It’s time to write off annotation.

Annotation should help us enjoy books; instead, it takes fun out of reading

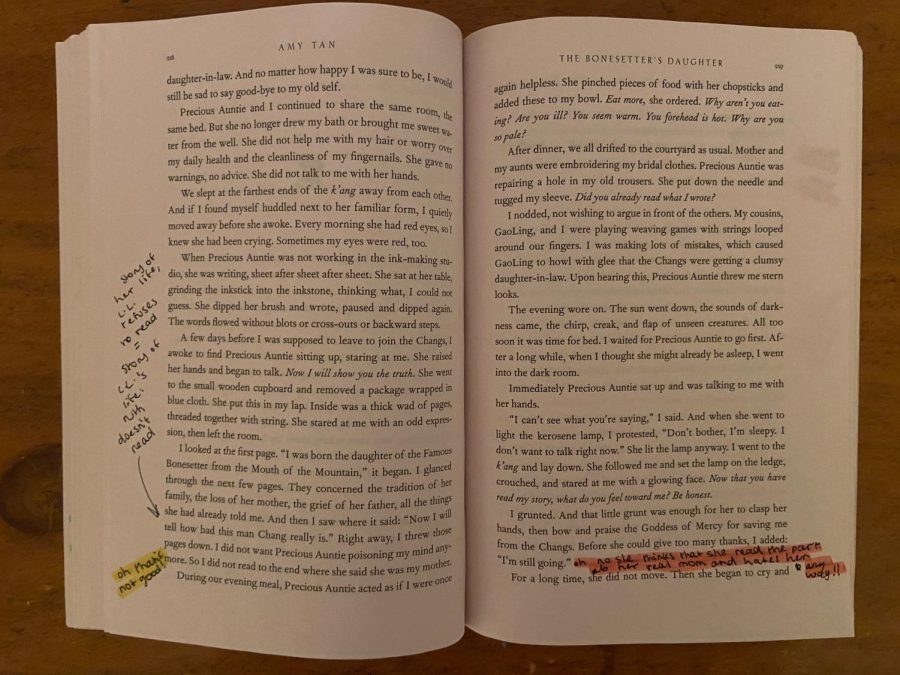

For my summer reading assignment this year, I read the The Bonesetter’s Daughter by Amy Tan. We had no additional assignments with the reading, except for annotating the text.

There is one thing about me that everyone knows, and if they don’t, it doesn’t take long to figure out.

I love reading.

As soon as I learned to read, I was never caught anywhere without a book. In fact, I used to read so many books at once that I made a schedule to determine how much time to spend on each one. One of the walls in my room has bookshelf-patterned wallpaper. And recently, my bookshelf collapsed due to the sheer amount of books crammed on it (rest in peace, Billy).

Loving books is my primary personality trait. And yet, when the time comes in English class to crack open a book and get to work, I’m filled with dread because I know I’ll have to annotate it.

Every student has had to, or will have to, read and annotate a book for school. It’s seen as a way to help us glean deeper meaning from the text and better remember the themes and motifs of the book. By all accounts, annotating is a tried-and-true strategy; however, I don’t think it’s actually very beneficial to learning.

I find annotation tedious and frustrating. First of all, teachers often require annotations but do not actually check the content of them. This creates the problem of annotations just being completion grades, rather than a tool to help us process the material. I can’t count the number of times I’ve made something up to write down just to hit my “quota.” I earn the grade, but it doesn’t help me understand the book better.

My past teachers have also been too vague when telling us what we should annotate. Instead of directing us to look for imagery, similes, etc., the only instruction is: annotate the chapter. This is far too general. If I am meant to do a deep dive into the text, I need to know exactly what I am supposed to be looking for.

What’s worse, annotation distracts me from the actual text. When I read a book for school, instead of reading, I am looking for things to annotate. I’m so focused on getting enough annotations that a book I might otherwise enjoy is reduced to a mere task on a to-do list. This is the danger of the way we’ve been taught to annotate: it contributes to students’ hatred of reading.

We learn better when we’re excited about and interested in the topic. If someone does not enjoy reading, they are not as engaged with the text because they don’t care about it on a personal level. People who don’t care about what they’re reading about won’t have meaningful takeaways from the text. They certainly won’t put their hearts into annotating it, which, in theory, is the whole point of annotation.

Reading is instrumental because it provides a window into unfamiliar cultures and perspectives. If we read books by and about people different from ourselves, we find out more about the world beyond the small bubble of our lives. And, according to the Harvard Business Review, reading literary fiction improves one’s empathy, theory of mind and critical-thinking skills. Even with these benefits in mind, however, several people I know have learned to hate books because of the way we read them in school. A big part of that is annotating.

I want to make it clear: I’m not completely against annotation. It’s proven to help increase students’ reading comprehension. In fact, when I read for fun, I often highlight my favorite lines and write my thoughts down in the margins. But the vague way we’ve been taught to annotate is detrimental to our learning.

There are ways to change that. Instead of telling students to write something down every chapter, teachers should give them specific instructions regarding what to look for. For example, devote one chapter to looking for imagery and another to looking for certain motifs. Teachers also should encourage annotation but not grade it. Students will be more excited to read the assigned work and less likely to just read its SparkNotes.

It makes my book-loving self sad to see so many of my fellow students be turned off of reading because of academic annotation. But hopefully, better annotating strategies will be more widely taught in the future. And, in a perfect world, student bookshelves will be collapsing all over the place.

Your donation will support the student journalists of McCallum High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Nienke van BookSomeTea • Apr 29, 2025 at 11:10 am

From one booklover to another: I totally get it. In my country (I live in The Netherlands) we do not annotate (books are way to expensive to do that), but we do have something similar that kicks all the fun out of reading.

Greetings and a stroopwafel for all of you,

Nienke