Redundant at best

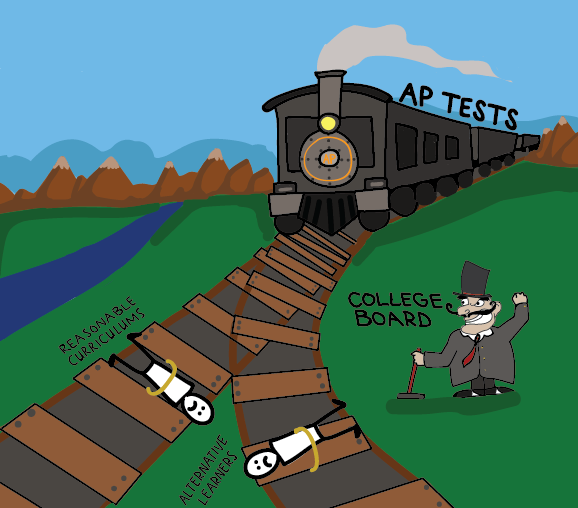

AP courses force students to learn tests not material

May 7, 2018

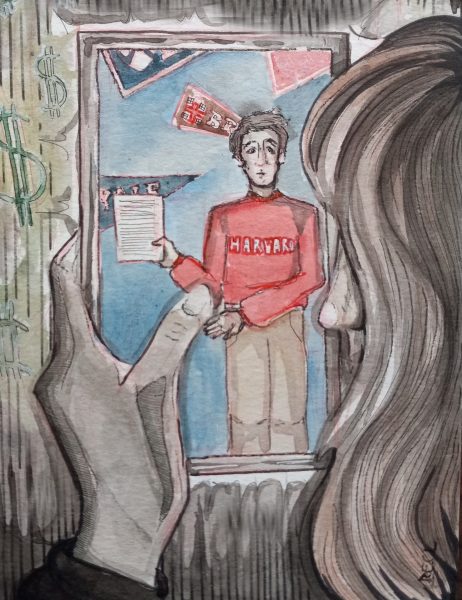

Sophomores to seniors around the school will all tell you AP exams are hell in a hand basket. And honestly who can blame them? Two weeks with back-to-back tests after long nights spent hunched over a textbook trying to memorize a unit’s worth of material from the first few weeks of school is not what I would consider a good time. But even considering all that stress over energy-sapping, soul-sucking tests, even after missing classes, the thing that bothers me the most about AP classes is that I feel like I spend the entire year learning how to take a test.

Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to criticize my teachers because I feel like we waste all of our time working from examples of past free-response questions. They’re just doing their job—which is to prepare me for the AP exam. But since when is it my teachers’ job to prepare me for a test instead of prepare me for life? Thanks, AP curriculum. I know how to detect satire in 1800s British prose, but I have never learned how to fill out a W-2 tax form.

Now, my complaints may come off whiny, so I’m going to paint a picture for you. Imagine a world without AP tests. Now ignore what that might mean in the college-credit picture and focus on the classroom part, the part where you come to school to learn. There is no April full of discussions about squeezing a few hours of literary analysis into the 40-minute time period, nor multiple-choice prep or short answers to write. You walk into class and have a discussion about a piece of poetry or spend all day in the library doing research about the economic effects of the French Revolution. I feel like if that were the case, I would have a much richer, more balanced education instead of dreading school from March until the beginning of May.

But we do not live in this perfect world. We live in a world where a good portion of students don’t even take the test after a year in an AP class because the $94 isn’t worth the likelihood they will fail the test. And in fact, your chances of passing are near 50/50, at least for AP U.S. History, according to the national 2017 College Board results. And your chances of getting a four or a five, which is what many colleges require for credit, are even slimmer. So what are you left with, after a year of hard work in an AP class? No college credit and a waste of $94, but hey, at least you can write an essay about the Stamp Act in 30 minutes.

Again, my frustration is not with the many wonderful teachers at McCallum, nor with the concept of getting college credit. My problem is that it seems like we spend a inordinate portion of the year learning how to pass the AP test, how to write the response question or how to manage the time constraint, and less time focusing on the material.

This “AP boot camp,” which occupies all of April, gets frustrating when my mental efforts have long since moved on from multiple-choice practice. But don’t confuse this sentiment with senioritis. It’s not that I’m lazy or have stopped caring about school. I do, however, want to learn and prepare myself for college life more than I want to practice writing essays.

Unfortunately, my complaints against the AP system aren’t really easily solved. The busy work done in class to prepare us for the AP tests is graded not optional. And while I acknowledge that they may be helpful to my score, I would prefer to spend outside-of-school time with AP prep so I can get the most out of my numbered remaining days of high school.

gracie ross • May 10, 2018 at 11:56 am

Really great story with a cool layout in the paper!!