Your donation will support the student journalists of McCallum High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

AISD: a segregated district, then and now

The reasons for the racial divide are as numerous as the ways in which it shapes the student experience

March 26, 2018

Though Leander Thompson’s parents were in and out of jail frequently when he was a kid, he always managed to push himself to succeed in elementary school. When he got to middle school, however, his academic life went downhill when he noticed something about himself.

“Middle school was when I became aware that I was noticeably different,” Thompson said. “It was not until the first day of middle school that I realized I had to officially split from my elementary gang. I went from being a straight-A student to an F student. Not because I was dumb but because I was unhappy.”

Thompson had gone into his honors classes looking for his friends to sit with, but he soon realized that now, his was one of the only African-American faces in the room.

“I had no friends to relate to,” he said. “I felt like everyone looked down on me. Not having class with my friends encouraged me to be late all the time just to walk them to theirs. During passing periods me and my friends would walk around the whole school just so I did not have to be on time. Coming into the magnet program I was already behind because I never got the memo that we were assigned to read a memoir. I had never even heard of doing homework in the summer. When it came to buying materials for big projects, I was late getting them because we did not have a car. Everything in general was more difficult.”

Unfortunately, Thompson’s story is a familiar one across the nation but particularly in Austin.

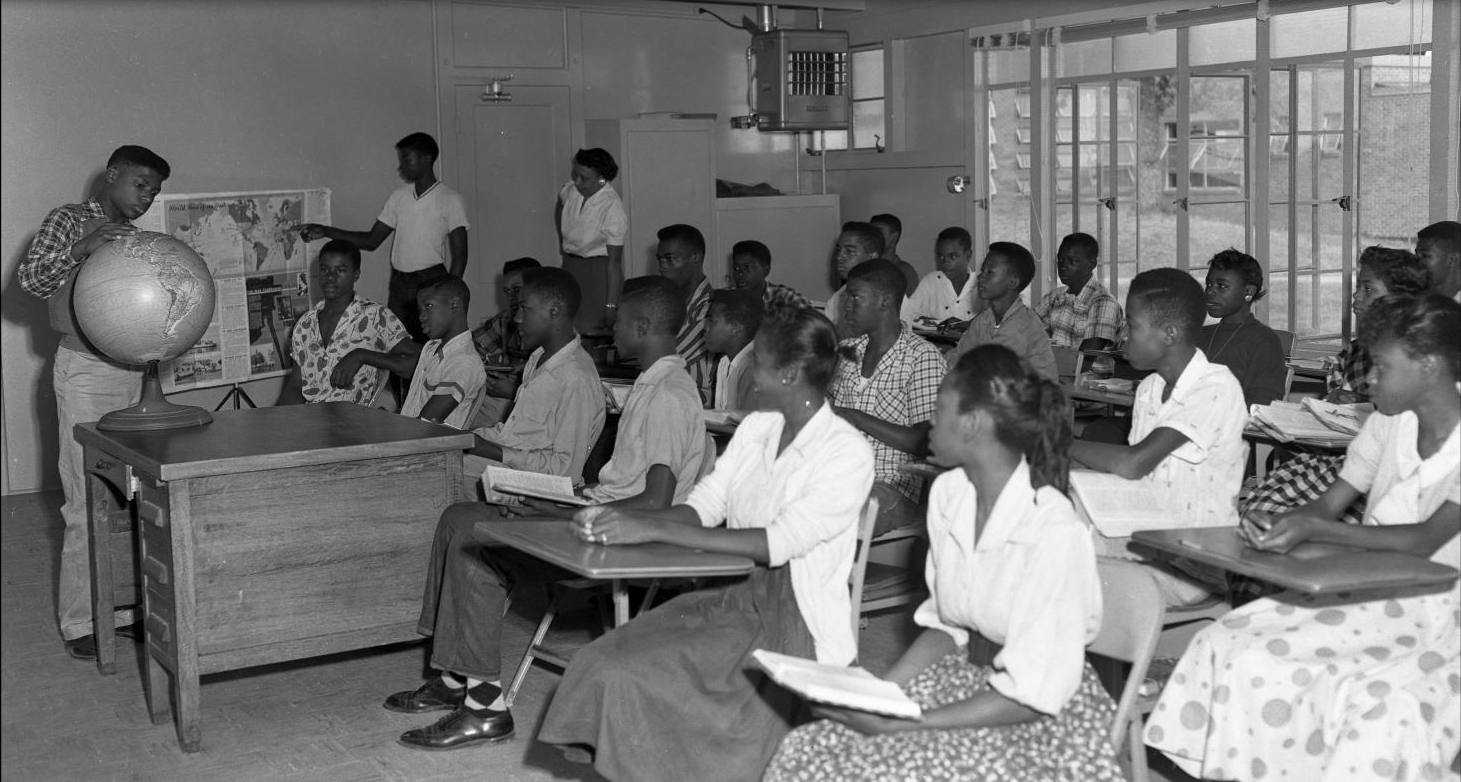

A history of discrimination

March 22 marks the 90th anniversary of Austin’s infamous Koch and Fowler city plan. The city of Austin adopted this plan in 1928, and it designated an area east of Interstate-35 as Austin’s “Negro district,” establishing most of the city’s segregated facilities there in an effort to push the black population into the area. An area south of the “Negro district” was similarly designated for Hispanic families.

The high school designated for African-American students was the original L. C. Anderson School. Its campus now hosts the Alternative Learning Center.

In the early 1900s, as Austin’s Latino population grew exponentially, AISD established multiple schools for Spanish-speaking children, first and foremost the West Avenue School, which remained in operation until 1945. Superintendent A. N. McCallum, spearheading the school’s opening, responded to protesting parents by saying that the “children were not transferred because they are Mexicans, but because their inability to speak English makes them an impediment to the progress of the English speaking children.”

Historians at the Austin History Center have since suggested that the schools likely targeted students based on their Mexican ethnicity, rather than the primary language they spoke. Those with Mexican-sounding surnames were segregated into the schools regardless of what language they spoke. Civil rights lawsuits in the 1970s found that Austin had intentionally discriminated against Hispanic children on the basis of ethnicity, arguing that “a benign motive will not excuse the discriminatory effects of the school board’s actions.”

The AISD school board order that schools be integrated came in August of 1955, as 12 black teenagers were the first to integrate Austin’s schools; one enrolled at McCallum, five at Travis, and seven at Austin High. The first student to integrate McCallum was Margie Hendricks, then 15.

Austin’s desegregation order was lifted in 1980; afterwards, the city no longer was obligated to use busing or any other initiatives to proactively promote integration. Some social scientists have argued that rescinding integration court orders prompted many cities across the country to rapidly resegregate.

What segregation means for students and schools

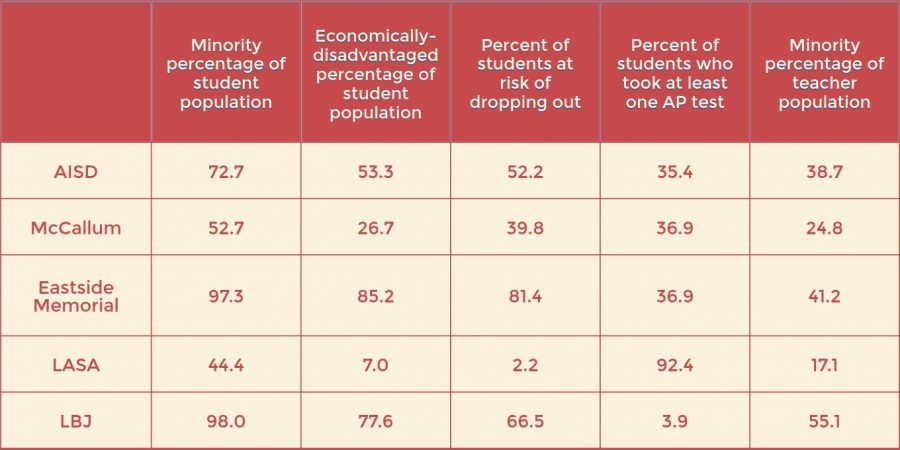

Schools that are segregated by race and income are far more likely to underperform academically as opposed to whiter, wealthier schools, a concept known as the “achievement gap.” For example, in 2017, a third of black and 40 percent of Latino students passed a statewide standardized test, while 80 percent of white students passed that same test. Similarly, 53 percent of white students who took at least one AP class passed the test, opposed to two percent of black students and 33 percent of Hispanic students, according to district data.

AVID, or Advancement Via Individual Determination, instructor Elida Bonet says that one of the harder parts of supporting her students of color is encouraging them to take AP classes.

“If you’re not doing pre-APs and APs, college is going to be really hard,” Bonet said. “We really need to push our students to be in those classes, but then make sure that those classes are welcoming for them because the major complaint that comes out of their mouths is, ‘I’m the only person of color.’ Last year, we did something; we had a student who was the only one in her class. It was pre-AP, and she said, ‘I’m the only one there; nobody talks to me, when they say to work with somebody, nobody asks me to be in their group,’ and I had two other students who were in the same class, but at a different period. So they were like, ‘Why don’t you switch to our class so we could all three work together?’ So we did… and she did pass the class because they had a cohort, other people she could ask for help without feeling dumb.”

Though in many states, districts spend more per pupil on disadvantaged student populations, low-income and minority students are still more likely to have inexperienced teachers and a greater teacher turnover rate. There is a general consensus that poorer school districts must pay more to attract teachers to compensate for reduced school safety, leadership stability and availability of support staff.

“We call it an achievement gap, but the reality is… if you look, there’s a question to be asked as to, ‘Who is given what level of instruction? Where do the most experienced teachers teach school-to-school, and within a school? Who do they teach?’” Dr. Foster said. “There’s a quality of the circumstances surrounding the students that reframe the conversation a little bit.”

A study from the Center for Public Policy Priorities found that black and Latino children in Austin are more likely to attend low-income schools, live in poverty, have fewer teachers with experience and be malnourished. One in three black children and one in four Latino children in Austin live in poverty; meanwhile, five percent of white children and four percent of Asian children do. 61 percent of black and 52 percent of Latino children attend schools with high teacher turnover rates.

Bonet says that many socioeconomic factors beyond students’ control can negatively affect their achievement.

“If you’re hungry, then your brain is just not working well,” she said. “If you don’t have a way to get to school because for some reason they have to be brought to school, but mom and dad are working, and they aren’t off at the time and they’re coming in late, or they’re using the bus, so you are not having consistent transportation. Having to work. That is a huge one that I don’t think we realize even as teachers, the impact that has. We have so many students who work not just to be able to go to the movies and to go for dinner, [but] they’re working because they’re pretty much supporting their entire families. We don’t realize–I don’t think I ever realized until I started working here with the AVID students–I had kids working 40 hours. And they’re not doing it just to buy the fancy shoes, they’re doing it because they’re paying for their car, they’re paying for their phone, they’re paying their insurance, and they’re helping with meals. … Then another part that has influence is if you read as a kid, you develop a love for reading, and even if you don’t love it, at least you read well. But if you’re not a good reader, you pretty much are going to have a really hard time in school.”

An AISD policy allows parent-teacher associations to raise funds for their schools privately, which ends up primarily benefiting high-income, majority-white schools, helping to add even more extracurricular activities, supplemental programs and experienced staffers. Higher-income parents have more time to devote to their school, and often wield more knowledge and influence that they can use to advocate for their children.

Additionally, more affluent parents tend to have children who remain affluent later in life, while children in low-income families tend to remain impoverished. One reason for this rigid divide could be a different level of support: 80 percent of children raised by parents who earned college diplomas report that they were encouraged to attend a four-year college, while only 29 percent of first-generation students say the same.

Bonet reiterates that teachers and administrators need to consider the out-of-school factors that may keep students from succeeding.

“There’s so many tentacles to it; you have to hit it from all these sides,” she said. “Basic food, shelter, because if many of those are missing or not adequate, the student is not well-prepared to come to school. What experiences have they had that we take for granted? I think sometimes we think every parent reads to them, takes them to the museum, takes them to the park, does arts and crafts with them and all these things, but that’s not happening in every home.”

Jonathon salama • Sep 7, 2019 at 9:41 pm

My hope that we look deeper at solving this problem not just talking my daughter did not get in kealing. From Maplewood she is a minority and excellent student very unfair the school should Admit half of the students from east side .

Theodore • Mar 29, 2018 at 7:13 pm

Very refreshing and encouraging to see such an informative, real article being written and published. Informed and informative journalists are the first step to true progress.

Janssen • Mar 28, 2018 at 2:40 pm

I appreciate how honest and informative this article is, even though it’s a sensitive topic

Vanessa • Mar 28, 2018 at 2:11 pm

Great information and for bringing to light our ugly past so that we are constantly working to improve upon it. If we don’t know where we came from, we don’t know where we’re going. We need to consciously and intentionally move forward so that we’re not repeating the same mistakes of the past. With so much youth and gentrification in this city, we sometimes impede unconsciously on our history and make it worse for those that were most affected by this racial bias in the first place. We ALL have to move consciously forward and challenge and change even the institutional establishments that we’re still abiding by. This includes admin, teachers, parents, kids, and residents. IMHO if we’re pulling out our kids out of public school into charters or private institutions, we are not addressing the problem at hand. I realize that ultimately, parents will do what’s right for their own child and what makes sense, I get that, but our kids don’t learn in a vacuum…we learn in a community of diversity, a community of unjust decisions, and we need not only voices to be advocating for what’s equitable in the public school system, we need conscious people to be pulling up their sleeves and helping do the work, not just talking about what’s wrong.

Lindsey • Mar 27, 2018 at 11:07 pm

Excellent reporting on an important topic.

Anissa Ryland • Mar 26, 2018 at 4:43 pm

Thank you for tackling this complex issue.

Lisa Gooden • Mar 26, 2018 at 2:12 pm

Excellent article, great information. Thank you for your research and writing.

Cole T. • Mar 26, 2018 at 1:42 pm

The scars of segregation are here to stay for the foreseeable future. Neighborhoods are often drastically weighted for a certain race (In older ones anyway) while most people who do blue collar jobs are either immigrants or people of color. It disgusts me that the country I live in is still like this. The scars need to fade. They will eventually, but in my book, not soon enough.