Speak Visually. Create an infographic with Visme

Data collected from Austin ISD reports from the 2015-16 school year.

My life outside of school is dominated by white female literature. My mom, who fell in love with Jane Austen novels so much that she named me after one, taught me how to read with the critical lens of historical context. Virginia Woolf, one of my favorite female writers, is revered throughout the literary world as a champion of the modernist stream-of-consciousness style. She, along with other women writers of the aristocracy, undertook what little privilege they had due to their class and race to produce literary works that are still recognized today. Many white women, the most famous being the three Bronte sisters, had to write under male pseudonyms in order for their work to be published and recognized in the literary world.

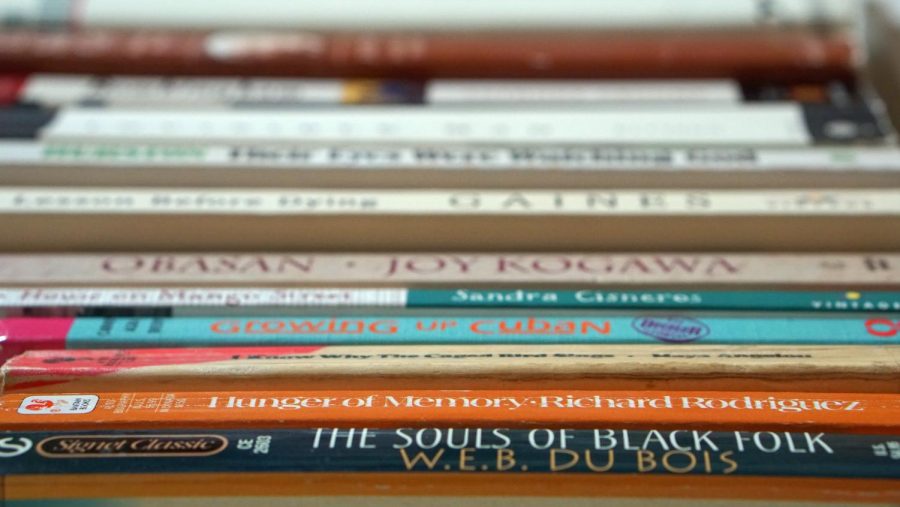

Despite all of this hardship, white female authors were the lucky ones. Today, white women authors have become more widely recognized and accepted throughout the literary canon. Now that the gender gap is slowly closing, more of an effort must be made to expand the literary canon to authors of color. Out of the 43 books McCallum students read in English class, including AP and regular English classes, eight were written by authors of color. This imbalance is caused by a combination of factors, specifically the problems that authors of color faced in a publishing world that was dominated by white men for most of modern history. Diversity in authors of the books taught in school expose students of all genders and races to the ideas and perspectives needed to better understand the world around them. Being white myself, hearing about issues faced by communities of color from authors of color leads me better able to understand issues that I will never have to face.

The canon of literature is dominated by books that are riddled with themes describing the great American experience. Depictions of war, poverty and southern idealism run rampant in English classes throughout the country, leaving little room for books about the marginalization of minorities. When these themes are included, they often appear in works by white authors, who gloss over the issue of racism with vague descriptions and subtle allusions.

Some say that it is not the author of the book that matters, but the content of the book itself. While I agree that content should be a determining factor in assessing the literary merit of a piece of writing, it also is a gross oversimplification to ignore other factors that affect the literature we read. Without questioning lack of author diversity, it becomes easy to brush the problem of the over-representation of white male authors aside. Authors of color face opposition in the writing and publishing world. For this reason, it is harder for authors of color to gain the same level of recognition in the canon of literature as white authors.

For example, Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad, a highly revered book in the literary world, originally caused controversy for the light it shed on European mistreatment of the Congolese. It wasn’t until half a century after it was published that the book was criticized with claims that it dehumanizes the Congolese with racist depictions. Nigerian author Chinua Achebe wrote his book Things Fall Apart to tell the story of European colonization of Africa from the perspective of those who experience it, rather than using the narration of a white outside observer as Conrad did. Whether or not you agree that Heart of Darkness has racist undertones, the need to include authors of color in the literary canon is apparent when white authors have written the narrative of progressive literature for most of history.

One of the books that stood out to me the most out of all of the prescribed AP literature I have read in my time at McCallum was Beloved by Toni Morrison, who in 1993 won the 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature. She was the first black woman to receive this award. The reality that she is one of the only three black female writers whose work is taught at McCallum is astounding. Morrison, with her complex narrative and vivid imagery, was a powerful wake-up call for me to realize how little of a voice black women have in the literary canon.

The simple truth is that authors writing about issues that pertain to race, class, and gender all offer unique perspectives, but authors that have experienced these issues firsthand have more individualized authority to tackle them. Students reading literature that speak to truths they often face in their daily lives are more inclined to make personal connections to the books they read. Over half of McCallum’s English students are students of color, but only 19 percent of the books taught in class are written by authors of color. This disparity is a problem that needs to be addressed.

For high schoolers forming opinions on the world around them and making decisions that will greatly impact their future, representation in their education matters. Today, there is more of an effort being made to promote diversity in authors and their stories both in the classroom setting and in the literary world in general, but more still needs to be done. There never was and never will be a shortage of talented minority authors, only the lingering refusal to accept that the literary canon was formed by a system that is biased toward white male authors. The ability to correct this bias starts in school. Even though McCallum’s English department is better than most at teaching books from a diverse pool of authors, there is still a long way to go.

Grace Van Gorder • Oct 6, 2018 at 2:13 pm

I completely agree with the message of this article and I had no idea about the shocking statistics involving AP class readings even in our own school. The fact that the percentage of colored students and the percentage of colored authors does not line up even a little is really shocking.