On April 6, McCallum principal Nicole Griffith sent an email entitled “Back to Mac” encouraging parents to send their students back to campus for the final six weeks of the school year. After a year of complete flexibility in choosing in-person versus remote attendance, many families were surprised by this new messaging. Griffith explained that this change in tone came from staff consensus that new safety measures, including widespread vaccinations among teachers and staff, made it possible for the learning model to shift towards in-person instruction.

“The ‘Back to Mac’ [email] came from the fact that our teachers were feeling a lot more comfortable being here with students,” Griffith said. “They were given the opportunity to get vaccinated, our most vulnerable teachers had been vaccinated for months. … We feel very confident in having kids back. We know how important it is. We also kind of felt… that students who are able to come back, especially our ninth-graders who have never been on our campus, to come back for this last part will help them feel more confident in starting next year.”

Before the “Back to Mac” email was sent, teachers were notified at a staff meeting about a “change in tone” coming from the school regarding in-person learning. According to English teacher Nikki Northcutt, however, the McCallum teachers didn’t actually receive the email once it was sent.

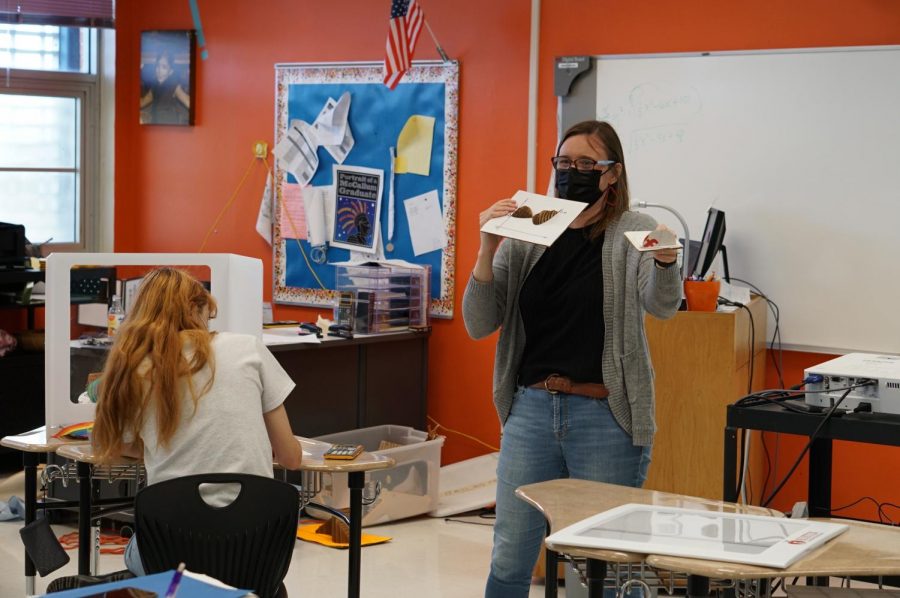

Upon hearing about the email from a Facebook tip, Northcutt felt the need to re-arrange her classroom.

“From the beginning of the year, I have been saying I will not go over nine desks,” Northcutt said. “I’m not doing it because that’s six feet and I want to follow guidelines and then I added three desks. So now I have 12. I bought a tape measure and angrily measured between desks … and it’s still five and a half feet.”

Despite the added desks, however, Northcutt’s largest class is still only seven in-person students. According to Northcutt, this group of seven students “fell in love with each other over Zoom,” which inspired the seven to come back to in-person classes. The slight shift in the amount of in-person students has forced Northcutt to alter her teaching model; however, this shift hasn’t affected Northcutt as much as she originally thought it would.

“I am getting a lot less done because when I go to grade during the asynchronous portion, all my students want to talk to me,” Northcutt said. ”I love talking to them, but then I don’t get any work done, which, to be fair, is how it normally is.”

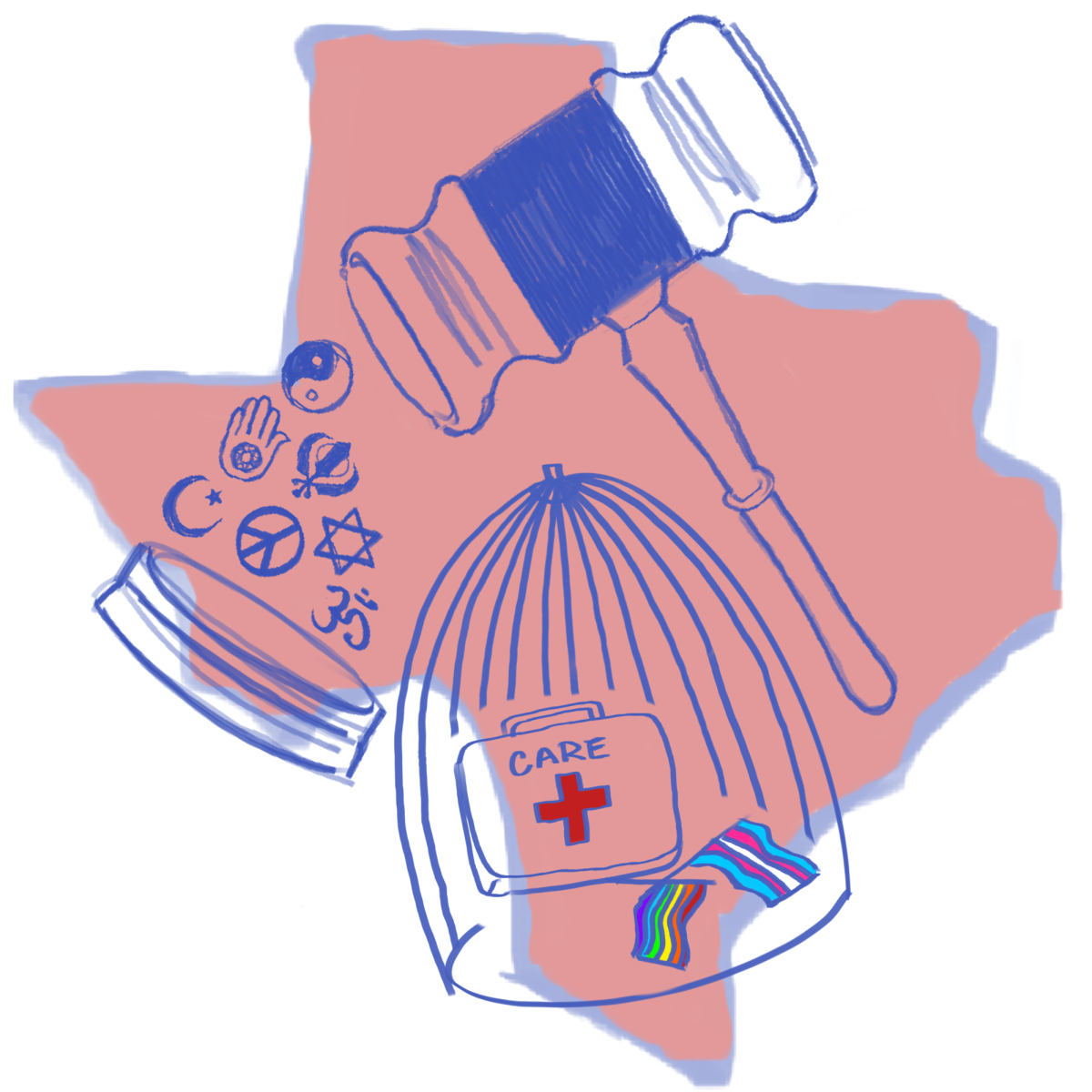

Soon after this push on the campus level to encourage students to return in person, the message began to echo district-wide. On April 13, AISD principals all across the district sent out identical emails encouraging students to return in person and claiming that it was safe to do so. Griffith now explains that this messaging was in part coming from a need for funding from the Texas Education Agency.

In March, the TEA announced that school districts would be “held harmless” in terms of funding for drops in attendance rates due to the pandemic, but not without a few stipulations. Griffith explained that the release of funding to the school districts depends on attendance levels during the sixth (and final) six weeks of the school year. The requirements are as follows: Districts can either meet an average on-campus attendance rate equal to or greater than 80 percent of the total students educated, or districts can meet an average on-campus attendance rate equal to or greater than an on-campus snapshot of attendance for one day in October.

For AISD, the on-campus snapshot from October is equivalent to about 23.6 percent attendance, and meeting this average for the sixth six weeks will secure the funding for the fourth through sixth six weeks. Each six-week period is tied to about $4-5 million in funding. The funding for the first and second six weeks is already secured, meaning AISD has obtained about $10 million out of the hopeful $30 million budget for the year. According to Griffith, in April, total in-person attendance rates in the district were just over 35 percent. This means that it’s very likely that $15 million more in funding will be secured for the second semester.

The only thing left up in the air is about $4-5 million in funding from the third six weeks, which AISD previously lost due to the decision to keep students completely online for the week following Thanksgiving break. However, the TEA has said that this funding can be earned back if the sixth six weeks attendance is 20 percent greater than the on-campus snapshot in October. This amounts to a target of about 44 percent districtwide on-campus attendance if AISD is hoping to secure this funding.

Griffith explained that this presents a dilemma for the district between pushing for the funding and emphasizing the health and safety of the AISD community.

“We have to have our attendance at 44 percent, so there is a concern from the district standpoint,” Griffith said. “And this is a hard topic, I think, for districts across the state because we don’t want to lose funding, right? We also don’t want families to feel like, ‘Wait, do you care more about money than my kid?’ Well, no, I mean, the money goes to your kid. So if we lose that money, it directly impacts children. But we also want people to make a decision that’s safe for themselves and for their family.”

Spanish teacher Juana Gun wonders why educational funding is being withheld from schools in the first place.

“It’s one of these things where, ‘Stay away because it’s dangerous. Come back because we need the money.’ So there’s something wrong with that,” Gun said. “The money’s there… If you’re not going to give the money to the schools, who are you giving it to?”

There is a catch to this attendance-based funding system: students’ attendance only counts toward the funding if they attend their second or sixth period for 13 days. This means that students who choose to go for half-days in the afternoons or just a few classes occasionally will not be counted in the race for funding.

Is it possible to gain this extra $4-5 million? Griffith thinks that at McCallum it’s pretty much impossible, but she has hope for districtwide numbers to go up.

“I would love that at McCallum, I would love for us to get closer to 50 percent,” Griffith said. “I mean, I think it’s doable, but I’m not going to hold my breath. I want kids to come back; we would be happy to have that many kids back, but, across the district, elementaries are seeing much higher attendance than high schools.”

Griffith explained that in April, districtwide attendance rates were about 35 percent. However, if the McCallum attendance trends are any indicator, she thinks it’s possible that AISD may yet reach the 44 percent needed to secure $5 million in funding. On Tuesday May 11, in-person attendance at McCallum surpassed, 400 students, whereas just over a month before, that number was only 189 students.

Senior Emily Arndt is one of the 227 students who returned to McCallum on April 12 following Griffith’s email. Being fully vaccinated, Arndt explained that she finally felt comfortable coming back to campus.

“Both of my parents are high-risk and it’s been very important for me to not get involved with risky behavior,” Arndt said. “My entire family is fully vaccinated now, so I felt much more comfortable returning.”

Like many other students, Arndt has found online school to be very difficult. The desire to improve her learning situation, alongside wanting to see some of her classmates in person, contributed to Ardnt’s decision.

“I struggle with learning blocks,” Arndt said. “This late in the year, it has become very hard to focus. I knew that coming back would allow me more time to work with my teachers and less distractions. I’m also a very chatty girl, and I was looking forward to being able to see my classmates beyond the black screens.”

Griffith’s email, however, also spurred some criticism. Upon seeing Griffith’s email, senior Ari Miller-Fortman immediately thought the push to come back had something to do with the Texas Education Agency and voiced her opinions in the comment section of a MacJournalism Instagram post covering the email.

“I spoke out about the decision and ‘push’ to come back to campus because I truly believe that TEA is behind it,” Miller-Fortman said. “Instead of accommodating for the lack of attendance due to COVID, they are continuing to partially base their monetary system on student attendance. That just isn’t realistic, and it ended up making students, including myself, feel pressured.”

This perceived lack of transparency has ultimately halted Miller-Fortman from returning to campus.

“If I were to come back to school, I’d want to know the real reason why my attendance matters,” Miller-Fortman said. “Sometimes it can be hard for students not to feel like we are just factors of money for TEA and AISD. I know this is not the case, but personally, I want full transparency from our leaders about why our attendance is a big deal rather than playing a cover-up for TEA’s absurd decisions.”

Ardnt disagrees, however, believing that the recent push to come back has more to do with teachers wanting to see their students than obtaining funding from TEA.

“Even if there is a push for funding, the teachers do genuinely want students back, and it makes the campus life better,” Arndt said.

As students make decisions about their learning model that may differ from their peers, Griffith hopes that students and their families can practice acceptance.

“There’s no winning, and the reason there’s no winning is because everyone’s making the decision that’s right for them,” Griffith said. “What I do hope that we do as a community is that we lift each other up, and we respect each other’s decisions.”

Griffith explained that the intent behind the email was indeed to improve the quality of on-campus life and learning as well as social and emotional health.

“We sent out the ‘Back to Mac’ email, which I 100 percent knew was going to be controversial, and it was,” Griffith said. “[But] our students’ emotional and social safety is also in consideration, and that’s the truth. There’s a physical safety to this that people are worried about with COVID. And that’s totally fine for people to stay at home. But there’s also social and emotional safety. And a lot of our students really need to come back, probably a lot who are still at home.”

Freshman Luke Wheeler started going to school in person after Griffith’s “Back to Mac” email and said that it almost immediately improved his experience.

“For anybody who can, I would suggest coming back because… the school experience got way better for me when I started going back, and I feel like that would happen to a lot of other freshmen if they came back,” Wheeler said. “Obviously, it’s not doable for everybody, but it’s just a better experience.”

As the push for increased attendance leads to classrooms looking a little fuller, the instructional model has shifted as well for many teachers.

Gun loves that she gets to spend more time chatting with her students, as opposed to how lonely she felt in an empty school at the beginning of the year.

“The happy changes are that I’m seeing more of my students, and it makes the day a lot less lonely the more people I have around me,” Gun said. “Kids are the energy that give life to the building. So when [students] weren’t here back in August and September, however many months, it was the loneliest feeling, but now that [students] are back, and I’m seeing more and more of [them], it makes my heart real happy.”

Math teacher Angie Seckar-Martinez has also enjoyed getting to meet her students in person, though it hasn’t been without a few goofy moments.

“Yesterday, when someone who I really should have recognized came in, my mind just went blank,” Seckar-Martinez said. “I had to just admit it and say ‘I cannot place who you are.’ I also have no concept of how tall or short anyone is, which goes both ways. Sometimes I’m like, ‘Wow, they’re tiny!’ and other times I’m surprised at how tall they are.”

Since the “Back to Mac” email, Seckar-Martinez has also changed her set-up to accommodate both virtual and in-person kids. Those in Seckar-Martinez’s in-person classes aren’t required to log onto the Zoom; instead, they follow the document camera that is simultaneously shared on Zoom and on Seckar-Martzinez’s whiteboard.

“I feel bad because I’m like, ‘Who am I making eye contact with?’” Seckar-Martinez said, “but when I give the virtual students asynchronous work time, my attention shifts more to in-person students.”

For Seckar, however, some of the challenges that appear when teaching math on Zoom have been minimized through in-person teaching.

“There are some things that are difficult on Zoom that are easier in person,” Seckar-Martinez said. “For example, the other day, this kid had a calculator issue. So he had to send me a picture of his calculator on Remind and it took five minutes, but in the room, an issue like that takes five seconds. So I feel like things like that are probably less frustrating for kids who are in the room. I can put out those fires really quickly.”

Northcutt believes that, for the most part, the students who have returned to campus thus far are doing so primarily for social reasons.

“I think the most important thing is that the kids are successful and healthy, so if coming back will help with that, you should absolutely come back,” Northcutt said. “But in most cases that’s not who’s coming back. Most of the kids coming back are the kids who were very successful in virtual learning. They’re just social butterflies and want to talk to people and so they’re here to do that.”

Northcutt’s real concerns lie in locating what she calls the “ghost children”: the students who have gone off the radar this year.

“I haven’t seen any of the ‘ghost children’ come back, with maybe one exception,” Northcutt said.

Seckar-Martinez has had a similar experience not connecting to some students through Zoom.

“When I think about algebra, with a lot of the kids in the room, I’m so happy they’re back because they need some more one-on-one help,” Seckar-Martinez said. “Then maybe half of my kids on Zoom are so independent they’ll do well either way. But the other half on the Zoom… they’re just gone. I’m losing them. And I can’t reach through my screen.”

As for whether now is the right time for students to return to in-person learning, Northcutt believes that certain needs should be treated differently than others.

“I’ve said since the fall that if you are not having success at home, and it’s affecting your mental health, you should come back,” Northcutt said. “Do I think everyone should come back? No, that would be dangerous since we couldn’t social distance.”

Northcutt points out that data claiming schools to be safe may not be entirely accurate because up until now, many schools have been mostly empty.

“My biggest class is seven,” Northcutt said. “We’re able to distance and we wear a mask, but if everybody came back at once, it wouldn’t be safe and we all know that. So I don’t want the message that ‘yes, it’s definitely better with people in this building’ to lead people to think that we should have fully reopened from day one. That wouldn’t have been the answer either.”

Gun, however, would be perfectly content to teach to a room full of students.

“Even at the beginning when they told us we had to come back, I was thrilled to come back,” Gun said. “I love my job, I love being here. I didn’t realize how much I was going to miss [students] until I was here all day long with 30 empty desks, and then it kind of made me feel sad… [For] me… just because I’m selfish, I want all 36 kids here for the hour and a half because I think you get more done. You have [fewer] distractions, and I can teach more, and I can focus more on what we’re studying.”

Gun, like Northcutt, is seeing that the students who are primarily returning to the classroom were doing well at home without any extra support, but are coming back instead for the social aspect of in-person learning. Still, Gun raises the concern that the students who should be coming back to get extra support are not.

“Some of the kids that I wish would come because they’re not getting anything–and I’m mostly talking about freshmen–they need to come back, because some of them are really struggling,” Gun said. “This means that if they fail most of their classes this year, they’re going to repeat freshman year. So something’s wrong with that. … In my freshman class, 75 percent, maybe 80, are doing great. But I’ve never had this many failures in Spanish 1.”

In hindsight, Northcutt believes that the “answer” to the virtual vs. in-person debate was to prioritize the “ghost children” who have fallen off the radar.

“Who’s looking for the ‘ghost children’? Who’s knocking on their doors? I need somebody to help me find them,” Northcutt said.