standardized testing is.

In 1978, grad student Allan Bakke, had applied to the medical school at the University of California at Davis, and got rejected, despite his qualified application and his above-average stats. The university allowed white applicants to apply for 84 out of 100 spots, and the leftover 16 were reserved for minority students. Bakke sued the school, arguing that the racial quota was unconstitutional and violated the Civil Rights Act. In the case Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr. cast the vote that ordered the medical school to admit Bakke.

At the time, Bakke successful challenged the school’s use of affirmative action, but the decision was controversial and divisive. A then record number of 58 amicus briefs were filed, showing the wide range of opinion on the issue of affirmative actions. Even the court was divided. Six different Justices wrote opinions on the case. Affirmative action has remained controversial, but many people support it because it provides schools a way to diversify their student body. In a statement released shortly after the repeal of this act, UT Austin released a statement saying that it would “make the necessary adjustments to comply with the most recent changes to the law and remain committed to offering an exceptional education to students from all backgrounds.”

NEW: @UTAustin’s statement on the SCOTUS ruling on the use of race in college admissions:

“UT will make the necessary adjustments to comply with the most recent changes to the law and remains committed to offering an exceptional education to students from all backgrounds” pic.twitter.com/tbp3e7GUk5

— Megan Menchaca (@meganmmenchaca) June 29, 2023

The University of Texas has its own role in the history of race-based admissions in American history. In 1946, Heman Marion Sweatt, a Black man, applied for admission to the UT Law School, which was at the time was all-white. Sweatt met all the application criteria save for one: his race. The Texas Constitution at the time required separate schools shall be provided for Black children, but at the time of Sweatt’s application there was no separate law school, so the Texas established a temporary one, which prompted the state court to dismiss Sweatt’s case. Upon appeal, the Supreme Court ruled that states that did not have separate public graduate and professional schools must admit Black students to only existing, all-white school because the equal protection clause required it. So in the fall of 1950, Sweatt and several other Black students enrolled at UT.

But as any knowledgeable observer will tell you, the court has undergone significant personnel changes from 1950 to 2023. Social studies and government teacher, Erin Summerville, said she believes the overturning of affirmative action came precisely because of the changes at the Supreme Court.

“I believe there was an ideological shift on the court, and the new appointees,” she said. “But the arguments made by the justices, they were asking reasonable questions about how long or how long into the future, should colleges [be] using race as a factor and also wondering if, by not using other metrics, they’re leaving out important criteria.”

Summerville, very versed on the governmental side of affirmative action, said it had its roots in the 1970s.

“Earlier in history, the thought with affirmative action was about promoting equality but also helping historically disadvantaged people get into college,” she said. “Starting in the 90s, the way of thinking is a little bit different. It’s more about diversity on your campus. And so, in the most recent ruling, they had to unpack: is the point of using race to, you know, help those who have been historically disadvantaged or is it to enhance diversity on campus?”

Many universities and colleges currently have promotional slogans and messages on their campuses about fostering diversity, and creating a community of some sort. They focus on including diversity in these campaigns to show students that they are committed to admitting people of all backgrounds.

“So I think, you know, we have to first settle on what is the goal of using race?” Summerville said. “And I think these days a lot of folks who want race to be used talk about it for promoting diversity.”

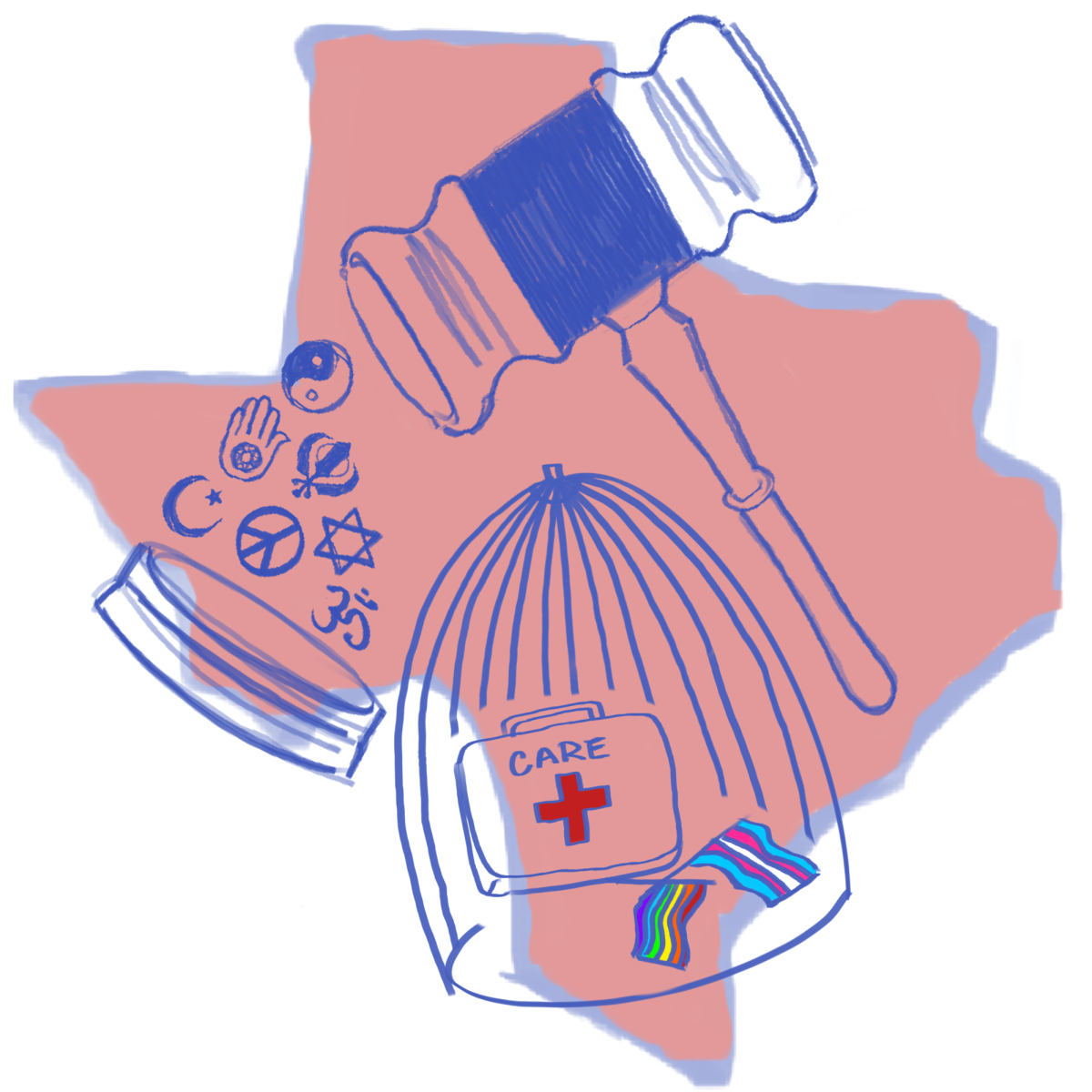

It’s not just affirmative action that is making it more difficulty for Texas universities to promote diversity either. Senate Bill 17, a state law signed into law by Gov. Greg Abbott on June 17, 2023 and made effective Jan. 1, bans diversity, equity and inclusion offices, programs and training in Texas public universities. In response to the law, UT-Austin has closed its multicultural center, ended a scholarship program for undocumented students, canceled a lecture on finding LGBTQ mentors in higher education.

How Texas universities can balance the desire to promote diversity and comply with Senate Bill 17 remains to be seen, but for class 0f 2024 seniors just getting admitted to state colleges and universities remains the primary matter of the moment.

Senior Gigi Kahlor had a similar experience to Sharma, when she was applying for colleges this past fall. A big UT fan, Kahlor was hoping to get into UT and was leaning on affirmative action to help her. When hearing about the ban late last summer, Kahlor was very surprised.

“It kind of sent me into a spiral of like ‘Oh, this could mean that I don’t get into some of the colleges I wanted to go to,’’ Kahlor said.

Kahlor had been hoping that affirmative action might improve their admission chances and also potentially lead to scholarships and financial aid.

“I was kind of hoping that affirmative action would help me get scholarships and help me get into colleges that are harder to get into when you’re a minority,” they said. “And if you were first generation, but adopted, that still doesn’t count as first generation.”

When asked if the repeal of affirmative action made them write about race in their essay, Kahlor said it did.

“I have to because it’s a big part of my story,” they said. “Not just because I’m this race, but because it’s part of who I am.”

Riley • Apr 2, 2024 at 2:42 pm

I really liked the way that the reporter went into detail about how this affected minority students admission processes. It seemed like it was very well reported before writing. I wish that they explained what affirmative action means exactly at the beginning because not everyone is as familiar with that as seniors applying to colleges.