“He loves me…he loves me not” goes the age-old childhood game, also known as effeuiller la marguerite, which originated in France long before the thought of social media was born. The game involves picking petals off a daisy to find out if one’s love interest loves them back. But now it’s mostly a cliche, played by 9-year-olds hoping to figure out if their third-grade romance will blossom into something more than awkward eye contact and sharing animal-shaped erasers. The idea of the daisy’s equivalence to young love dates back millennia as poets and authors continue to use the reference in modern writing.

In today’s world fueled by the Internet and Buzzfeed quizzes, there is an app to tell you if you and your crush are compatible or the exact age you will be when you meet your soulmate. The daisy has survived as a symbol of childhood innocence but it’s taken on an entirely different context in the colorful high-tech world of social media. Project Daisy is the name for the movement to eliminate public like counts on the social media platform Instagram.

Under the new management of Adam Mosseri, former overseer of the Facebook news feed, Instagram may undergo substantial and controversial changes. Mosseri came to Instagram in October after founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger clashed with Instagram’s parent company, Facebook and its chief executive Mark Zuckerberg. With the split, dozens of employees left and the two once separate entities became connected by teams of engineers and project managers intent on rebranding Instagram to the subsidiary-sounding “Instagram from Facebook.”

Skeptics had a field day with the news of Mosseri taking over, as obsessive Insta users were concerned if the relationship with Facebook would tarnish the app that has created a generation full of hashtagging, selfie-taking, influencer-aspiring social-media production and consumption machines.

In an interview with Amy Chozick of The New York Times, Mosseri said he kept being paranoid that the world would turn into an episode of Black Mirror, the satirical dystopian anthology series about tech-disasters. One particular episode haunts Mosseri in which characters rate each other on a scale one to five stars leading to devastating consequences.

Likes are seen as the underground social-media currency that affects everything from cooking videos to the influencer community to the next celebrity pregnancy scare. While the Instagram is assessing the permutations of the effects of Project Daisy, the “dogfooding,” internal tech slang for testing, process is being tested out with a selected group of users.

Mosseri hopes that the implementation of this new plan will show the world that Instagram has learned from the pitfalls of its parent, Facebook, and that Instagram is taking steps towards recognizing and helping its users ameliorate the highly corrosive pain that can accompany social-media use.

The company has not decided whether or not it wants to eliminate counting likes entirely. It may indicate when a post becomes hugely popular by indicating that it has passed a benchmark number: tens of thousands of likes or hundreds of thousands of likes as examples. But this decision will not affect the average teenager would never approach that threshold and is more worried about that “day at the beach” post being liked only by close family members.

“We should have started to more proactively think about how Instagram and Facebook could be abused and mitigate those risks,” Mosseri told Chozick. “We’re playing catch-up.”

The company is trying to make “a less pressurized environment” with users being able to see who likes their own post but not the like count of other people’s posts. Their goal is to stop the comparison and make Instagram feel like less of a competition.

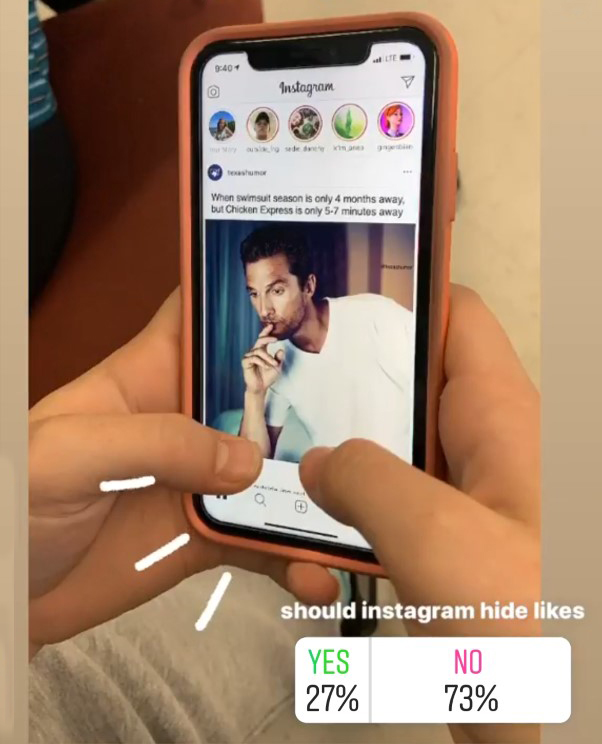

In a poll on the MacJournalism Instagram feed, 27 percent of the 327 followers who responded said that Instagram was doing the right thing by hiding like counts. The vast majority of respondents, 238 (73 percent), voted that Instagram should leave like counts visible on all posts.

Senior Kathryn Chilstrom was in the minority supporting Project Daisy.

“Social media is damaging enough,” Chilstrom said. “Having a certain number of likes on a post is very detrimental, sometimes even without us knowing it.”

The potential impact is significant considering how much time teenagers spend on social media. According to a 2015 Pew Research Study, 92 percent of teens go online in some way every day, and 24 percent of daily users are “constantly on social media” to the point where they consider it a full-blown addiction.

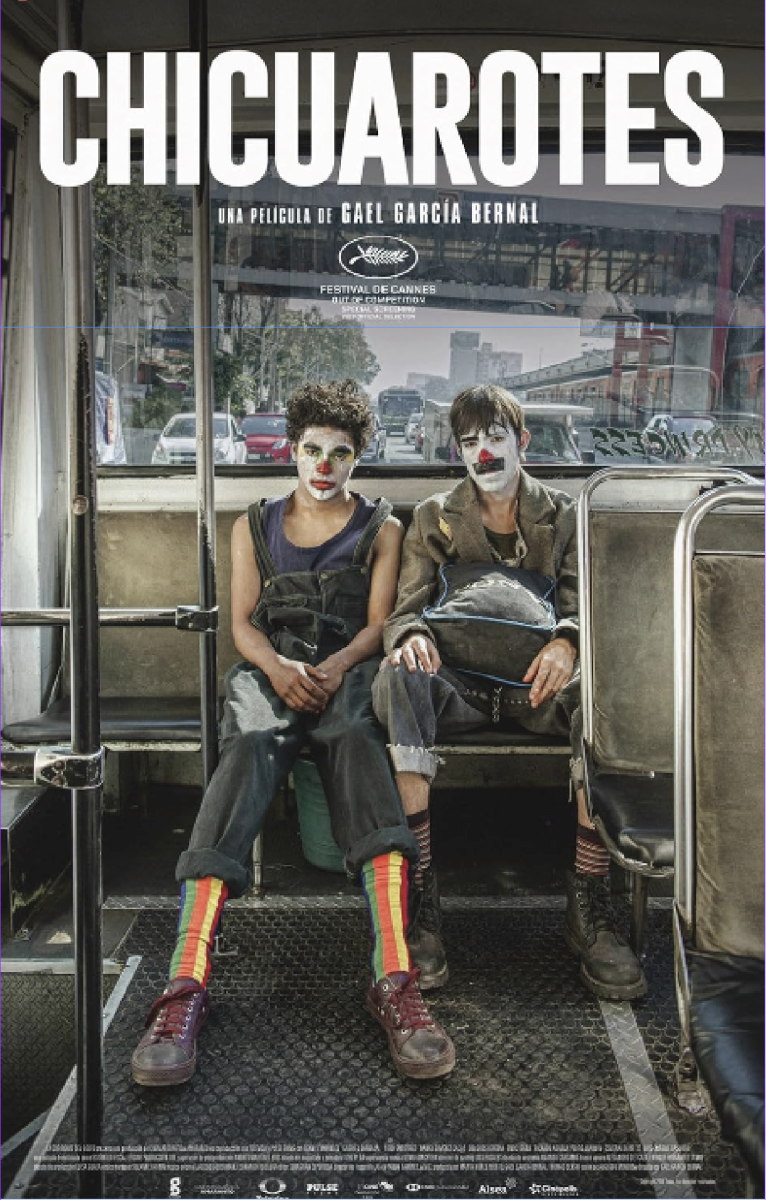

The issue of social media addition has even found expression in mainstream entertainment. In the 2017 film, Ingrid Goes West, director Matt Spicer and his co-writer David Branson Smith created a movie concept based on actual Instagram stories they followed. In the film, a mentally unstable young woman portrayed by Audrey Plaza squanders her recent inheritance in the pursuit of a seemingly perfect Instagram obsession played by Elizabeth Olsen.

Spicer said in an interview with Indie Wire that he hoped the movie “led to a larger conversation about Instagram and the effect it has had on our culture.’’

The film also explores the umbrella topic of much of the socializing done in our lives that revolves around digital platforms.

According to Smith, the movie’s protagonist relies on social media as a “way of interacting with the world, building a community and building friendships, but it’s made of nothing. She’s the manifestation of our worst impulses on social media.”

The same reliance on social media in the real world, finding a person’s self-verification and worth through social media, is what prompted Mosseri to launch Project Daisy.

Junior Matthew Vargas says he understands the social media harms that Project Daisy is trying to address.

“People can use social media to hide behind a mask that they have created by the content they post,” Vargas said. “For example, if someone is posting all these photos of them on vacation and having a good time, they’re only showing you ‘the truth’ about what they want you to see. You aren’t really able to see the true things happening behind the scenes.”

Vargas, a decorated Blue Brigade officer and McCallum dance major, sees a utility for social well beyond seeking the validation of likes. He utilizes social media to showcase and market his dancing career.

Using the platform Instagram, Vargas shares his solos and dance routines and says that if there wasn’t social media, it would be very hard to get his name and his dancing out into the world. He stresses that he does so because you never know who might come across your social media account and offer you the opportunity of a lifetime. Vargas thinks that likes should stay visible to all but that people must be cognizant of their social media usage.

Junior Alex Melendez agrees with Vargas that Instagram and other social media platforms can be used to connect and communicate effectively with others. Despite acknowledging these benefits, however, Melendez also fears that social media can negatively affect teenagers’ mental health with exclusion and cyberbullying.

“People can get very addicted to it and when someone sees others post on Instagram getting more likes and comments, it can cause feelings of depression and self-depreciation,” Melendez said. “It also is a vehicle for cyberbullying because you can be anyone behind a screen; it’s not face to face.”

As Instagram is testing out this new format it is unclear when this appearance will be rolled out for all users.

“I almost feel like this would be worse,” Vargas said. “By taking away the Instagram likes, you’re taking away the feedback from someone’s posts and the validation certain people get, for some people that’s the only thing to help them along with nice comments and encouragement on the posts.”