“The stars at night are big and bright, deep in the heart of Texas.”

Most McCallum students and people in Texas are familiar with this song, which is performed before UT football games by the band, sung at countless elementary school talent shows, and played during the seventh inning stretch of baseball games. But many students aren’t familiar with the actual stars mentioned in “Deep in the Heart of Texas.”

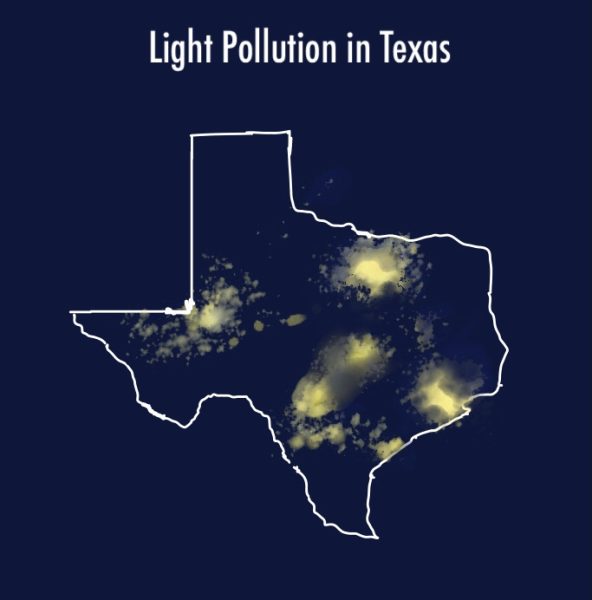

A study published in Science Advances estimated that 80% of Americans will never see the Milky Way in their entire lifetimes. And that number will only increase as light pollution grows globally by 10 percent each year.

Austin is not excluded from that statistic. As a matter of fact, light pollution may have increased faster in Austin than in other cities as its population has grown tremendously from 251,808 residents in 1970 to 984,567 residents in 2024. Joyce Lynch, vice president of the Austin Astronomical Society, has lived in Austin for fifty years. In that time, Lynch’s society has been forced to relocate star parties and astronomy nights due to poor visibility in Austin.

“We used to have a place out on Bee Caves Road where we would go for observing,” Lynch said. “We haven’t done that for a long time because we can’t see that much there. We keep having to go farther and farther out from Austin.”

The Austin Astronomical Society currently hosts star parties out in Pedernales Falls, which is around an hour and 15 minute drive from McCallum. While the stars there are far clearer to see than in Austin, it’s still difficult to see the Milky Way or observe objects that are close to the ground even on the clearest nights due to the glow of light on the Eastern horizon.

One way to see stars is to travel to DarkSky locations. DarkSky International certifies different towns, national parks, and remote areas where it’s possible to see beautiful stars as International Dark Sky Communities, Parks, and Sanctuaries. McCallum sophomore Dede Reagins got the chance to go to one of these locations, the Grand Canyon, in eighth grade on a school trip. For Reagins, the experience was eye-opening.

“It was really my first time being able to see the stars on such a greater scale,” Reagins said. “It helped peak my interest in light pollution because I really noticed a difference. It’s a very rare experience that I had and it makes me a little bit upset because it’s such an interesting topic.”

As Reagins acknowledged, many students don’t get the chance to see stars. The closest Dark Sky Preserve to McCallum is the Greater Big Bend International Dark Sky Preserve, which covers 15,000 square miles of the Chihuahuan Desert and extends from West Texas into Northern Mexico. It is at least a six hour drive from Austin to Marathon, a town at the edge of the preserve, and other areas near the preserve’s core are even more distant.

“People don’t necessarily want to have to travel a long distance,” Lynch says. “They want to be able to see what’s going on in the sky without traveling too far.”

Even for those who have had the chance to travel to dark sky locations, students can’t see the stars on a daily basis.

“When people don’t see the stars or the planets in the sky, they feel like it doesn’t have any impact on anything they do in their daily lives,” Reagins said. “It makes me feel really sad that something so interesting could be so lost.”

Light pollution doesn’t only hurt visual astronomy. It also impacts the environment, according to DarkSky International, which estimates that 1 percent of total carbon dioxide emissions are produced by unnecessary light pollution. That means that light pollution emits about the same amount of greenhouse gases annually as driving 49 million cars for a year.

Light pollution also has a very local impact. Annually, two billion birds migrate through Texas, one third of migrating birds in the spring and one fourth of migrating birds in the fall. These birds are often attracted and disoriented by the lights of skyscrapers, causing them to crash into these buildings and die. A study published in the Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics found that almost a billion birds die because of hitting lit-up buildings at night nationally.

Jennifer Lueckemeyer is an environmental scientist and ornithologist who studies and protects golden-cheeked warblers, an endangered species only found in Central Texas. While the golden-cheeked warbler is at less of a risk from hitting buildings than migratory birds, Lueckemeyer has noticed and feels for the loss of migrating birds due to city lights.

“Light pollution can be very harmful to migratory species,” Lueckemeyer said. “It’s terribly sad to know that birds are having these strikes with glass. They die a horrible death when they strike glass.”

To combat light-pollution induced deaths, the Houston Audubon Society founded the Lights Out Texas program, which encourages homes and businesses to turn off unnecessary lights at night.

“I think that people don’t often realize what they have control over: their own house and their own backyard and front yard,” Lueckemeyer said. “Turning off the lights there can make a huge difference in bird migration.”

Lights Out Texas also recommends closing blinds at night, using motion detectors so only lights only turn on when necessary, aiming streetlights toward the sidewalk and capping them, and replacing whitish blue bulbs that emit a color temperature above 3000 degrees Kelvin with warmer, red-orange bulbs.

These are some of the same policies that DarkSky International requires its International Dark Sky Communities to maintain. One of these communities is Flagstaff, Ariz., which was established as the first ever Dark Sky Place by DarkSky International in 2001. Sophomore Lucy McTeague lived in Flagstaff for three years in between fifth and eighth grade, and enjoyed being able to see the stars anywhere in the city.

“If you just look up, no matter where you are, you’ll see so many stars,” McTeague said. “It’s really cool because in most cities, it’s really hard to see the stars because of light pollution, but in Flagstaff, it’s designed so you can because it’s a dark sky city, so the stars are really beautiful.”

In addition to enhancing the view of the cosmos, having light pollution reduction strategies in place like those in Flagstaff could also benefit local businesses. According to a study conducted by DarkSky International, 99 percent of outdoor light is wasted, which means that $50 billion is lost to unnecessary lighting a year.

“Money talks, and that’s one way to appeal to businesses: not just to appeal to their sense of doing right by the animals and the astronomers, but knowing that it’s going to save them money,” Lynch said.

To save money, Austin ISD already requires that McCallum teachers turn off the lights in their classrooms, according to astronomy teacher Ivan Gonzalez. Additionally, there are currently no large sports lights on campus, which means that light pollution is already greatly reduced compared to bigger schools.

Due to light pollution from the rest of the city, however, it is nearly impossible to see anything but the brightest stars at night. To change this lack of visibility, Gonzalez suggests that the community should only use lights when necessary at home.

“Use them wisely,” Gonzalez said. “On a small scale, as an individual, just turn on lights when you actually need them.”

In 2003, a specific week—International Dark Sky Week—was founded for this very purpose by Jennifer Barlow, who at that time was a high school student in Virginia. According to DarkSky International, International Dark Sky Week’s purpose is to “draw attention to light pollution, promote simple solutions to mitigate the issue, and celebrate the irreplaceable beauty of a natural night.” International Dark Sky Week is coming up this year the week of April 21-28.

Reagins feels that students should learn about light pollution, whether on their own or through events like International Dark Sky Week.

“I think that we should all study light pollution more and as a community find ways to make it better for everyone,” Reagins said. “I feel like if we work together to solve the light pollution problem then we could make it so that we can see the stars at night and that would be really beautiful.”

Isa Truan • May 12, 2025 at 2:25 pm

Light pollution is a growing issue, especially in a big city like austin. Thank you for spreading advocacy about this issue when so many people forget that it surrounds us everyday. I’m glad you included smalls ways we can each contribute to this larger issue.

Hunter Parker • Mar 12, 2025 at 2:58 pm

Light pollution is a critical issue in many urban areas across the world. I liked how you kept it informative while helping the reader stay engaged. I appreciate this story and I really enjoyed it.

tzuri • Mar 6, 2025 at 9:06 pm

I think light pollution is a very important topic, and I’m glad to have gotten to read about it. I love all the images you included, they helped the article feel more engaging to read!

Lilah Lavigne • Mar 4, 2025 at 12:32 pm

Great job Elisabeth! This really makes me rethink the subject of light pollution. I’m going out to Big Bend for spring break, I’m excited to see the sky without all the light pollution in it. Thanks so much for sharing all the intriguing info!

milo • Mar 4, 2025 at 8:11 am

This story is great and really well written and it covers very important issues.

Harriet • Mar 2, 2025 at 8:14 pm

I go camping a lot and I always try to look up at the stars during the night, and I feel lucky to have seen the milky way several times. My favorite Dark Sky places to go are Enchanted Rock, McDonald’s Observatory/Davis Mountains State Park, and Big Bend! This was a really great article, great job!

Edie Davidson • Feb 25, 2025 at 6:45 pm

I think this was extremely well-written and a great topic because of Austin’s huge air pollution issue. Great job!!

Lillian Gray • Feb 24, 2025 at 8:38 pm

I love this article Elizabeth! It’s so informative. Good job. 👏👏

Grace • Feb 24, 2025 at 9:55 am

It is very hard to see stars in Austin, I always only see them when I am out in the wilderness very far from the city. It sucks because stars are so beautiful and it is very rare to see them nowadays.

lucy • Feb 24, 2025 at 8:58 am

I really like the countdown that is included, it makes it seem more fun.