High school has always been a time for teens to experiment, test limits and break boundaries. However, some poor decisions are much more serious than sneaking out late or cutting a class or two. Even though it is often not reported, sexual harassment is an issue at McCallum, at high schools across the nation and in adult life as well.

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission defines sexual harassment as “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature … [that] explicitly or implicitly affects an individual’s employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work performance, or creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment.”

Because not everyone defines sexual harassment the same way, it can be difficult to discipline sexual harassers.

“I have had students in my office who have openly discussed with me being groped by another student, being called certain names or being catcalled,” guidance counselor Mickey Folger said. “It seems to me that the largest issue seems to be inappropriate touching.”

One female student said that during the fall semester she was physically harassed when getting food from one of the vending machines in the breezeway.

“Someone asked me if they could borrow a dollar, and I said no, and by the time I turned back to the vending machine, someone was grabbing my neck and kissing me on the back of my head,” she said. Because she could not identify the person who harassed her, she did not report the issue and wishes to remain anonymous.

“When I turned around to see if they were there they were gone.”

She said the experience has affected how safe she feels at school.

“It makes me feel weird when I’m walking in the hallways alone.”

Another student claims that she has been harassed by a group of students for months but has not reported anything. She is not sure if she will, so she requested anonymity.

“It really hurts me because there’s not anything I can do to stop it,” she explained. “I’m basically being objectified in a way that I can’t do anything about [it].”

For McCallum students, the punishment for committing sexual harassment is fairly severe.

“I can tell you, based on my experience, that [offenders] would be removed from school,” Folger explained. “They would be required to go to ALC for 21 days, and they would have to go through some [sexual harassment] classes there with their parents before they would be allowed to come back to campus.”

In the long run, the consequences go even further.

Kate Carmichael, a licensed professional counselor who specializes in working with adolescents, said the consequences can be life-altering.

“If you are a perpetrator of sexual trauma you can face jail time, probation and community service, as well as a permanent record where the incident will follow you for the rest of your life, making it difficult to find jobs, apply for loans or buy a house.”

Although the consequences are serious, Carmichael said that some students face social pressure that also strongly influences their behavior.

“There is pressure to be sexually active and ‘cool,’ which means having many sexual experiences by graduation,” Carmichael said. “This kind of pressure is also insidious and hard to identify as it is happening in a group. It can feel isolating and shaming if you don’t feel you are far enough along sexually, which causes low feelings of self-worth.”

One McCallum student said he has witnessed these pressures firsthand.

“I think [harassment] is [a] normal [occurrence], but it shouldn’t be,” he said. He claims to have witnessed many of his friends talk about and treat women with disrespect. Although he wishes to remain anonymous to protect his friends, he does not support their behavior.

“The culture that we’ve established, the media saying what guys can and can’t do, is influencing all this behavior.”

Carmichael also stated that some harassers might hurt others as a way to heal themselves.

“Many offenders have been abused in some form in the past as well and act out on others as a way of managing untreated trauma,” Carmichael explained.

The current generation faces a new challenge when it comes to sexual harassment: social media. Now, it is easier than ever for anyone to become a victim or an offender, and unlike in person, messages over social media can be erased with the swipe of a finger, and consequences are much less likely. When it comes to minors, this form of harassment can be very dangerous. If a student is sexually harassed over social media, what they do in response can lead to legal issues on both sides, possibly felonies.

“[People] are less scared to say things over social media because they won’t get as harsh of a reaction,” said one student who told The Shield she is sexually harassed in person and over social media every other day.

Around the beginning of the school year, she started getting regular Snapchat messages from another student that she didn’t know very well.

“He Snapchatted me and told me that I was luring him in, then he told me, ‘You should send [pictures],’” she said. “He tried to make me feel sorry for him.”

These messages made her uncomfortable, but because she sees him at school regularly, she has not reported the issue and requested to remain anonymous.

“Maybe I should report it, but it’s just how it is,” she told The Shield. “I’ve accepted it at this point.”

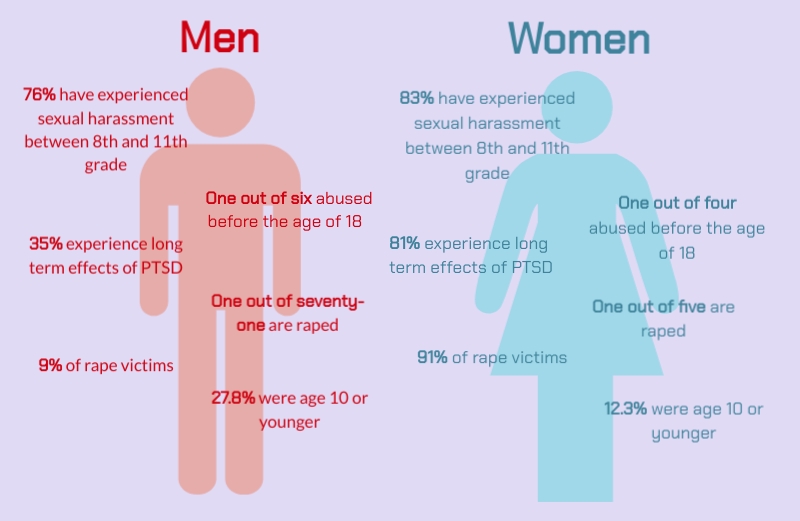

In a 2002 survey conducted by the American Association of University Women on 2,064 students in eighth through 11th grade, 83 percent of girls and 78 percent of boys claimed to have experienced sexual harassment at some point in their lives. If this is such a prominent issue in society, then, why do so few people report it?

“Many do not ever speak about the event for fear of being shamed further,” Carmichael said.

She told The Shield that many of the teens she has talked to who experience sexual harassment deal with trauma long after the incident.

“[They] often bottle up these feelings, causing other side effects such as self-harm, drug dependence, isolation, anxiety and depression,” she said. “Untreated sexual trauma causes difficulty forming healthy relationships with others, a lack of trust in relationships, and, ultimately, further feelings of isolation and loneliness.”

Oftentimes, Carmichael states, the punishment for the offenders is not what concerns the victims when they are considering coming forward. They are more concerned with their own consequences.

“As a victim,” she said, “you will have to face the emotional pain of navigating a legal system that is often not well-organized and can be re-traumatizing as you are asked to recount your story over and over.”

In some cases, students do not think that talking to an adult is necessary or that adults can offer the right kind of help.

“I don’t think that going to a trusted adult is necessarily the right move, just something you’re told to do,” a student who claims to be a victim of sexual harassment told The Shield.

Nonetheless, Folger and the other guidance counselors encourage students to come forward if they are having these issues, even if they feel uncomfortable talking with an adult.

“I think that there’s a level of shame that comes with opening up to an adult,” Folger said.

She and her fellow counselors are trying to break that stigma.

“Use your voice. Articulate your boundaries. Be firm in them,” Folger said.

According to the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, sexual harassment can be interpreted as child abuse and failing to report child abuse is against the law. In encouraging people to report harassment, the department also points out that if someone reports an incident with good intentions, they are not legally responsible if the report turns out to be untrue.

Whether or not the incident is reported right away, Carmichael urges anyone who knows someone who has been a victim of harassment or violence to listen to and support them.

“Becoming a safe person to talk to allows people to share and find the help they need,” she said. “Know the signs of sexual abuse and talk to a safe adult. Nobody needs to navigate this time alone.”

—with reporting by Kennedy Weatherby

Barri Rosenbluth • Mar 9, 2020 at 3:07 pm

Dear McCallum Community,

We’re pleased to see this important issue being addressed in the Shield. We would also like McCallum students, families and faculty to know there are resources on campus to support students who have experienced harassment or abuse and an AISD complaint process https://www.austinisd.org/respectforall . Expect Respect, a program of the SAFE Alliance, began at McCallum High School 30 years ago and currently serves over 50 Austin-area schools. The program offers school-based groups and counseling for students who have been harassed or exposed to other forms of violence or abuse. It also provides educational theatre, youth leadership development and professional training on preventing and responding to sexual harassment at school. Resources for educators are available on our website at https://www.safeaustin.org/our-services/prevention-and-education/expect-respect/resources-for-educators/. For more information please contact us at [email protected].