“Electronic mail transmissions and other use of the electronic communications shall not be considered confidential and may be monitored at any time by designated staff to ensure appropriate use for educational or administrative purposes.”

The following quotation is a part of the AISD Acceptable Use Guidelines, a set of conditions that students must accept before logging on to their school-issued Chromebooks. By accepting these guidelines, students are consenting to having their work monitored, filtered and read. While local and district officials have long monitored student expression on school-issued computers and accounts, it has recently contracted with a new monitoring service, Gaggle.

Gaggle: A system designed to protect

Principal Nicole Griffith describes Gaggle as a third-party software program that actively scans documents for keywords that signify a threat. Once a keyword is flagged, it may be read by McCallum or AISD staff to determine whether the threat is credible.

“If someone is plotting something nefarious towards our campus, we all want to know about that,” Griffith explained. “We all want to stop that before it happens. Gaggle is a tool at our disposal to help us do that job… to help keep people safe.”

At McCallum, assistant principal Andy Baxa primarily oversees Gaggle, although other faculty members may step in depending on the issue. According to Baxa, programs that monitor and filter keywords have been in place for years; however, he describes Gaggle, which has been in place for at least two years, as more extensive. While it is known that Gaggle works 24/7 on Chromebooks, neither Griffith nor Baxa know whether Gaggle extends to personal computers.

Flagged information ranges from campus threats to drug use to explicit language and self-harm. Upon receiving a flag, Baxa is primarily responsible for categorizing the information by threat-level and threat-type, then determining how to proceed. Most of the time, Baxa said, flagged information doesn’t lead to any direct action. Certain English assignments, such as senior college essays, produce large amounts of flagged content but rarely result in any intervention.

“Oftentimes college essays ask you to write about a challenging time in your life,” Baxa said. “Maybe if they’ve had suicidal ideation, and they’ve been able to get past that, kids will write about that, so we get a flag because they’re writing about suicide. But we can clearly see that this is a college essay. On those we can confirm as a school assignment, there’s no threat associated with it. Ninety percent of those are closed out, and we don’t even talk to the student about it.”

In cases such as drug use, Baxa’s top priority is discerning whether the flagged behavior presents a potential threat to the students themselves.

“I try to determine: is this a credible threat or is it not? Is this dealing with drugs or self-harm? Could you do damage to yourself?” Baxa said. “More often than not, we’ll have a conversation with the student and then we’ll have a conversation with the family. We’re trying to get the student the support they need if they do have a problem.”

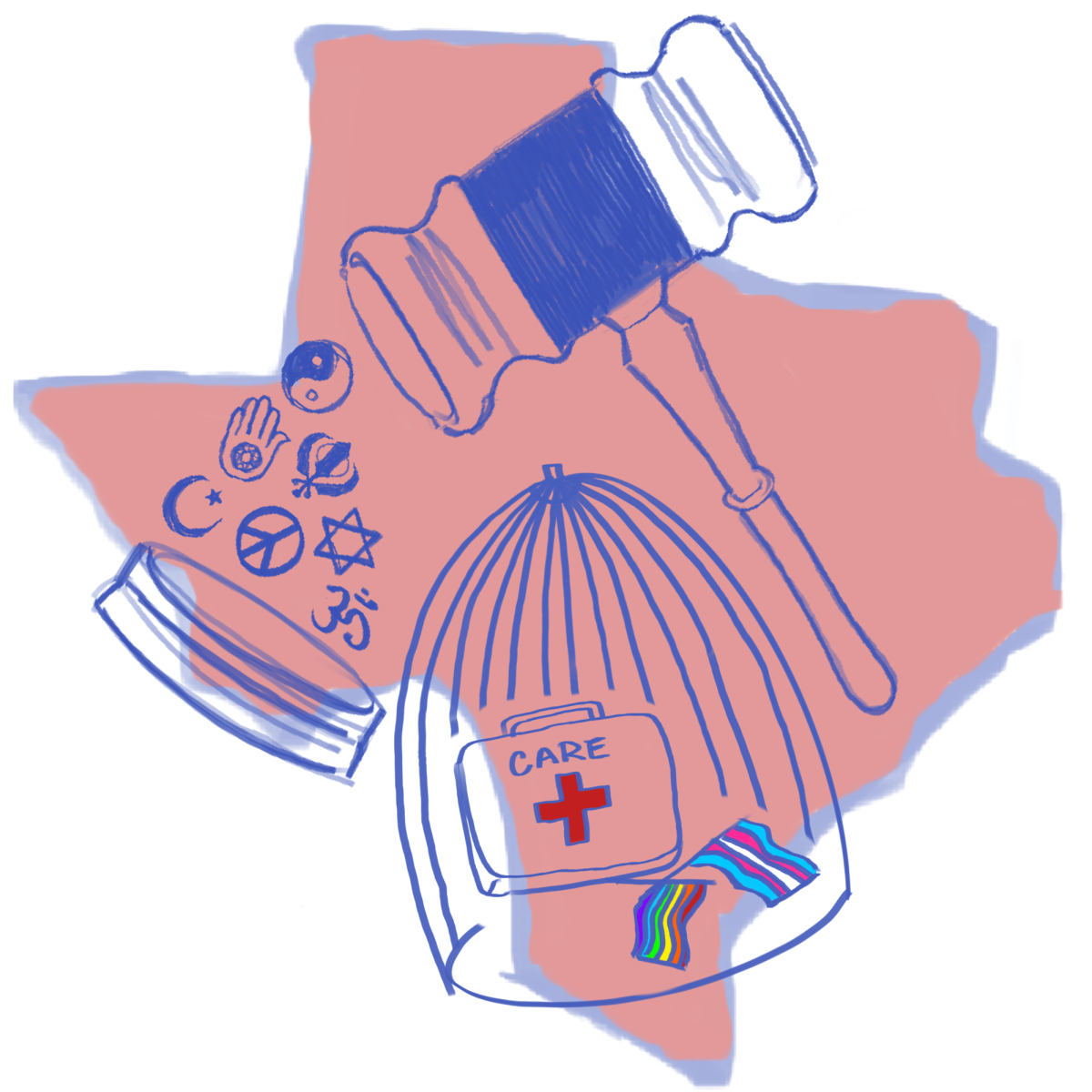

Griffith emphasizes that the school’s involvement with drugs and substance-related issues is ultimately designed to help students. When faced with an indication of drug use, abuse or drug distribution, Griffith explains that educators are legally obligated to report the issue.

“We’re not doing that with the angle of ‘Oh, let’s get all these children in trouble,’” Griffith said. “That’s not the purpose of it. We’re looking at it from strictly a safety consideration. There is abuse that may need to be flagged. And it’s our obligation to report abuse. That’s another part of the job that’s so important. All educators by law have to report drug abuse when it comes our way.”

Even though minor drug use is considered a felony, Baxa claims that police will not get involved since there is no observable action.

“Police actually have to see you do it,” Baxa said. “You can sit there and write ‘I smoke marijuana 24 times a day.’ You can say it all you want, but just because you say it doesn’t mean the police can do anything about it.”

Gaggle can also be used to obtain information related to possible parental or sexual abuse. Upon receiving a flag related to possible parental or sexual abuse, it falls on Baxa, the administration and counselors to determine whether a report must be made to Child Protective Services.

The Texas Department of Family and Protective Services website states that “Texas law requires that any person suspecting that a child has been abused or neglected must immediately make a report.” DFPS also emphasizes the importance of making a report within 48 hours of any initial suspicion. According to Griffith, teachers that don’t follow these guidelines risk having their teaching license revoked.

When Gaggle flags something related to possible parental or sexual abuse, Griffith explains that counselors typically talk to the student in question before a report is made; however, even if a student doesn’t want a report to be filed, if a counselor suspects neglect or abuse, the counselor is still obligated to submit the report. This includes past abuses and assaults.

“We don’t use black-and-white judgment on any of this,” Griffith explained. “It’s all very complex. We really, really want to be respectful of students.”

Students and teachers speak out

While Gaggle is not considered confidential, up until recently, not all teachers knew about it. This year, Griffith decided to tell teachers about Gaggle because she believed students deserved to know what was happening.

English teacher Daniel Myers was one of the teachers who only heard about Gaggle this year. Upon learning about it, he felt he had broken an unspoken promise to his students.

“I feel as though we have an agreement,” Myers said. “There’s a certain understanding that what I need to report is always ‘I’m gonna hurt myself, I’m gonna hurt someone else, I think someone else is going to hurt me.’ In my room, beyond those things, what you write is between you and me. There’s a trust that we build. And that’s very important to me—that that trust is there—because without it, I don’t feel like I can do the thing I’m best at, which is the relationship part of teaching.”

After finding out, Myers immediately communicated his knowledge about Gaggle with his students.

“We’re not here to lie to kids,” Myers said. “We’re teachers, we’re supposed to tell them the truth. Kids deserve to know who’s reading their work.”

Evie Cox, a student in Myers’ third period English class, found out about Gaggle through Myers. Believing that Gaggle was an invasion of students’ privacy, Cox decided to take action against AISD and start an online petition against Gaggle.

“I was disgusted,” Cox said. “I’ve never done anything against AISD in my life. But it went too far, and at that point, I was like ‘OK, now it’s my personal life you’re getting into.’”

Cox’s petition, addressed to Austin ISD, has garnered over 270 signatures as of Nov. 8. Part of Cox’s grievance with Gaggle is that she believes the money spent on the programming would be better spent on other mental health programs for students.

“We should put that funding … towards more psychiatrists, more counselors who specialize in mental health, and then maybe more students will come talk about it [their mental health],” Cox said.

Balancing privacy and safety

In the days after learning about Gaggle, Myers decided to offer notebooks to his students so that Gaggle could no longer flag their writings. He explains that in both his Excalibur and English classes, he encourages his students to use writing as a tool for healing.

“I believe in weaving straw into gold,” Myers said. “Arts is alchemy and we can take pain and suffering and weave it into beautiful things.”

Myers believes Gaggle strips students of their artistic autonomy. He likens the situation to when Edward Snowden leaked a plethora of documents about government surveillance.

“[Snowden] talks a lot about how all these documents are collective, all this surveillance, but they don’t use hardly any of it,” Myers said. “He compares it to pointing a gun at someone but saying ‘Don’t worry, I’m not gonna pull the trigger.’ But it’s like ‘you’re still pointing a gun at me.’”

Baxa is aware of the balance between privacy and safety, and understands that oftentimes, one must be sacrificed for the other.

“But if I can stop one school shooting by this invasion, then to me, it’s worth it,” Baxa said. “If I can get that one kid who’s on the edge the help they need, then it’s worth me reading through nine others who didn’t need the help. Even if it’s one life saved, then to me, it’s worth it.”